Photo by Trip Burns.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

In an America where public American narratives of Muslims are limited to images of terrorists and poverty-stricken refugees, our perception of Muslim history may be similarly warped. Especially in a small state such as ours, the scarcity of Muslims to counter the dominant stereotypes about their culture furthers the narrative. That's what makes the work at the International Museum of Muslim Culture so important.

The Jackson museum, the first of its kind in America, provides a valuable resource for both Muslims and African Americans to learn more about their legacy. It's had its ups and downs: After the Sept. 11 attacks, someone threw a brick through one of its windows, which resulted in a massive wave of support from Jackson's government and local colleges and universities.

The museum's exhibition, "The Legacy of Timbuktu: Wonders of the Written Word," highlights how West African Muslims contributed to the world's knowledge and may have even been responsible for your favorite blues song.

IMMC's co-founder and executive director of the exhibition, Okolo Rashid, acknowledges that disrupting false narratives is a central part of her work at the museum. When she gives tours of the exhibition, many visitors are surprised to find out that a huge contingent of black Muslims and that Muslims are responsible for inventions such as the loom.

While the museum is small (it takes up one wing of the Mississippi Arts Center, where it moved in 2006) and lacks the deep pockets of big museums such as the Smithsonian, word of mouth and public support has ensured the museum's residency in the Jackson area since 2001.

"It's because the significance of the story (of African Muslims) and the lack of knowledge behind it," Rashid says.

"The Legacy of Timbuktu" exhibition tells the story of Timbuktu and the surrounding region's economic and educational prosperity. The exhibition opens with a scale-model that University of Mississippi archictectural students constructed of the Great Mosque of Djenne, the first university in the Timbuktu region. The structure still stands in the city of Djenne today, but only as a mosque "because when the colonizers came in, all the universities were destroyed," Okolo says.

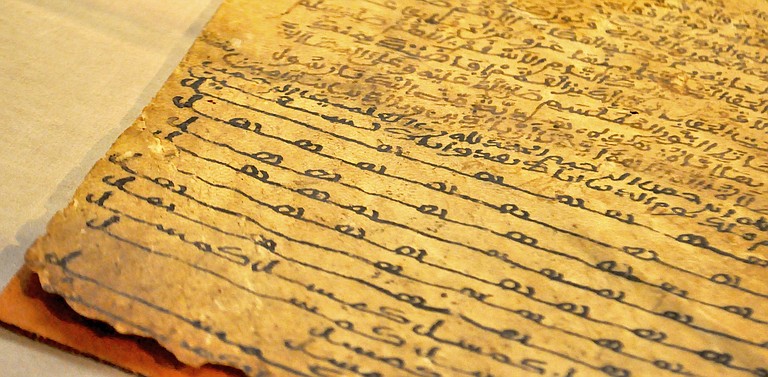

After using an interactive map to track the spread of Islam across Africa, patrons watch a couple of video presentations about the region's contributions and Rashid's trip there to retrieve the artifacts. Museum goers then make their way under a 20-foot by 30-foot camel-skin tent that Rashid and her husband, Sababu, brought back from the region. Blankets, a camel saddle and original manuscripts are under the tent.

Panels on the wall outline the economy of the region during the height of its power. "The most profitable business was book trading," Rashid says. "(Also,) we now know that about two thirds of all the world's gold came from that region."

Manuscripts from world traveler Ibn Battuta said the Timbuktu region was the safest he had traveled, and it also dispelled other Muslim myths. "He also talked about things like women's liberation, and how women were traders and very independent there," Rashid says. "So his story really helps us to shine a light on the region."

The exhibition then moves from the prosperity of the region to the havoc that the colonial slave trade wreaked. "What our studies have shown is that at least one-third of all of the enslaved Africans that were brought to the Americans came from this region," Rashid says.

The exhibition features two stories of enslaved Muslims—Ibrahim Adbar-Rahman, who was a prince in the region prior to his capture and the subject of a recent award-winning PBS documentary, and Umar Ibn Said, who was a schoolmaster and managed to write an autobiography while he was enslaved. "(The autobiography) was the only one of its kind," Rashid says.

The tour ends with an exhibit that draws a direct connection between the Muslim background of the slaves that made up a majority of the American slave population and the Mississippi Blues music that came from those workers. The display prompts the viewer to push a button. A traditional Muslim call to prayer rings out followed by a blues song called "Levee Camp Holler." A plaque next to the button points out the similarity of the vocal tremors and lyrical content. The resemblance is striking.

The International Museum of Muslim Cultures (201 E. Pascagoula St., 601-960-0440) is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday and by appointment only on Saturdays and Sundays. Admission is $13 for adults, $12 for seniors and $7 for students. Visit muslimmuseum.org for more information.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID