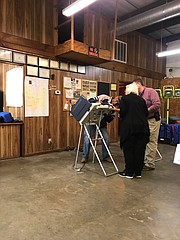

A polling location in Philadelphia, Miss., turned nearly a dozen people away from voting on Nov. 6, 2018, when two sites, one pictured above, had issues with machines. Photo by Ko Bragg

Tuesday, November 6, 2018

A polling location in Philadelphia, Miss., turned nearly a dozen people away from voting this morning because poll workers didn’t have enough back-up paper ballots after a snafu with voting machines.

Polling officials at the East Neshoba County Volunteer Fire Station plugged in the two voting machines at the site when polls opened at 7 a.m., only to find that the machines were registered for another polling location at Burnside Park, 13 miles across town. Poll workers estimated they only had about 20 paper ballots, all of which people had used by 7:30 a.m. Would-be voters pulled up in pick-up trucks and sedans only to have officials ask them to come back later.

“We’re out of ballots,” poll worker Laymon Calloway said to voters this morning. “We’re having to do paper ballots, and they’re not here right now. Please come back before 7 p.m.”

A single sheet of paper was taped to the wood-paneled wall near the entrance of the precinct. It is Calloway’s “Certificate of Completion” from the Mississippi Secretary of State’s office, stating that he had finished all requirements for the online poll-worker training course on Oct. 3.

“To me that’s a travesty to the electorate,” Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann told the Jackson Free Press today. "We have trained everyone, election commissioners and circuit clerks on opening the precinct at 7 o’clock, and we have trained everyone to bring emergency ballots in case something happens. We emphasized that again yesterday afternoon. Why an election commissioner in Neshoba County didn’t do that, I can’t tell you. That’s why they got elected. Next time they're up for election, you remember that.”

‘We Used to Order a Lot of Ballots’

By 8:12 a.m., a poll worker announced that Neshoba County Election Commissioner Yvonne Moore was at Bobby’s Country Store, five miles away with about 100 paper ballots.

“We used to order a lot of ballots, and we didn’t use them,” Yvonne Moore said later. "It was just an honest mistake.”

Almost every single person among the dozen who could not vote this morning promised they would come back later in the day.

Only two black women decided to wait for the quaint polling site to get it together. One of them was Kenya Beckwith, who sat in a metal folding chair until paper ballots arrived.

“It’s important to vote,” she told the Jackson Free Press after she submitted her ballot. She said she stayed because she has “the privilege of having an employer who also values the right to vote.”

A local pastor showed up around 8 a.m. to vote, too. But once he realized he wouldn’t be able to vote, he left—but not before saying something under his breath.

“Hmm. It’s a lot of trickery going on. I’ll see you later,” he said. He did, in fact, at a gas station that afternoon after picking up his daughter from school. He asked if everything was up and running by then. It was.

The county’s circuit clerk, Patti Duncan Lee, who is the go-to person to repair technological glitches, had to assist with court this morning, so other county officials had to pick up the slack to fix the issue. Jeff Mayo, the Neshoba County administrator, showed up to the fire station to take cards out of the machines to swap with the Burnside location. He came back to the fire station at 8:31 a.m. only to realize that he was missing another piece of equipment.

So he had to go back to Burnside again.

Memories of Mt. Zion and Three Civil Rights Workers

By 9:17 a.m., a group of women who attend church at nearby Mt. Zion United Methodist Church pulled up. White supremacists burned the church in 1964 after Freedom Summer volunteers identified it as a voter education site. Volunteers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman came back to investigate the burning on Father’s Day that year. On their way back to the Congress of Racial Equality office in Meridian, Miss., Sheriff’s Deputy Cecil Price pulled the men over and said they were speeding. He then took them to the jail in town. The Klan and other members of law enforcement planned their execution as they held the trio in jail.

The sheriff’s department released the men, but quickly recaptured them, tortured them and buried them in an earthen dam. Some believe at least one of them was castrated and buried alive.

Their murders launched an FBI investigation that spanned 44 days, and largely helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Congress passed the Voting Rights Act a year later, but it took until 2005 for justice to prevail when a Neshoba County jury found Klansman Edgar Ray Killen guilty of three counts of manslaughter. He died at Parchman, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, at the beginning of 2018 at age 92. He had been serving a 60-year sentence for his role in planning the ambush and murders.

Killen helped found the Klan in the Philadelphia, Miss., area and was its chief recruiter, which the Ku Klux Klan called a “kleagle.” He had been among 18 men tried in 1967 on federal charges of conspiring to violate the civil rights of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, but was acquitted even as seven others were convicted and served several years.

As the Mt. Zion women swung their legs out of the car, Mayo pulled up in his white Ford F-150 after about 50 miles of round-trip driving. He hopped out and beat the women into the precinct.

Five minutes later, machines finally in order, two of the women from the Mt. Zion congregation were the first people of the day to cast electronic ballots—two and a half hours after the polls opened in Mississippi.

The mother in the group hadn’t even realized the controversy that had ensued before she selected her candidates of choice on the e-machine. But, once she got wind of it, she shook her head.

“That’s the way it goes,” she said.

Email city reporter Ko Bragg at [email protected]. Philadelphia, Miss., is her adopted hometown.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID