Kitsaa Stevens, who coordinates events at Jefferson Davis’s last home, Beauvoir, filed the initial paperwork for Ballot Initiative 54, a petition to keep the 1894 state flag, which she believes is a symbol of reconciliation, not race division. Photo by Arielle Dreher.

Wednesday, September 9, 2015

By the time an aging Jefferson Davis moved into a borrowed cottage on the Beauvoir plantation near Biloxi with a gorgeous view of the Gulf of Mexico, his own life had mirrored the rise, fall and disappointment of the Confederacy. In a storied life, the Kentucky native had helped lead two nations, including one against the other; had owned hundreds of slaves before being forced to let them go; and had been indicted and put into solitary confinement for treason.

After Davis' release from prison in Virginia in 1867 for his role in the South's insurrection against the U.S. government, he faced a very different reality from his earlier life as the owner of several plantations and thousands of acres in Mississippi and Louisiana. By then, it was the short-lived era of Reconstruction in a war-torn nation, and Confederate leaders no longer had the benefit of the wealth and prestige they had enjoyed due to their dedication to a slave-driven economy across the United States.

The South was, for a few years, under control of the victors of the war—the Republicans (originally Free-Soilers) who had brought freedom to African Americans during the war. Freedmen were enjoying equality for the first time in the history of the nation. Davis' adopted state of Mississippi was even electing black officials to statewide office for the only time in its history, before or since Reconstruction, including two U.S. senators.

During that era when the tables were briefly turned against the former Confederate states, Davis was unemployed with a wife and four children and bounced around Canada and England before landing a job in 1869 as president of a Memphis life-insurance company. But, like that of the former Confederates states, Davis' luck improved in 1876, the same year that was the beginning of the end of Reconstruction.

It was a pivotal time in post-Civil War twists and turns; southern Dixiecrats wanted to return to a time when black people were subjugated rather than being equal or even in charge, and the tools to do it were a mixture of terror and politics. Radicals calling themselves "Redeemers" devised strategies such as "the Mississippi Plan" of 1875 to overthrow the Republicans in office in the South by threats and violence when necessary.

By the mid-1870s, and while evoking the symbols of the failed Confederacy, heavily armed and well-financed vigilante groups such as the White League birthed in Louisiana and the Red Shirts in Mississippi followed the lead of the Ku Klux Klan and openly started harassing Republicans serving or running for office, and threatening and even murdering both black freedmen and the whites who supported their freedom.

The threats and violence set the stage for federal capitulation to the southern planter elite in the Compromise of 1877 to resolve the disputed presidential election. To get southern lawmakers to agree to Rutherford B. Hayes' win over Democrat Samuel Tilden, Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction and allowing the South to begin a century of Jim Crow laws and Black Codes that blocked black southerners from voting, attending integrated schools, race-mixing or using public facilities until the 1960s.

The compromise allowed the North and South to reconcile as a nation, but brought anything but reconciliation to the races in the South, returning life for blacks as close as possible to slavery times, but without being owned outright by whites. "The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery," W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in his 1935 book, "Black Reconstruction in America."

Jefferson Davis' fortunes tracked with those of the southern states when an admirer offered him the use of Beauvoir to write his two-volume memoir of his four years as the president of the Confederate States of America with CSA's stated goals of maintaining and extending slavery into new states and guaranteeing that their runaway slaves were returned. Sarah Ellis Dorsey, a novelist from a slave-holding family in Natchez and her husband, Samuel Worthington Dorsey of Maryland, had owned several plantations and many slaves, including Beauvoir. A widow by 1876, she invited Davis to live on her plantation, then willed her capital and property to him when she died in 1878.

In the Beauvoir cottage, Davis told his story about the Confederacy in the two-volume "The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government." A U.S. senator from Mississippi in the lead-up to the Civil War, Davis had opposed secession, correctly predicting "troubles and thorns innumerable." But even 14 years after federal troops had helped 137 of Davis' slaves escape from his Brierfield plantation near Vicksburg in 1863, the former CSA president still defended the institution of slavery, which his state's 1861 Declaration of Secession had identified as its reason for leaving the United States.

In volume 2, Davis even compared the North to a biblical serpent tempting enslaved black people—whom he called "several millions of human beings of an inferior race—peaceful, contented laborers in their sphere"—to rebel against an institution that had improved their lot.

"Generally they were born the slaves of barbarian masters, untaught in all the useful arts and occupations, reared in heathen darkness, they were transferred to shores enlightened by the rays of Christianity," Davis wrote. "... Never was there happier dependence of labor and capitol on each other. The tempter came, like the serpent in Eden, and decoyed them with the magic word 'freedom.'"

No Mention of Slavery

A century and a half after the South surrendered, Kitsaa Stevens coordinates events for the 52-acre Beauvoir, now a private museum. "The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library" includes the original Davis home, a cemetery of Confederate veterans—it was used as a veterans' home for Confederate soldiers and their families until 1957—and a replica of Davis' writing cottage built Hurricane Katrina destroyed the original one 10 years ago.

Originally a volunteer who became an employee of the museum and grounds in 2014, Stevens organizes popular gatherings there including "Arts and Crafts Under the Oaks" and "View the Cruise at Beauvoir," an antique car show sponsored by the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a controversial neo-Confederate group, that has owned Beauvoir since 1902 when it opened as a Confederate veterans home. Beauvoir became a nonprofit museum and library in 1957, once the veterans and their families were gone, Stevens said.

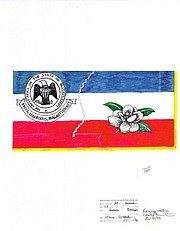

Stevens, 55, is also arguably one of the more passionate defenders of the current Mississippi state flag, which has included the most notorious Confederate battle emblem in its canton since 1894. This summer, in the wake of a renewed movement to retire the current flag— the only one in the nation that still overtly celebrates the Confederacy—Stevens filed the initial paperwork for Ballot Initiative 54, which proposes an amendment to Mississippi's Constitution that would make the current flag, adopted in 1894, the permanent state flag.

Stevens said her employers, the Sons of Confederate Veterans organization, did not ask her to file the petition, but they support her decision to do so.

Beauvoir administrator Greg Stewart was active in the 2001 campaign to keep the 1894 state flag and spoke about his experience in a June CNN interview. The Southern Poverty Law Center listed Stewart's involvement with an organization called Free Mississippi that formed back in 2000 to keep the 1894 state flag. SPLC called Free Mississippi a hate group back in 2001, but it is not currently listed because they have not been active in several years. Free Mississippi's Facebook page, however, indicates that it is still actively campaigning to keep the state flag, although the contact information on the website is out-of-date.

Mark Potok, senior fellow at SPLC, said that the center has never listed the Sons of Confederate Veterans as a hate group because it doesn't have an officially racist program. The Mississippi chapter, however, is "quite a bit more radical" compared to other states, Potok said. In 2011, the Mississippi chapter asked the state for a commemorative license plate that would include the portrait of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a slave-master millionaire before becoming a Confederate general and the first national leader of the Klu Klux Klan. The license plate was not approved.

Reconciling Slavery

The state flag, Stevens argues, was adopted as a "reconciliation" symbol, merging the memory of Civil War battles with the red, white and blue of the American flag. "Our flag represents a reconciliation of that struggle—that we are working as a common entity to move forward," she said.

Stevens said she has learned this history of reconciliation since she started working at the Confederate museum last year. She said she understands the viewpoint of African Americans who reject the flag because it symbolizes a war fought over slavery, but believes that we should not just keep the parts of history around that make people happy. A lot of people will not visit Beauvoir, she said, because they think it promotes slavery, but she emphasized that slavery, including the hundreds of slaves Davis and his brother owned, is not mentioned anywhere on Beauvoir's tour—primarily because by the time Jefferson Davis got to the coast, the Civil War was over so Davis did not own slaves when he got to Beauvoir.

Slavery is, however, discussed in great detail in Civil War revisionist books sold in Beauvoir's Stars and Bars Gift Shop. They include "Was Jefferson Davis Right?" by brothers James Ronald Kennedy and Walter Donald Kennedy of Copiah County, who also wrote "The South Was Right!." The books demonize abolitionists and argue, like Davis, that enslaved Africans were well-treated and happy with their situation.

Slavery, Stevens admitted, isn't talked about enough in discussions about the Civil War, but she is adamant that the flag is a positive symbol of reconciliation that Mississippi state leaders declared it to be in 1894. That year is so important to her thesis that she has filed a lawsuit in Hinds County Circuit Court asking a judge to rewrite the title of her initiative to refer to the flag as "the 1894 flag." The current initiative ballot title wording asks to keep "the current state flag." Since the initiative likely would not go onto the ballot until 2018, the next time state elections are held, Stevens wanted to make sure that the initiative represented the state flag adopted in 1894 in case the flag changed before then.

Once the title dispute is over and an official title is set, Stevens will have to collect more than 107,000 signatures of registered voters to get it on the ballot.

The Magnolia State Heritage Campaign and the Coalition to Save the State Flag are the primary organizations that will help to collect signatures once Stevens' initiative is finalized. Arthur Randallson, the director of the Magnolia State Heritage Campaign, said the two organizations will work with local Tea Party chapters and smaller community groups to garner support for Initiative 54.

Stevens admits that her preferred "reconciliation" flag may lose, though.

"The bottom line is, if the majority votes to change our flag, that's OK because we live in America, and this is a democracy, and that's what the people say," she said.

'Put It In Your Attics'

Talking about slavery may be taboo inside Beauvoir, but one room is entirely dedicated to the Civil War, with a row of secessionist flags covering one wall. Mississippi's secession flag contained a white star on a blue background in the canton, a magnolia tree in the center and a red stripe at the end. The flag was adopted in 1861, when Mississippi's Declaration of Secession declared in its second sentence the reason the state was leaving the U.S. to join the Confederacy: "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world."

Dennie Spence, the head librarian and curator at Beauvoir, is quick to distinguish between the Confederate emblem in the current state flag and the one that flew over Mississippi when the Civil War began. In fact, he said, the federal government banned most secession-era flags when the Civil War ended in 1865 with the exception of Texas and Virginia. That included Mississippi's Magnolia flag, and a Beauvoir flyer states that the first act of the 1865 Reconstruction government was to remove it.

Another wall is dedicated to the progression and explanation of the flags of the Confederacy. Spence explained that the original "Stars and Bars" is often mistook for the battle flag that rests in the canton of the Mississippi state flag, which was never the official flag of the Confederate government.

The "rebel flag" was used in the canton of two iterations of the flag, but it was actually the battle flag of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, used to differentiate the Confederate troops from Union troops, Spence said. It gained favor in the South as the primary battle flag of Gen. Robert E. Lee in northern Virginia, and three well-known Mississippi brigades fought under it, led by Brig. Gen. William Barksdale, Gen. Carnot Posey and Jefferson Davis.

Because Lee's campaigns were the most successful for the South in the Civil War, the Beauregard flag was seen as a symbol of success for those Mississippi brigades coming home, Spence said. "If you're trying to remember any war, you are going to remember the best of it," he said. "Certainly, the Confederate army with the most success would be Robert E. Lee's in Virginia."

Lee himself likely would not approve of the fight to keep the Beauregard flag flying over Mississippi. His papers show that he was humbled and tortured by the loss of life in the Confederacy and was in little mood to keep celebrating the "lost cause" beyond the end of the way. He discouraged further use of the Beauregard flag that he fought under, advising his followers at war's end to "stow it away. Put it in your attics.'"

The general who led so many Confederate soldiers into battle also would not attend public gatherings celebrating the war, preferring that southerners focus on the reconciliation of the nation rather than dwelling in the past. "I think it wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered," Lee wrote in an 1869 letter declining a ceremony commemorating the battle at Gettysburg.

Back to White Supremacy

But to a South still angry about the loss of the war, not to mention the human property that produced most of its wealth, romantic symbols of the Confederacy remained important, as did a system of white supremacy. Drafters of the Mississippi Constitution of 1890 took advantage of the new freedom the end of Reconstruction gave them, and inserted language that make it near-impossible for freed blacks to register to vote, own firearms or continue to participate in democracy in any way.

"The Mississippi Constitution (that the 1894 flag was adopted into) legalized segregation, and it became the model," said Susan Glisson, a historian and the executive director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi.

Although slavery was gone, Glisson said, white supremacy lived on in the political sphere—and not just in Mississippi. Glisson pointed out that the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, that legalized segregation on a "separate but equal" basis, came down in 1896 from the U.S. Supreme Court. Starting right then, white supremacy replaced slavery as a way to suppress African Americans, Glisson said, and white-supremacist groups immediately started embracing symbols of the failed Confederacy to indicate their bias and supremacy over African Americans.

In 1894, the state decided to adopt a new Mississippi flag, which the U.S. Congress had to approve. The state chose a flag that incorporated the symbol Lee wanted mothballed, pointedly calling it a "reconciliation flag," which at the time was not about race relations, but about reconciling the nation in a way that pleased the South.

Congress approved the design.

The Beauvoir curator says the "reconciliation flag" is all about celebrating military prowess, not the white supremacy the Confederates fought to preserve.

"You can't look at it and escape Mississippi's military past," Spence said.

The battle flag in the canton, Spence insisted, never alone served as a Confederate flag on a national level. Actually, the battle flag indeed was used in the canton of the last two iterations of the Confederate flag, however, and the 1894 Mississippi state flag resembles the last flag the Confederacy used.

Senators at the time, Spence said, came up with the 1894 flag, likely those who helped draft the 1890 Mississippi Constitution who, he believes, in "their own strange ways pushed for reconciliation."

Gov. John Marshall Stone, a Confederate colonel, signed an order approving the flag, which historians believe was designed by Sen. E.N. Scudder of Mayersville. His daughter, Fayssoux Scudder Corneil, told the Mississippi chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1924: "My father loved the memory of the valor and courage of those brave men who wore the grey.... He told me that it was a simple matter for him to design the flag because he wanted to perpetuate in a legal and lasting way that dear battle flag under which so many of our people had so gloriously fought."

'Using Race to Push That'

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof executed nine African Americans inside the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., after they invited him in to share their worship service He was arrested and indicted for their murders, which authorities consider a hate crime, and is facing the death penalty.

Roof's online history revealed his identification with white supremacist groups, such as staunch Confederate flag and "white rights" defenders, the Council of Conservative Citizens, which grew out of the Citizens Council that started in Mississippi in the 1950s to fight integration. A picture of Roof surfaced featuring the 1894 Beauregard flag sewn to his leather jacket—the same Confederate flag that still officially flew in front of South Carolina's Capitol. Almost immediately, an emotional campaign began nationally to remove government-funded displays of the Confederate flag.

Once South Carolina legislators of both parties voted to take the flag down national attention shifted to Mississippi, the only state with a flag containing a blatant Confederate symbol, reviving a debate that had largely subsided since Mississippi voters chose to keep the 1894 flying in 2001.

Several Mississippians staked out sides on the debate early—politicians came out for or against bringing down the flag, and some punted by saying it should be up to the voters. Mississippi House of Representatives Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, drew the most attention when he cited his Christian faith as the reason to change the flag. Gunn is a leader in his Baptist church.

Russell Moore, the president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, wrote a widely read column saying that as a Christian, specifically a white Christian, it is important to understand why African American neighbors would find the Confederate symbol so objectionable. Besides the flag representing an army that fought to keep slavery, hate groups who opposed civil rights have used it more recently, Moore wrote.

Moore, a Mississippi native, lives in Tennessee for his position, and said he would fly a huge Mississippi state flag outside his home if it was seen as a welcoming flag to everyone. He said the state flag does not give the correct perception about his home state.

"I find some of the best examples of racial reconciliation happening in the country in Mississippi," Moore said. "So Mississippi is not the caricature that many in other parts of the country would have it."

The Southern Baptist Convention itself supported slavery in the 1800s, as well as segregation in the church—specifically, the group formed after a split from the northern Baptists who opposed slavery. "That was a repudiation about what the Bible teaches from the gospel of Jesus Christ," Moore said. "So as time moved on, southern Baptists repented of that accommodation to that culture that was wrong and wicked."

The Southern Baptist Convention issued an apology in 1995 for its historic role in supporting "acts of evil such as slavery from which we continue to reap a bitter harvest, and we recognize that the racism which yet plagues our culture today is inextricably tied to the past...."

Still, despite such powerful statements in favor of changing the flag, Gov. Phil Bryant, a Republican with strong Tea Party support, said he would not call a special session to address the potential shift in public opinion, saying that Mississippians had already voted to keep the flag back in 2001.

Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves said it should be up to voters, but invoked the loaded images of "outside agitators" and "carpetbaggers" used against opponents of segregation and slavery in the state's past. "If the citizens of our state want to revisit that decision, and I am sure at some point we may, it will best be decided by the people of Mississippi, not by outsiders or media elites or politicians in a back room," Reeves said in a statement.

But political hesitancy to take a stand hasn't stopped determined Mississippians, black and white, from lobbying either to change the flag or leave it alone.

Rafael Sanchez began an online petition to keep the flag almost immediately after the Charleston shootings. It now has over 13,000 signatures. The Hattiesburg native said it's wrong to use the Charleston tragedy as a platform for bringing the flag down.

"Before (Charleston), nobody had an issue with (the flag)," he said. "That was my main reason for starting (the petition)."

Sanchez said his petition is not racially motivated and does not promote hate. He said what happened in South Carolina is tragic, but does not justify changing the flag. "I think it's a political maneuver by left-wing Democrats to gain more votes on their side, as well as (some conservatives)," he said.

The country hasn't been this racially divided in over 20 years, Sanchez said, but he does not view the state flag as a racial issue. "I think politicians are playing people against each other in order to gain more votes," he said. "They are using race to push that."

Real History This Time

When Ronnie Musgrove, a Democrat, became the governor of Mississippi in 2000, the state did not have an official flag. The state flag had not been re-codified since 1906 when it was repealed due to a legal technicality, and the Mississippi Constitution had not re-established it as the official state flag since then. In 2001, this was brought to the attention of the state, and Musgrove had to file an executive order codifying the current state flag while he figured out if the Legislature would want to approve a new design.

"It happened overnight," he told the Jackson Free Press last week.

There was a standoff in the Legislature over changing the design, however, and the core bipartisan leadership refused to adopt a new flag on their own—which many considered political suicide in a state that still could not muster the votes to elect an African American to statewide office over a century after the heady days of Reconstruction abruptly ended.

So Musgrove created a commission that would make a recommendation on the state flag. Its members decided that to adopt a new flag, a referendum vote of the people would be necessary.

Many 1894 flag opponents touted the flag as bad for business to gain support, avoiding talk about the reason Mississippi entered the war—to preserve and expand slavery—or the flag's continued use as a white-supremacist symbol. Regardless of attempts to downplay the controversy, the flag was a highly charged, politicized issue. Musgrove, along with the governors of South Carolina and Georgia, were all attempting to change their flags, and all three of them had it used against them, Musgrove said.

"The (candidates) coming in were campaigning against changing the flag," Musgrove said. "I knew it was going to be used against me, but some things are more important." Indeed, Gov. Haley Barbour attacked Musgrove for supporting a new flag in his successful campaign to unseat him.

A new effort will face similar challenges, Musgrove said, adding that it will take strong leadership to change the Mississippi state flag. He said a bill will never get to Gov. Bryant unless he publicly supports it, and while Gunn's support was influential, the governor and lieutenant governor will have to support a change for it to become a reality, he said.

"Changing our state flag won't solve all the problems of inequality in America," he said. "But not addressing something like our flag says we aren't even willing to try.

Former Gov. William Winter, a former segregationist now known for outspoken racial-reconciliation efforts, said the people of Mississippi were not ready to change the flag in 2001, but he thinks enough time has passed to change the public sentiment.

Winter said a flag that creates division and does not properly reflect the unity of Mississippi as a people in 2015 needs to go.

"Things like this take a long time, and there is more understanding of the issue (now) than there was 15 years ago," he said. "I think the time has come and the people of Mississippi are ready."

Some believe that the 2001 referendum was too rushed and unfocused on real issues to be effective. In 2001, business leaders felt it would be a better tactic to talk about the economic consequences of keeping the flag rather than address its connections to racism and human pain—a strategy that failed.

Glisson, of the Winter Institute, was a part of the effort then to replace the flag. She said the new flag needed to have meaning for people in order for them to vote for it—but her advice did not carry much weight then. "I suggested that instead of rushing to have a vote that we take the time to educate people about the history of the flag," she said.

Such a full embrace of history would no longer leave out facts about slavery while claiming that the flag is only used to celebrate the memory of fallen troops such as the student soldiers of the University Greys, all of whom perished in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg. Glisson understands the complicated relationship Mississippians have with the battle flag, but the harsh reality is that it was the flag of an army devoted to preserving slavery—something that does not represent the people of Mississippi anymore.

Dan Jones, who is on leave as chancellor at the University of Mississippi and does not speak for the university, remembers growing up in the 1950s and '60s in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Then, he saw groups use the Confederate symbol to express hate and their desire to remain a segregated society. "That was our (generation's) big exposure to the Confederate flag, and that carries over to today," Jones said.

It's more than just the tragic events in Charleston that have raised the consciousness of many people today, Jones said. A broad conversation in society about symbols associated with slavery, segregation and injustice toward black Americans has come to the surface in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and electing a black president for the first time, he said.

Jones said this is a different era than when he grew up in Warren County, and the flag should change because it helps damage human relationships and make people feel unwelcome or hated by people who support the flag. A state flag should indicate that all are welcome in Mississippi, he said.

Now, Glisson said, communities are showing their own interest in changing the state flag without the Legislature's involvement. Cities including Jackson, Oxford and Greenwood have decided not to fly the flag, although the majority-black state capital cannot stop the plethora of state offices from flying it. "While the Legislature avoids dealing with this issue, local people are taking it upon themselves to change things," Glisson said.

'Everybody Was Complicit'

People working to change the flag aren't avoiding its real history this time around. Jennifer "Bingo" Gunter, a Jackson native (and the first assistant editor of the Jackson Free Press), began a petition through moveon.org immediately following the Charleston shooting. Gunter is finishing her Ph.D. in southern history at the University of South Carolina. Like many expatriates, she still identifies as a Mississippi native to the core.

"I love my home state even with all its problems," she said recently.

Gunter, who is white, wants the full truth told this time around, with all its warts and discomfort. "We're still fighting about what the Civil War was about—it's frustrating," she said. "Slavery was bad, we all did it, and everybody was complicit," she says of white Americans.

So far, Gunter's petition has gained the most public traction with more than 66,000 signatures, the majority of which Gunter believes are Mississippi citizens.

Gunter is hoping to turn that support into a physical petition that can be signed and turned in to the secretary of state's office to counter a keep-the-flag effort such as Kitsaa Stevens' initiative. She hopes that one umbrella organization will get organized by December to lead the effort before the Legislature reconvenes in January.

Duvalier Malone, an African American, launched another online petition to bring down the state flag on change.org. Malone is from Fayette, Miss., and he now runs his own company in Washington, D.C., specializing in policy, advocacy and economic development—primarily in Mississippi.

Malone's inspiration and primary motivation for bringing the flag down comes from his grandmother.

"It was not about the petitions to keep the state flag," he said. "It reminded me why my grandmother was so nervous every time the Mississippi flag was raised."

Malone said the black community in Mississippi needs to be engaged with this issue to bring about change. He believes the community did not come out and vote in 2001, leading to the narrative that persists today in some politician's rhetoric: "We already voted on that."

"What I want to do is challenge those African Americans in the community to begin to sign petitions and tell our lawmakers that we must get rid of this flag," he said.

Malone's petition has more than 6,000 signatures so far, and he is planning a rally for late December or early January when the Legislature returns. Malone said he is focused on the bigger picture as well as history. Taking down the flag is also better for economic development, he said.

"We are at risk of losing economic development because (companies) don't want to be represented by that flag," he said. "It's more than just the hatred; our state (should be) represented with love and hospitality."

The question, of course, is how to make that change, especially since the state is largely led by white men who fear the loss of voters who still value the 1894 flag.

The law or the state constitution would need to change in order to take down (or permanently keep) the current flag. A member of the Mississippi House or the Senate could introduce a bill as early as January to change the flag. If the bill passes both the House and the Senate, the governor would then either sign it into law or veto it. The Senate and House could vote to override the governor if he vetoes the bill as well.

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, said he expects that a bill will be introduced when the new session of the Legislature convenes. He said such a bill would likely and logically suggest an alternative to the current flag.

The Legislature then could get the citizens involved in the decision-making process, like they did in 2001, in several ways. They could again put it on a ballot to change the law. Depending on the timing, they could also put a proposed constitutional change on a ballot. Citizen-driven ballot initiatives to change the constitution, like Stevens' effort to prevent changes to the flag, will be on the statewide 2018 ballot, while a Legislature-ordered referendum would happen quicker.

Winter said the Legislature ought to make the change itself, without involving the citizens this time. "I think the Legislature is in a position politically to make this change without harm to themselves from a political standpoint," he said.

A New 'Southern Strategy'

Back in 1993, Charles Milton wrote an editorial titled "Changing flag is a start." Milton, an Indianola native, wrote, "The great flag of Mississippi should be modified to represent the advancement of our state, and the voice of all who work so diligently for her future." The Enterprise-Tocsin in Sunflower County published his op-ed in 1993 and republished it recently at the start of July.

Milton, a black firefighter in Greenville, said his passion motivates him to push for the change. His love for the state and its hospitable people drove him to write the article. As a janitor in a local school in 1993, Milton had an honest conversation with a teacher about how his opinions mattered and that he could inform and teach people, driving him to put pen to paper.

Twenty-two years later, Milton's article now means more in the midst of the state's flag debate. Milton said he is not asking for people to stop flying Confederate flags off the back of their trucks if they want to, which he said he's seen more of in the past two months than normally. That's their right, and it's different from the government flying the battle flag on the entire state's behalf.

"Your heart will never change (if you're pro-flag), but at least people won't be afraid to come to Mississippi," he said.

As an art major, Milton designed a new flag, influenced by the current state flag's colors and the warmth of Mississippi residents. "If (changing the state flag) would be a start, to get people to start talking and stop assuming ... that is what I am about," he said.

Laurin Stennis was born and raised in Jackson and moved back home from Birmingham two years ago. After buying her house, the artist wanted to put up a state flag to show her pride. But she could not and would not fly the 1894 flag. Stennis said it holds loaded imagery that highlights the most negative parts of Mississippi history, and that a state flag should include history and hope. In 2013, frustrated that the state flag had not yet changed, Stennis designed her own. It sat in her drawer for two years—until the tragedy in Charleston.

Stennis, a block print artist, has since mailed her flag design and her story to politicians and city leaders who have voiced support for bringing down the flag.

The artist, who is white, had ancestors who fought for the Confederacy and owned slaves—and later worked to keep white supremacy in place. Her grandfather was long-time U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis, who signed the Southern Manifesto in 1956 opposing integration of public spaces, and did not vote for civil-rights legislation until 1982.

John Stennis became a Democratic U.S. senator in 1947, back when that party stood squarely for segregation, and the Republican Party was still closer to Abraham Lincoln's Free Soil Party that formed to oppose the expansion of slavery into emerging states and that, eventually, did free the slaves during the Civil War.

That stellar GOP legacy would end, or at least hit pause, after Democrats embraced federal civil-rights legislation in the 1960s, leading Republicans to embrace a "southern strategy" of reversing the party's history of embracing racial equality and reconciliation to appeal to southern Dixiecrats, who suddenly didn't have a party to back them.

Now, Stennis' family has evolved, and the granddaughter wants her story to show other white Mississippians that it's OK to have different views than your ancestors.

"It is possible to disagree with what some of your forefathers fought for without dishonoring their bravery," Laurin Stennis said. "It's not necessarily honoring them to harbor those beliefs and essentially shackle yourself to them."

Donna Ladd contributed to this story. Comment at jfp.ms/slavery. See flag designs proposed by JFP readers at jfp.ms/msflagdiy.

Alt.Flag Gallery

To view many more potential Mississippi state flag designs submitted by readers visit jfp.ms/msflagdiy. Submit your own designs (fun and serious) to [email protected], or post them on Instagram or Twitter using the hashtag #msflagdiy.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID