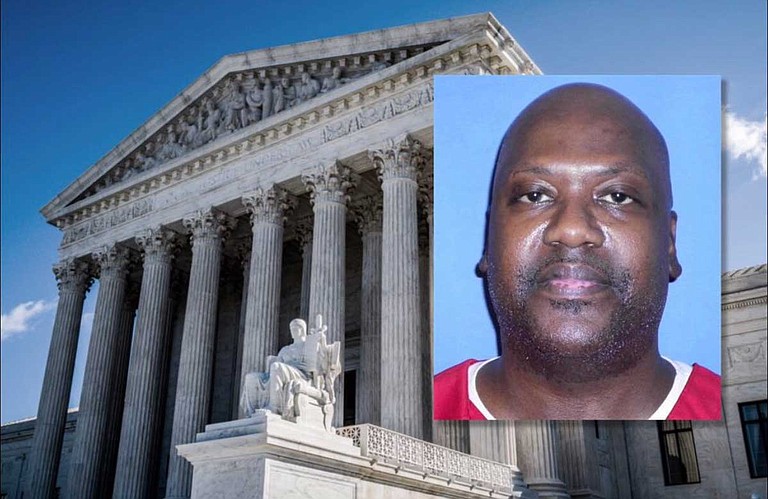

The U.S. Supreme Court has overturned the murder conviction of Curtis Flowers, an African American man whom prosecutors have tried six times for the same 1996 slayings of four people at a furniture store in Winona, Miss. Photo courtesy Phil Roeder (Creative Commons)/Mississippi Department of Corrections

Friday, June 21, 2019

The U.S. Supreme Court has overturned the murder conviction of Curtis Flowers, an African American man whom prosecutors have tried six times for the 1996 slayings of four people at a furniture store in Winona, Miss. The court found that prosecutors violated the Constitution by repeatedly blocking black jurors. Flowers has been locked up in Mississippi's Parchman prison for the past 22 years.

"We are grateful that the Supreme Court has reversed Curtis Flowers' conviction," said Flowers attorney Sheri Lynn Johnson in a Friday morning press statement. "Seven members of this court painstakingly analyzed the complex factual recorded and concluded that (State Prosecutor) Doug Evans discriminated on the basis of race in a decision that reaffirms the importance of racial fairness in the administration of justice, both for the defendant and for the community."

The nine-member court overturned the conviction in a 7-2 ruling, with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, a Donald Trump appointee, writing the majority opinion.

"The State's relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of black individuals strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury," Kavanaugh's ruling reads.

When retired Tardy Furniture employee Sam Jones arrived at work one July morning in 1996, he found the bodies of employees Robert Golden, Carmen Rigby and Derrick Stewart. He also found the body of Bertha Tardy, the owner of the store who had called him earlier that morning and asked him to come in to help train two new employees. Three victims were white, and one was black. All had been shot.

Police suspected Flowers because Tardy had fired him less than two weeks prior, and eyewitnesses claimed they saw him near the scene of a car burglary earlier that morning, where someone had stolen a .38-caliber pistol. Though investigators never found the weapon, they declared that the bullets at the scene were a match for a .38-caliber pistol.

The ruling relies on precedent set in the 1986 Batson v. Kentucky ruling, which found that prosecutors cannot use preemptory strikes against jurors on the basis of race. In Flowers' first four trials, prosecutors for the State tried to block all 36 black prospective jurors from the case.

The fifth trial consisted of nine white jurors and three black jurors, but there is no record of the racial makeup of prospective jurors in that case. The jury could not come to a decision.

In Flowers' sixth and most recent trial in June 2010, prosecutors for the State struck five of six black prospective jurors, resulting in a jury of 11 white jurors and one black juror. In Flowers' sixth trial, the state asked 145 questions of all five prospective black jurors, but just 12 questions of the 11 white prospective jurors. Disparate questioning motivated by race, Kavanaugh wrote, violates the U.S. Constitution.

"In sum, the State's pattern of striking black prospective jurors persisted from Flowers' first trial through Flowers' sixth trial," Kavanaugh wrote. "At the sixth trial, moreover, the State engaged in dramatically disparate questioning of black and white prospective jurors."

Justice Clarence Thomas, who is African American, wrote the dissent, which Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, joined.

Thomas' dissent accuses the other seven justices of ignoring the "race neutral reasons" the State gave for striking jurors in the sixth trial. Two jurors knew Flowers' family and had been sued by Tardy furniture, the family business of one of the victims and the site where the killings took place.

"One refused to consider the death penalty and apparently lied about working side-by-side with Flowers' sister," Thomas wrote. "One was related to Flowers and lied about her opinion of the death penalty to try to get out of jury duty. And one said that because she worked with two of Flowers' family members, she might favor him and would not consider only the evidence presented."

In Kavanaugh's decision, though, he cited at least one juror whom he believes attorneys struck based on race: Carolyn Wright. Prosecutors claimed they struck her because of her relationship to people involved in the case, but in Friday's ruling, the court noted that prosecutors did not similarly strike prospective white jurors who also had such relationships.

Thomas' dissent suggests that his fellow justices only took the case because of the media attention it had received, although he did not explain his reasoning.

The court did not make a judgment on Flowers' innocence. State prosecutors may still decide to try Flowers a seventh time.

"That Mr. Flowers has already endured six trials and more than two decades on death row is a travesty," Johnson, Flowers' attorney, said in the June 21 statement. "A seventh trial would be unprecedented, and completely unwarranted given both the flimsiness of the evidence against him and the long trail of misconduct that has kept him wrongfully incarcerated all these years."

Follow State Reporter Ashton Pittman on Twitter @ashtonpittman. Send tips to [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID