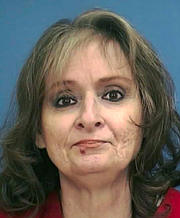

Ronni Mott's journalism and storytelling defined her—and none more than her work on physically and sexually abused, tortured and murdered women in Mississippi. File Photo by Trip Burns

Wednesday, March 17, 2021

I first got to know Ronni Mott in my writing classes, in 2006, I believe. Over the years I've taught a wide variety of students to be writers, and often journalists, but Ronni was special from the start. She had a deep desire to tell stories, and I've never met anyone with more of a burning fire in her belly for social and political justice, and equality, especially for women.

Then in the Jackson Free Press' longtime and rather crumbling Fondren offices, Ronni sat at a long table in what I called the railroad classroom—it was long and skinny—and soaked up every word and anecdote about narrative reporting and storytelling. She didn't start out to be a journalist; she was an accomplished artist in her earlier years; she owned a graphic-design firm in Washington, D.C.; and she ended up in Jackson doing marketing work in the ill-fated WorldCom that tumbled due to greed and corruption.

Ronni could have done something where she would make a whole lot more money than writing stories that made Mississippi uncomfortable with its prejudices and practices. But by then nearing 50, she wanted to make a difference. She was a natural writer, and when she started digging in and learning the craft of writing, revising and reporting, she became a force of nature. She especially delighted and excelled in shoe-leather reporting and face-to-face deep listening to people telling their stories, especially stories that desperately needed to be told.

Heather Spencer: Did She Have to Die?

Ronni Mott looks deeply at the failures that led to Heather Spencer's second vicious attack that killed her.

At the end of the writing class, Ronni asked to be an intern at the Jackson Free Press. Because she was older than I was, and due to her corporate background, I dubbed her the chief executive intern. From there, over a decade give or take, Ronni sped up the ladder becoming the managing editor, and later a freelance writer and editor for us. She had also improved her editing skills while learning to rewrite her own work to go from good to amazing—the last step too many potentially great writers skip.

But it was her own journalism that defined Ronni—and none more than her work on physically and sexually abused, tortured and murdered women in Mississippi. In her award-winning and human stories on domestic and interpersonal violence here, Ronni redefined how the issue should and can be written about in Mississippi, with pieces packed with evidence-based solutions, including how to stop abusers from abusing.

Put it this way: Ronni went far, far beyond the usual "why does she stay?" and "women abuse men, too, you know" narratives that usually truncate deep journalism on this issue in Mississippi and kept people ignorant about both the reasons and depth of the problem and what could be done about it.

Her work saved lives. This I know.

Avoiding 'Why Does She Stay?'

The Ronni story that comes immediately to mind to me is a piece I still use in writing classes: "Grant Me Justice: Two Women Killed in Two Weeks" about the vicious domestic murders of Doris Shavers and Heather Spencer. The story was a collaborative piece she led with another former writing student Candy Hagwood and me helping because we needed to get it out fast. But Ronni and Candy did the hard work, especially tracking down and visiting with the Shavers family right after losing Doris; I only added context from police reports about Spencer I had received from a source and helped tie the story together.

What was special to me about that particular story was Ronni's burning desire to show that the same violence happens across communities and divides—Heather's murderer was the white son of a prominent local family; Doris' killer was a Black ex-boyfriend in very different circumstances. And I assure you, they never asked grieving families the most ignorant question, "why does she stay?"

Ronni knew that you don't reduce violence against women, or sexual assault or stalking or trafficking, by starting a story with statistics or a sentence like "Mississippi is the most dangerous state for women!" even if it's true. You start it with humanity, and you begin with a story. This story began with the narrative of Doris Shavers' ex-boyfriend shooting her in the head while she braided her daughter's hair. You're there. You see it. As we all should.

Of course, this was one of many, many violence-against-women stories Ronni wrote for the Jackson Free Press, and she won multiple awards for them. Every year around the JFP Chick Ball, she and the Center for Violence Prevention would choose an angle that she would go in-depth on and that the Chick Ball would raise money to help alleviate or support.

But sometimes Ronni's reporting was focused on straight-up speaking truth to power, regardless of the political brand and even when other media turned away. And not everyone liked that.

'Excellent Work Is the Best Response'

It was in summer 2008 that Ronni and I learned that then-Gov. Haley Barbour had pardoned four men convicted of vicious murders of women, like Michael Graham who had driven up next to ex-wife Adrienne Klasky Graham at an intersection and shot her in the head with a 12-gauge shotgun at point-blank range.

We were tipped off that pardoning women-killers was a pattern for Barbour, and Ronni set out to confirm it. She (with help from then-interns Sophie McNeil and Maha Mohamed) started chasing down the details of the murders by a string of Barbour pardons of "trusty" white men (who, it turned out, served him and wife, Marsha Barbour, in the Governor's Mansion). The hardest part (this was before newspapers.com started easily spilling the historic tea) was finding the details of the murders of women; Ronni and her team called local newspapers in locations around the state, finding that a number of male editors weren't eager to talk about the stories.

Barbour Pardons 4 Brutal Killers of Women

Ronni Mott and a team of women interns investigated a list of pardons by Gov. Haley Barbour in 2008 of men who had brutally murdered wives and girlfriends.

But she got the information and published the details. Other Mississippi media outlets ignored the story of Barbour's pattern of pardons, as they were wont to do with the powerful lobbyist-turned-governor. It wasn't until four years later, at the end of his term when Barbour pardoned a shockingly long list of people that the media went a bit haywire over it, but without giving Ronni credit for her early work on it.

When she did the original work in 2008, Bob Herbert wrote about her work in his column in The New York Times with proper credit, as did Radley Balko, who has done great work about Mississippi issues, but from outside the state. But The Clarion-Ledger ran a column giving credit to Balko for Ronni's work, and blaming the whole "State" unfairly for Barbour's pardons decision. It was bizarre and disturbing to see this intentional disrespect of Ronni's enterprise work.

You really couldn't make it up: A "local" newspaper publishing a column by women giving credit for Ronni's work to a man elsewhere while not landing the blame for the pardons on the powerful Mississippi man who did it. That pretty much summed up the misogyny that Ronni and other JFP women have long drawn for daring to do this truth-telling work; a local blogger (supported by politicians' ad dollars) trashed Ronni over an intelligent opinion piece she wrote about the Obama stimulus plan: "Is Ronni Mott a liar, a hack or just plain stupid?" The post came up for years when you searched her name, although I see now just the headline remains in Google.

Michelle Byrom on Death Row: Ronni Mott's Investigation

Ronni Mott's investigation of Michelle Byrom's murder case helped free her from death row in Mississippi. Other media followed her viral coverage.

I assure you Ronni was none of those things—nor was she blinded by partisanship. One of her big stories was breaking and leading the coverage that eventually helped get Michelle Byrom, an abused woman accused of murdering her abusive husband, off death row. Ronni's work in 2014 not only provided human details about the abuse Byrom experienced, but also showed that evidence that could exonerate her was kept out of the trial. Democratic Attorney General Jim Hood did not want the outcome reversed, and Ronni's work challenged the narrative he kept pushing about Byrom.

Oh, and a prominent male journalist followed her work on Byrom and then was happy to collect credit for the work Ronni started. Rinse, repeat. But as a woman journalist in Mississippi, Ronni knew that you just have to keep calm and carry on.

Or to use a phrase we both believed in: "Excellent work is the best response." She was superb at following that one.

Bearing Witness About Father's Past

Ronni, who died on Feb. 2, 2021, of natural causes at age 64, had a vigorous life in Jackson, many friends and readers, and an important effect on journalism, especially about abused women. She was a social-justice warrior and, like many, worked too hard and too long—but that work means that her life mattered in ways that are hard to measure. She had taken on the position of editor-in-chief of the Vicksburg Daily News since 2019.

She was also a popular yoga teacher (especially with women more our age who can't twist and contort as the kids do), she loved cats and was funny with a deep, loud laugh, one I've now learned that she shared with her sister, Inga, whom I've been talking to and who has filled me in on her childhood. I knew, of course, that Ronni's family is Austrian, and their story is epic.

Beate Veronika Frisch was born in Germany in 1956 to a former soldier for Hitler's Third Reich, a fact she suddenly told me one day. Then, in 2009, she wrote about it, but in context of both Holocaust denial and glorification of the Confederacy and the Lost Cause, which I had watched her study and think about, including the legacies continuing in our state today.

"Suffice to say that he had little choice when drafted into the Third Reich," Ronni wrote of her father Franz A.P. Frisch. "He could join the resistance, putting his family in danger, or he could go into the army. To his lifelong regret, he chose the army, fighting in the trenches as a private, a rank he could not rise above because he could not prove his blood was 'pure.' Neither of my parents got the worst of it, though; neither were tattooed, intentionally starved or gassed to death."

Bearing Witness

Ronni Mott writes about her reckoning with her father's past fighting for Hitler in the Third Reich and the lessons for today.

By the time Ronni wrote about her father for the first time, she had thought it through in context of what she had seen in Mississippi.

"As the daughter of survivors from one of the history's most brutal regimes, I bear witness to the injustice of those events, as I do the injustice of white supremacy, the injustice of men who abuse their women and the injustice of poverty among so many others. Whatever color it is, whatever political stance it takes, at the root of intolerance for another human being is ignorance, fear and the need for control. Humans have a unique ability to dehumanize those we fear or those we wish to dominate."

Her father was captured in Italy and was held in an American POW camp for two years, an obituary explains. He provided intelligence on European shipbuilding technology before immigrating with his family to the U.S. in 1958. He later wrote a memoir about fighting on five fronts, and both he and his wife, Gertraud Schriener, died in Jackson after relocating here to spend their older years near Ronni. The couple's survivors were three daughters: Elisabeth M. Brandt, Inga Estes, and Beate Veronika Mott, whom we know in Jackson as Ronni.

Inga told me this week that their mother was a "serial entrepreneur, and an avid gardener who specialized in growing gorgeous, aromatic roses. I always thought that the hours she spent on her knees in her garden was her own private way of being grateful and celebrating being in America after surviving World War 2 in Europe."

Ronni, Inga told me, had a horse she adored as a young woman, and did extraordinary artwork—a talent later she put to the side when she decided to devote her skills and deep well of compassion and empathy to narrative storytelling.

The Mott Award for Daring Woman of the Year?

There are many things about Ronni Mott that I will never forget, from cocktails on press night at Pi Lounge in Fondren to yelling across the tiny newsroom as we were breaking stories—and a huge one is that she never wanted to stop learning or honing her own craft. She adored those writing classes and eventually became a co-instructor in them after she had given up the full-time intensity of being an editor, choosing instead to do freelance writing, editing and teach more yoga classes. She attended more of my classes than anyone ever has alongside both the general public and JFP staff members, and she knew the lessons by heart. But she was present each time like it was the first one she'd ever attended.

I have periodic thoughts of bringing back the Chick Ball—in perhaps an expanded form—when my current work of starting up a new publication normalizes a bit. In thinking about Ronni since learning of her death, I now would like to relaunch it in her honor when the time is right. Maybe there is a Mott Award for a daring woman of the year.

None of us are perfect people with flawless pasts or perfect predecessors shaping us, but Ronni was willing to face her and her family's history—and what I must believe were the demons within it—in service of a larger beloved community. I'll leave you with Ronni's own words from the piece about her father; may she continue to inspire Mississippians to always search and engage our better angels:

"History allows me to make sense of my world. When I understand the context of current eventstheir historical, political and economic frameworktheir content falls into place. History gives events the colors of my imagination, the flavors and emotions of the moment instead of the drab black and white of the printed page or the flat two dimensions of a photograph.

"To know and understand what came before means we can choose a different road. When I recognize ignorance, fear and intolerance in myself, I can recognize it in all of mankind. In the recognition lies compassion for all people and the path to peace.

"Remembering and honoring those who came before is simply part of the bargain."

You can join a virtual memorial to Ronni Mott's life Thursday, March 18, at 7 p.m. here. Her friends and roommate Allison Walker have organized an informal gathering in her honor at Fenian's in Jackson this Friday at 5 p.m. Fenian's has an outdoor space.

Email Donna Ladd at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter at @donnerkay.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID