Wednesday, November 21, 2012

The rich are getting richer, while the poor are getting poorer. That cliche has never been truer than in Mississippi during the past couple of decades. Nowhere in the U.S. has the inequality gap grown larger than in Mississippi.

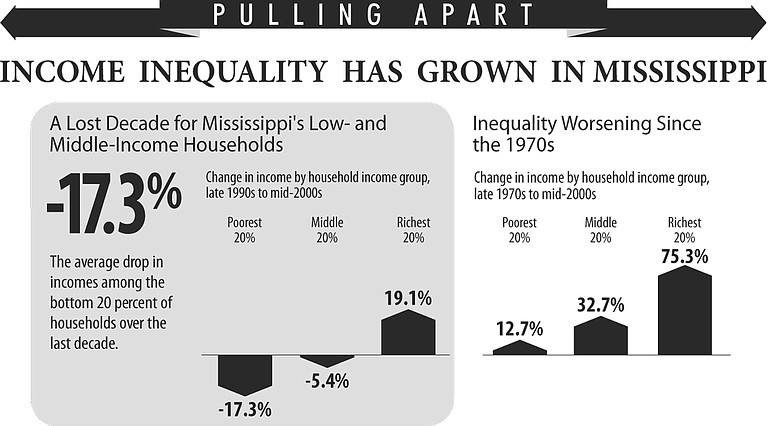

On Thursday, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities released "Pulling Apart: A State-by-State Analysis of Income Trends," a report that focused on the income gaps between each state's poorest families, those in the middle and the richest.

Not a single state in the union saw income inequality decrease by a statistically significant amount. Some saw no changes during the periods examined (1977 to 2010); however, most saw inequality rise.

"It's especially disturbing that the last decade was a 'lost decade' for low and moderate-income households," said Elizabeth McNichol, one of the report's co-authors, during a conference call Nov. 14.

Nationally, between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, income fell 6 percent for poor households and stagnated for middle-income households, growing only 1.2 percent on average, she said. In contrast, high-income households climbed 9 percent, and the richest 5 percent grew by 14 percent.

The national numbers pale in comparison to Mississippi's lost decade. Income for low-income Mississippians plummeted by 17.3 percent during the period, while middle-income households dropped 5.4 percent. The richest 20 percent grew by 19.1 percent. Mississippi's poorest 20 percent of households make an average of $16,100.The top 5 percent? $224,700 a year--14 times that of the poorest 20 percent.

"[S]tates like Mississippi have an opportunity to choose a different course," McNichol said.

CBPP is a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that researches policies affecting low- and moderate-income families. "Pulling Apart" outlined why the gaps exist, what it costs (in terms other than dollars) and provided a number of recommendations for state legislatures.

Income inequality doesn't just hurt the poor. It threatens social cohesion and trust, especially in government and leadership, the report states. It exacerbates crime problems and even undermines efforts to lift families out of poverty, when work doesn't pay enough to live on. "When low-wage jobs do not pay enough to lift a family out of poverty and when the incomes of the poorest families grow only slowly or not at all, policies that encourage work cannot succeed," the report states.

Ed Sivak, director of the Mississippi Economic Policy Center, said one of problems in the state is that the number of jobs hasn't increased since 1996. "Over the last 10 years, we've lost over 88,000 manufacturing jobs," he said. "... These weren't just good- paying jobs; these were good-paying jobs that often offered health insurance."

Mississippi also lost 3,900 public-sector jobs since 2008, and union-membership workers have been cut almost in half since the OK, both of which factor into the loss of good, middle-income jobs.

Today, nearly a quarter of working Mississippians have low-wage jobs, frequently without benefits. With a half-million adults with a only a high-school diploma or less, those workers are "often not going to have the skills to be monetized and move up the economic ladder," Sivak said.

Mississippi's community colleges should provide new job skills to low-income, low-skilled workers, he said, and part of the solution to inequality is ensuring those schools have the resources they need.

The two most important avenues to bring people up from poverty, however, are child care and health care.

"When people have access to good child care, especially if they're working mothers, they're more likely to stay attached to the labor force," Sivak said.

"... Likewise, when someone has health insurance, they are likely to be healthier, more productive; they miss less work."

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act may be the greatest opportunity to shrink the inequality gap.

"First, it would create jobs," he said-- about 9,000 a year by the MEPC's estimation. It would also provide health insurance to more than 300,000 people.

"If Mississippi doesn't more forward with Medicaid expansion, not only do we miss out on that opportunity to create jobs, but our workforce will be less healthy, our private insurance premiums will increase, and that's going to make us, overall, less competitive when trying to attract industry to the region. ... It's an immediate way for us to address income inequality in the state."

Sivak added that the state's tax system is highly regressive. "A family earning $35,000 a year is in the same tax bracket as a family making a $1 million a year," he said.

In addition, Mississippi's sales taxes on necessary items--food, for example--is much more of a hardship on the poor than on the wealthy. "We need to have a revenue system that is balanced," he said, which would include adding at least one additional tax bracket on the high end of the income scale and closing corporate loopholes."

"Another thing you could do is broaden the sales tax base," Sivak added. Mississippians don't pay sales tax on most services--dog grooming, for example. Adjusting the base could generate more revenue and make the system fairer. "When you tax things that people can't avoid purchasing, that makes the system, overall, more regressive," he said.

Mississippi also had the fastest-growing gap between the rich and those bringing home middle-income wages, around $46,000 a year.

"What you will see is increased segregation by income," he said. With that comes an erosion of support for the fundamentals of our educational system--public schools and affordable college tuition.

"As support for those things erodes, then we all lose out," Sivak said. "... It puts us in a place where we limit our potential."

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID