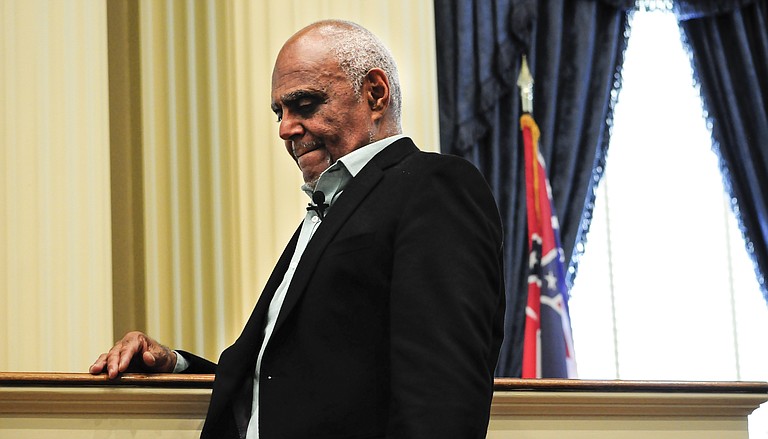

Bob Moses helped end Jim Crow in Mississippi 50 years ago. He still wants equality in education. Photo by Trip Burns.

Wednesday, June 4, 2014

Dr. Robert Moses Jr., an architect of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project in 1964, connected the Jim Crow policies of the past with the underfunded education of today during his talk Monday at the Old Capitol Museum in downtown Jackson. The first in the new Medgar Wiley Evers Lecture Series coincided with the opening of "Stand Up!: Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964," which will be housed in the William F. Winter Archives and History Building. Moses spoke in the old House of Representatives Chamber of the Old Capitol—where Mississippi voted to secede from the union in support of slavery on Jan. 9, 1861.

During the lecture, Moses, 79, led the diverse audience through a short history of black disenfranchisement in the United States and what he called a partial evolution of just who qualified in the U.S. as a "constitutional citizen." His timeline began with the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and ended with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Along the way, Moses compared the "guerilla struggle" he and other civil-rights leaders shared from gaining rights for black voters in the 1960s to the mission of The Algebra Project, a nonprofit group he founded to help students of color use math to transcend what he calls the "sharecropper education" too many of them receive.

"(We've) gotten Jim Crow out of public accommodations, the right to vote, and the national Democratic Party," Moses said. "... we didn't get it out of education."

Moses spoke of white Democrats fighting to keep slavery and then Jim Crow in place, especially in the South, and when Republicans, then black, were "annihilated" when they tried to serve public office and bring equality to non-whites after the Civil War. Their efforts ended in Reconstruction and a compromise that allowed white Dems to force segregation until the 1960s—when Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party pressured Democrats at their national convention to reject Dixiecrat ways and embrace federal civil-rights and voting-rights legislation. (That political shift also resulted in a Republican shift into a mostly white party that opposes equality legislation such as the Voting Rights Act.)

Hamer, he said, was "incapable of being inauthentic ... she spoke from the whole history, not just of herself but the state she loved so much."

Moses also pointed out the irony of underfunding and restricting access of African Americans to a quality education for years—and then trying to use illiteracy as a way to keep them from voting and participating in the political process.

"When we began, white male property owners were the constitutional people. Do young people deserve constitutional status—for purposes of their education?" he said, adding, "How (do we) get young children to demand their education—that everyone says they don't want?"

"Young people who are 10 to 40 years old now, 30 years from now will be running the country," Moses added, directing his message to a new generation of change makers in America. "You can think that, 'I am a part of this We-the-people; I take personal responsibility for constitutional personhood.'"

Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore, a civil-rights veteran, founding director of the Fannie Lou Hamer National Institute on Citizenship and Democracy and a former Jackson councilman, introduced Moses. "All of these people changed my life," McLemore said, speaking of Moses and other prominent veterans, such as Jackson NAACP leader Medgar Evers and SNCC founder Ella Baker.

Byron de la Beckwith Jr., son of the man eventually convicted of the murder of Medgar Evers at his home in Jackson in 1963, sat on the second row listening to Moses speak. "(I am here) for the knowledge and to learn," Beckwith said after the event. "I got so much information. I am not disputing anything (Moses) said, but I couldn't hear all of it—my hearing is bad." Beckwith was the subject of a recent documentary by Canadian filmmaker Paul Saltzman called "The Last White Knight."

The "Stand Up!: Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964" exhibit is open Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and on Saturday from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. until November. It is free to the public.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID