Monday, January 19, 2015

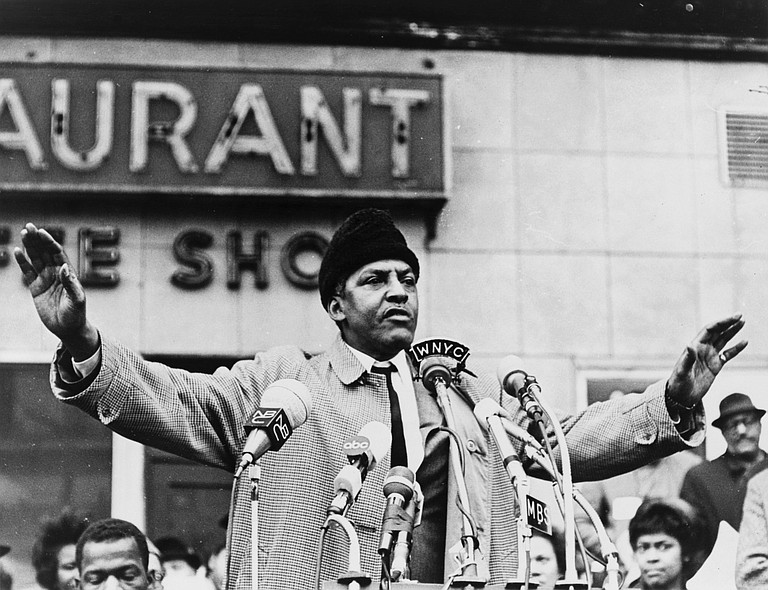

If Martin Luther King Jr. was the face and the voice of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and '60s, Bayard Rustin was the movement's conscience because he was Dr. King's conscience.

But John D'Emilio, a professor of history and gender and women's studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of "Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin," calls Rustin a man without a home in history.

"If Rustin has been lost in the shadows of history, it is at least in part because he was a gay man in an era when the stigma attached to this was unrelieved," D'Emilio writes in the book's introduction.

Rustin's sexuality, which he was always open about, was a point of friction even among champions of human rights for African Americans in the South during the Jim Crow era, including King. Rustin had grown up in eastern Pennsylvania with his grandparents, who were involved in anti-Jim Crow campaigns and active with the NAACP.

Because of the influence of his Quaker grandmother, Rustin became an ardent pacifist. As a Quaker, when Rustin's draft number was called during World War II, he had the option of serving in the Civilian Public Service rather than the infantry; Rustin instead cited his anti-war convictions and chose to go to prison, where he served more than two years, from 1944 to 1946.

In his lifetime, Rustin also participated in socialist politics as well as labor organizing. In 1956, Rustin traveled to Montgomery, Ala., to support and advise King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference in organizing a boycott of the public transit system. At the time, King had not adopted the views on non-violence for which he would later become famous. At the urging of Rustin, who had studied the teachings of Mohandas Ghandi, King stopped using armed bodyguards despite the firebombing of the Kings' home in early 1956.

Still, despite the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rustin's sexuality and former communist ties didn't sit right with movement mainstreamers, who deliberately kept Rustin out of the spotlight, at times even refusing to let Rustin speak at events he organized, including the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

"This march is of such importance that we must not put a person of his liabilities at the head," Roy Wilkins, leader of the NAACP, said of Rustin's involvement at the time.

Three years earlier, when Adam Clayton Powell Jr., an African American Democratic congressman from New York, learned that Rustin and King planned to protest the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, Powell threatened to spread a rumor that King and Rustin were lovers.

Because organizations would so often distance themselves from Rustin, and because Rustin always put movement work ahead of his personal feelings, he had the freedom to float around and latch on to campaigns in which he was interested.

As a result, Rustin was in and out of Mississippi and worked with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and MFDP's Fannie Lou Hamer, whom Rustin called the backbone of the movement in the Magnolia State.

Of Mississippi, Rustin once recounted in a 1979 interview: "I want to say that I don't think there were ever a more courageous group of young people. They knew that people were going to get brutalized and beaten. They knew that people might even get lynched."

Rustin died in 1987 at the age of 75. In 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the nation's highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID