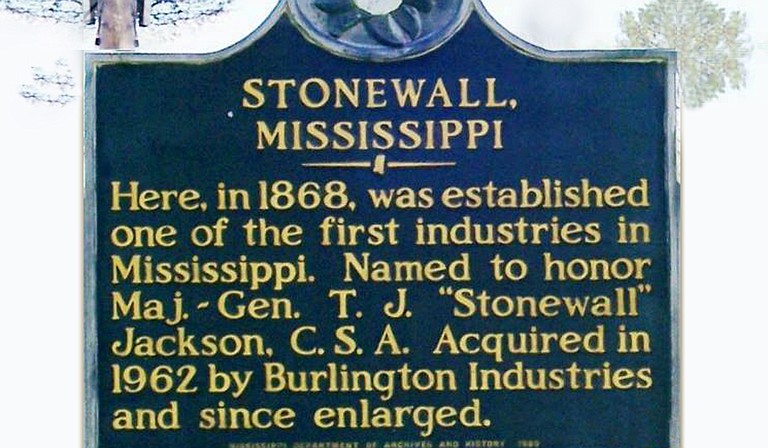

In Stonewall, named for Confederate General Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, the racial demographic breakdown—75 percent white and 24 percent black—doesn't quite mirror the state's overall population, which is 37 percent black. Photo courtesy Facebook

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

One week after the death of Jonathan Sanders, a black man killed after a white police officer stopped him in the east Mississippi town of Stonewall, a clearer picture of tensions between local law enforcement agencies and the African American community is starting to emerge.

In Stonewall, named for Confederate General Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, the racial demographic breakdown—75 percent white and 24 percent black—doesn't quite mirror the state's overall population, which is 37 percent black.

Racially speaking, Clarke County, where Stonewall is located, looks more like the rest of the state, but African Americans don't have the numbers that exist in other areas of the state to have a significant presence in elected offices.

"Race relations in Clarke County are just like any other place. There are people who get along, but you still have your segregation," said Lawrence Kirksey, the president of the Clarke County chapter of the NAACP.

Kirksey pointed out that police roadblocks are more likely to be found near black neighborhoods than white parts of the county.

Blacks are also more likely to be harassed, but few records exist because most African Americans don't bother to make formal complaints against police agencies in Clarke County, Kirksey said.

"A lot of times, when you complain about a white officer, nothing gets done," he said.

'You Can't Speed on a Horse'

Sanders himself seemed to be experiencing antagonism with the police before he encountered Officer Kevin Herrington on the night of July 8. Attorneys for Sanders' family say that before his death Sanders complained of police harassment.

J. Stewart Parrish confirmed to the Jackson Free Press this week that he was representing Sanders in a forfeiture case, which he explained this way: "A forfeiture action is when the government comes in and says they want to take your stuff because they believe you are selling dope."

Parrish declined to discuss the case in detail and referred other questions to attorneys with Lumumba & Associates, the Jackson firm representing Sanders' family.

In 2003, Sanders was convicted of selling cocaine and had several other arrests over the years. Public records show that he was discharged from probation for the cocaine conviction in May 2007.

At the time of his death, he had no active warrants, however, his lawyers told the Jackson Free Press.

Other black citizens in Stonewall have similar complaints about harassment by white police officers. One woman, who asked that we not print her name, told the Jackson Free Press in a message that once, while driving in a car with her fiance, a Stonewall police officer pulled them over. The officer declined to issue a ticket, but did follow the couple for about a mile to their home, she said.

Stonewall Police Chief Michael Street said receiving a call from the Jackson Free Press was the first time he'd heard that some people in the community are afraid to file complaints against officers, but that his department has an open-door policy.

Still, the Sanders family's attorneys, Chokwe A. Lumumba and C.J. Lawrence, recently described to the Jackson Free Press a series of events that started with what they believe was Herrington unnecessarily following Sanders.

"You can't speed on a horse," Lawrence said. "What crime could you have committed that would require a violent takedown?"

A Mystery Companion

The attorneys told the JFP that around 10 p.m. on July 8, Sanders, who was sitting in a buggy being pulled by a horse, observed Herrington speaking with a man Sanders knew at the Cefco gas station in Stonewall.

The attorneys say when Sanders rode by, he told Herrington to leave the man alone. The lawyers declined to identify the man at the gas station, except to say that he is white.

Based on the testimony of other witnesses who live near where the scene played out, Herrington caught up with Sanders down the road and flashed the blue lights of his squad car. Sanders' horse reared up, presumably frightened by the lights, knocking Sanders from the buggy and causing the headlamp he was wearing around his head to fall around his neck. The horse started to run off, and Sanders ran after him.

According to the lawyers, witnesses say Herrington chased after Sanders, grabbing at the headlamp around his neck and pulled him to the ground, which the attorneys believe could be where early false reports came from about Herrington using a flashlight to subdue Sanders. From there, Herrington spun Sanders around and applied a headlock, they said.

Witnesses told the lawyers that Sanders was face down with his hands underneath him; Herrington was on his knees in front of Sanders, they said. By then, several neighbors had gone outside, including a witness who told Herrington that Sanders would not be able to breathe with his face buried in the tall grass.

The attorneys say that Herrington had a female companion with him in the police car, who was not an officer. As Herrington applied a chokehold, attorneys say, the officer instructed the female companion to remove his gun from its holster so that Sanders could not reach it; however, the woman could not unholster the weapon, but one of the witnesses was able to tell her how to remove it.

Witnesses told the attorneys that Sanders said at least twice that he could not breathe, attorneys say. Another witness went home and got a mask that would enable them to perform CPR just in case it was needed.

Attorneys say Sanders never fought the officer and did not move throughout the incident. Herrington did not let the witness perform CPR and maintained the headlock until backup and emergency-medical technicians arrived as much as 30 minutes later, the attorneys for the Sanders family say.

The attorneys, Lumumba and Lawrence, said Sanders had no active warrants and cannot understand why Herrington would follow Sanders.

It Was Shocking'

Eventually, EMTs placed Sanders in an ambulance, but the lawyers are unclear on the time of death. They have yet to see the autopsy report, which was not released by press time. Sanders' body was returned to Clarke County for his funeral services this weekend, July 18 and July 19. Lawrence, one of the attorneys, said the autopsy information is necessary in order to put Sanders, the father of two children, to rest.

"His mom is obviously hurt. She's a strong woman," Lawrence said. "She's trying to manage."

The Mississippi Bureau of Investigation is handling the case. Warren Strain, an MBI spokesman, said the same team that investigated the shooting deaths of Hattiesburg police officers Benjamin Deen and Liquori Tate is handling the Sanders death probe.

A community meeting took place Tuesday night in Stonewall. Speaking to the Jackson Free Press before the meeting, Kirksey, the NAACP leader, said he would attend but that the meeting was unlikely to ease tensions.

Asked if he was surprised by the incident, Kirksey said: "I think the surprise was that it had never happened before. It was shocking that it happened in that way."

Read more of JFP's coverage of Jonathan Sanders' case here.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID