Wednesday, October 26, 2011

A decade ago, Johnny DuPree, while running for re-election to the Forrest County Board of Supervisors, answered a phone call from then-Lt. Gov. Ronnie Musgrove asking for help with his campaign for governor.

DuPree, cruising toward re-election in south Mississippi, helped shepherd Musgrove to area high-school football games and African American churches.

By this time, DuPree had lost his first bid for mayor of Hattiesburg and hadn't decided whether to try again. The University of Southern Mississippi graduate helped many Democratic candidates connect with voters in the area and contributed his connections to Musgrove's successful 1999 campaign seemed like second nature.

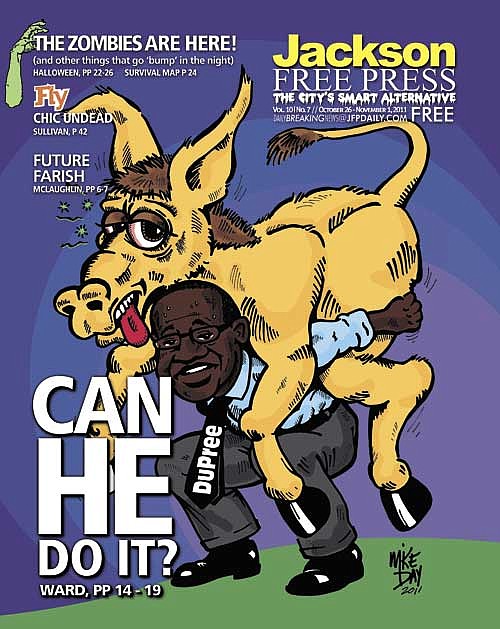

The county supervisor couldn't have imagined the foreshadowing happening at the time. For a year and a half now, DuPree, 57, has made those same requests, asking for help from people throughout the state, looking to be elected governor of Mississippi this Nov. 8.

"It was a unique coincidence," DuPree said recently of helping Musgrove reach out to voters. He was traveling from a Jackson campaign fundraiser back home to Hattiesburg. "Now, we're doing the same thing."

Times have changed for DuPree, the state Democratic Party and the overall political landscape compared to a decade ago. One of the more obvious changes: The nation elected its first black president. For DuPree, he's now finishing his third term as mayor of Hattiesburg.

However, a key question remains unanswered: At a time when convincing white voters to support even white Democrats is difficult, does the Mississippi Democratic Party have the organization in place to help a black man become governor?

Dem Dysfunction?

The quip by the late American cowboy and humorist Will Rogers about his politics never goes stale. "I'm not a member of an organized political party," he said.

"I'm a Democrat."

To the chagrin of Mississippi's Yellow and Blue Dogs—Yellow Dogs are Democrats who would vote for a yellow dog over a Republican, and Blue Dogs are more conservative Democrats who sometimes vote with Republicans—in most of the Magnolia State's 82 counties, Rogers' humor still reflects a grim reality.

It's easy to spot the dysfunction in today's state Democratic Party.

For starters, look at the top leadership post of party Chairman Jamie Franks, a failed lieutenant governor candidate and former state representative from Mooreville in northeast Mississippi.

While Franks should have been out finding potential candidates to run for statewide office over the last couple years, he spent time embroiled in a scandal involving his now-former wife Alisa's extramarital affair with another public official.

Earlier this year, news accounts quoted Franks as saying he felt "vindicated" after a judge dismissed a lawsuit against him filed on behalf of Lee County School District Superintendent Mike Scott, who claimed Franks committed extortion by pressuring him to resign for having an affair with Franks' wife. Jamie and Alisa Franks divorced in June 2010.

Also distracting for Franks' leadership role with the state party, he decided to run this year for his former seat in the state House of Representatives. He lost in the primary election after trashing a fellow Democrat, Mark DuVall, accusing him of not being Mississippi—or pro-life—enough to represent his former district.

Franks sounded like a Republican as he slammed his opponent for supporting legislation limiting the use of unmarked cars in drug raids, saying DuVall had "stood up for drug dealers."

"Over the past four years, we have had somebody that has not stood up for Mississippi values, but somebody who has stood up for the values of some other state like California," Franks said in a radio interview during the primary.

Franks isn't expected to seek another term as Democratic Party chairman when his term expires this year—probably to the dismay of Mississippi Republicans.

To help clean up some of the mess within the state party, Franks called on produce farmer and former state Democratic Party Chairman Rickey Cole to serve as executive director of the state party. Cole began in the position Aug. 29.

Cole's time in his previous party position coincided with Musgrove's term in office, 2000 to 2004, the last time Democrats had a strong grip on statewide offices.

A Long Slog

A self-described Yellow Dog Democrat, Cole is traveling the state again trying to rebuild his party's organization and credibility. Since he began his position about two months ago, Cole has logged 10,000 miles in his 2005 Crown Victoria, a retired highway patrol vehicle he bought at an auction two years ago.

In 1999, Democrats held all non-federal, statewide offices except for auditor, held then by Phil Bryant, first appointed to the position by former Gov. Kirk Fordice, the state's first Republican to hold the state's top government job since Reconstruction when the GOP was a very different party.

Now, Democrats find themselves on the losing end of this role reversal, holding only the statewide office of attorney general, held by Jim Hood, who supports the death penalty, the personhood anti-abortion initiative and other conservative social positions.

Compared to 2007 statewide primaries, about 400,000 voters voted in this year's Democratic Primary, nearly a 12 percent decrease. For Republicans, about 282,000 votes tallied in their primary, showing a nearly 43 percent increase. The trend looks even starker when compared to just 24 years ago. In 1987, 18,853 people voted in the Republican primary, while more than 800,000 voted in the Democratic gubernatorial primary.

Cole's streaks of gray hair, along with his conservative suit and yellow tie, may fool many people into thinking the Ovett native with a deep southern drawl has been around longer than his 45 years.

Before sitting down in a booth at Harvey's restaurant in Starkville, Cole handed me a news release from the Mississippi Democratic Party questioning the homestead exemption filings of Republican Deborah Tierce of Fulton.

"I like to go on offense when we can," he said with a half grin.

A Democratic Party activist since 1982, Cole enjoys the horse race of politics. He likes finding mistakes the opposition makes and isn't afraid to exploit them, such as in a press release he sent out this week stating that Republican candidate Steve Simpson "should withdraw." In it, Cole accused Simpson of falsifying state documents to pay for a $400 steak dinner. (An hour and two minutes later, an email from Simpson accused his opponent of "negative, personal attacks"—and asked for donations.

"I tend to think nice guys finish last," Cole said. "The two party-system is important to keeping the other side on its toes."

Cole spoke candidly about the current state of the Mississippi Democratic Party. He didn't hide his shame in the party failing to field candidates for three statewide offices and high-quality, viable candidates for each of the eight statewide offices on the ballot in November.

Along with Attorney General Hood and DuPree, other Democratic candidates for statewide elections appearing on the ballot include Ocean Springs Mayor Connie Moran for state treasurer, Pickens Mayor Joel Gill for commissioner of agriculture and commerce, and former Moss Point Mayor Louis Fondren for commissioner of insurance.

"It's embarrassing to not field a candidate for the open seat of lieutenant governor," Cole said. "It's equally as embarrassing to field a candidate who doesn't have a chance."

While some candidates like Gill have developed an air of unelectability, candidates like Moran appears to be a solid choice with an impressive record—but with little party support.

A decline in Democratic candidates, voters and organization says a lot, but that doesn't cover all the state party's pains these days. The "race issue" and lagging fundraising also continue to worry party insiders.

Few people dispute that voting patterns in the South follow racial patterns, especially in Mississippi where 2008 exit polls showed that 88 percent of whites voted for John McCain of Arizona in the presidential election, while 98 percent of blacks supported Barack Obama of Illinois. African Americans comprise 37 percent of the state's population, the highest proportion of blacks in any state. But compared with the white population of more than 59 percent, which is overwhelmingly Republican these days, voting along strictly racial lines makes Democrats a long-term minority party, literally and figuratively.

Democrats in the state don't seem have a confident response when asked if whites will vote for a black Democratic gubernatorial candidate. "We'll find out on Election Day," Cole said simply.

Southern Strategy

Don't forget that the party of civil-rights activists Aaron Henry and Fannie Lou Hamer also shares roots with segregationists Jim Eastland and Ross Barnett. However, most of the political grandchildren of Eastland and Barnett have migrated to the state GOP, part of Richard Nixon's southern strategy to appeal to white racists in the Democratic Party.

By the time Ronald Reagan—with young Republican strategist Haley Barbour cheering him on—borrowed the approach for drawing white southerners to the so-called "Party of Lincoln," language had become less racially overt, with phrases like "states' rights" replacing the overt bigotry of Barnett and friends. "State's rights" became code for a position by many segregationists and those who opposed civil-rights legislation, claiming that each state should have the right to decide for itself whether to integrate public schools and other laws that benefited African Americans.

Jackson State University professor and head of its Department of Political Science D'Andra Orey said the late political scientist V.O. Key's racial-threat theory explains why Mississippi politics has become more racially polarized. "In high concentration areas of blacks, whites felt threatened that they would lose their power in the Democratic Party. Many of those conservative, white Democrats have realigned with the Republican Party," he said.

Differences remain between blacks and many white Mississippians still in the Democratic Party. Marty Wiseman, director of Mississippi State University's Stennis Institute of Government, said one key difference between many black and white Democratic candidates seeking office involves a willingness to associate with the national Democratic Party. Most white Democrats keep their distance from Washington and the national party, even as Republicans try to connect them at every turn, especially on signs at the Neshoba County Fair drawing parallels between white candidates and black Democrats such as Obama and U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson.

Wiseman said hot-button, national issues like abortion and gun control have most white Democrats holding national party leaders at more than an arm's length.

Black Democrats in the state, however, remain comfortable associating with national Democrats, particularly Obama, who turned a record number of them out to vote for him. As for shared political values, blacks and whites in the Democratic Party today have more in common than ever before, including conservative views on issues like abortion and gay marriage. "Black Democrats are fairly indistinguishable from Southern whites with religion, church affiliation and so on," Wiseman said. "Liberals in Mississippi are few and far between regardless of color."

"Many of the conservative Democrats left over from the segregationist era have crossed over to the Republican Party," Wiseman said. "So not nearly the split remains in the Democratic Party that did exist."

Defending the Social Contract

Cole said segregationists migrating to the GOP helped the Democratic Party focus on "Democratic values" that make sense for Mississippi voters, although the party executive director refuses to give examples of those values. Instead, he says Democrats generally value people in communities working together for common goals while Republicans tend to be more individualistic.

"We're the defenders of the social contract," Cole said of Democrats. "You won't hear me give a laundry list of what it means."

As for long-term plans, Cole sees the Mississippi Democratic Party's role as the appropriate structure to expand the Democratic base in the state as close to 50 percent as possible. To recruit more Democratic activists, he believes it's vital to not pay attention to labels or identification like conservative or liberal, rich or poor, black or white. He said they should come from all walks of life, incomes levels, shapes and colors.

"One thing about Mississippi Democrats," Cole said, "they certainly defy all stereotypes," describing a "potbelly farmer" like himself as an example.

The state party under Cole's leadership will further develop databases of voter information to help candidates and party leaders identify Democratic voters and those who could be swayed to vote for Democratic candidates, he promised. Using social media and new technology to target people to support Democratic candidates also will play a role in expanding the party in the state, while Cole still places heavy emphasis on having the party's presence seen and felt at functions and events all over the state.

"We have to do a better job of marketing," Cole said. "I think we have a competitive brand, but we have to do better."

The Elusive 'Middle'

"The gold right now is in the middle," Cole says of independents in the state.

Political scientist Wiseman said while surveys show 50 to 60 percent of the state's voters identify as Republican, that number can mislead. "Regardless of what they say, Mississippi is at least half or better independent in reality, although it leans Republican," he said. "Basically, the bulk of Mississippians prove to vote independently."

So which issues resonate with independents? Is it social issues like abortion and opposition to gay marriage as so many Republicans and Democrats seem to believe? Not according to this state Democratic Party veteran. "Everybody I talk to is concerned with the economy," Cole said. "Mississippi's unemployment went up again last month. We're seeing some pretty desperate times all over the country."

State Democratic Party leaders see economic issues as key to regaining some of the political ground lost in recent years. They see job creation and getting the unemployed working again as key issues—issues that don't seem to be resonating on Democrats' behalf in today's Mississippi. When asked how state Democrats have communicated these ideas and positions, Cole resisted, saying he had only in his position for a few months.

Legacy of 'Tort Reform'

The question on many minds today is: Can Mississippi Democrats find the right formula to win more than a single statewide election, if that, in November?

At least one answer is: They may not be able to afford it—especially against Republican opponents who are well funded by business interests backed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Political parties and individual candidates need resources to help get the public's attention and reach independent voters—and Mississippi Democrats' main source of cash dried up, starting on a Democratic watch earlier this decade.

Ronnie Musgrove's term as the last Democratic governor isn't a coincidence to many political observers. He seemed to commit Democratic Party treason by promoting "tort reform"—the phrase most commonly applied to limiting the financial compensation juries can award to plaintiffs in excess of actual damages.

To many Mississippi plaintiff attorneys, often called trial lawyers, Musgrove—a lawyer—bit the hand that fed him and other Democrats. He led the effort that resulted in slashing incomes of the most generous donors to the Democratic Party—a result astute political watchers know is one of the major goals of tort reform.

Recounting the Aug. 23, 2002, breakfast between Musgrove and trial lawyers who had supported him, the book "Mississippi Politics: The Struggle for Power, 1976-2006" described the governor explaining to his key financial contributors that political pressure had become too much to ignore.

"Now a Democratic governor would begin the process by which the single largest source of funding for Democratic candidates would be permanently undermined," Jackson-based Democratic consultant and co-author Jere Nash wrote.

Nash, citing connections to candidates in the Nov. 8 election, declined to comment for this story.

Wiseman elaborated, however, saying that Musgrove thought the media spotlight on a number of multi-million-dollar jury awards in places like Jefferson County caused massive pressure to pass tort reform. Phrases like "jackpot justice," repeated often in state media such as The Clarion-Ledger, created public sentiment for limits on punitive jury awards.

(The media fixation on "runaway juries" ignored evidence, published by the Government Accounting Office of Congress and other researchers, that "lawsuit abuse" was overblown by business interests and the GOP in states including Mississippi.)

Musgrove responded to the hype by getting behind tort reform. "They were flabbergasted that one of their own would open legislation like this," Wiseman said of trial attorneys.

After Musgrove lost the governor's mansion to longtime GOP strategist and lobbyist Haley Barbour, the state's second Republican governor intensified tort reform that the Democrat started, further decreasing income for trial lawyers—and contributions to state Democratic candidates.

"He's a master of unleveling the playing field in a legal way," Wiseman said of Haley Barbour. "He knew signing tort reform would end up cutting down the money available to the trial lawyers, who were 90 percent Democrat."

Cole, taking a circumspect approach to Mississippi Democrats' fundraising problems, said the state Democratic Party made a giant mistake years before Musgrove's special session by largely counting on a single source of donations.

"No political party should depend largely on one business sector, one interest group for its revenue," he said. "It didn't serve the party well or the trial lawyers, either."

For Democrats depending so much on trial lawyers, the party gambled by not diversifying and reaching out to more types of potential donors. "If all of the doctors in Mississippi had their income cut by two-thirds, the Mississippi Republican Party would still be funded," he said.

For Democrats to gain enough resources to help candidates stay competitive, they will need to broaden fundraising nets to include smaller donors. Cole said the state party's biggest revenue stream will soon be repeat donors, many giving $10 to $25 month. He has a goal of having 1,000 donors contribute $10 a month by 2012. Now, 140 contributors give that much each month.

Cole believes more small donations will come as the public sees a more organized, aggressive Mississippi Democratic Party. "People don't want a political party that rolls over and plays dead," he said. "We're not going to do that anymore."

And as if anyone could forget, the state economy continues to sag, making fundraising even more difficult and $200 or less donations even more critical. "The way you do it is to ask, ask, ask," Cole said.

Wiseman says the Democratic Party must rebuild almost from the ground up. He points out how few young people seem attracted to the Mississippi Democratic Party now. "As support is galvanized by the Democratic Party, that will begin happening with young people," Wiseman said.

"I'm saying this in the context of 'when' it happens, but there's probably a question of 'if' it happens, too."

Hell Freezing Over?

While hell didn't freeze over when the nation's electorate chose an African American for president, it's hard not to wonder what will happen if Mississippi—the most Dixie of southern states—elects a black man to the state's highest office.

Will the sky open up and lightning strike everyone who made it happen? Will property values plummet from Southaven to Madison to Bay St. Louis? Will all businesses leave the state in search of a place with elected officials with less melanin?

After all, that's what happens when cities elect African Americans as mayors, right?

Just look at Hattiesburg—a city of 45,989 residents and home to the University of Southern Mississippi and William Carey University—since DuPree began leading the city in 2001.

When the father of two daughters decided to run for mayor of the Hub City, a number of whites throughout the city whispered that crime would run rampant and property values would drop.

Twenty-five-year Hattiesburg resident Paul Laughlin, a trust officer at a local bank, recalls hearing whites in the city voice concerns about a black man elected to run the city, including fears that a black mayor would be soft on crime.

Not true, said Laughlin, who is white. "They seem as zealous in curbing crime as much as their predecessors did," he said of the DuPree administration. Laughlin hasn't made up his mind on who will get his vote for governor in just under three weeks, but he has appreciated seeing growth and progress in the Hub City during DuPree's time in office. He especially appreciates the community's focus on renovating properties around the downtown train depot, a place in disrepair for decades.

"There was a reputation that downtown was a high-crime area," Laughlin said. "People have realized that's not the case."

When Allan McBride—chairman of the University of Southern Mississippi's Department of Political Science, International Development and International Affairs—moved to Hattiesburg in 1996, he and his wife, a public school teacher, found the community's support for public schools a big draw. He stills sees a group of committed parents, teachers and an engaged community supporting public schools. McBride also appreciates downtown revitalization efforts and business growth in the city.

"If DuPree hasn't been specifically responsible for this, he certainly hasn't blocked it," McBride said.

"That's also a sign of leadership."

In his third term, DuPree enjoys sharing Hattiesburg's story. Addressing groups, festivals and other gatherings throughout the state, he talks about jobs that have come to his city even as the nation struggles economically.

"Healthier, more educated, wealthier—that's for formula for getting rid of poverty," he said at a banquet in Booneville for the Eliza Pillars organization, a black nursing association.

"All of us want the same things," he said at the nurses' banquet. "We all want a better community." The audience responded to his message, applauding.

Contrary to skeptics' warnings, DuPree's record in Hattiesburg shows an African American can lead a prosperous city, even help grow it stronger. DuPree brags on his city—pointing out that the Blue Cross & Blue Shield Foundation of Mississippi named Hattiesburg the largest, healthiest city in the state this year, how the city has prioritized healthy infrastructure like bike paths and sidewalks, how the citywide smoking ban has helped freshen up everybody's air.

"Just this month, a Hattiesburg neighborhood made history as the first in the state highlighted in the American Planning Association's annual list of 10 great neighborhoods," DuPree told the Booneville nursing banquet.

He kept gushing about his city and the partnerships that made progress possible. "It took us three years, and we brought everybody to the table," DuPree said. "But now, we have a smoke-free city. We have some of the best neighborhoods in the state. We have more jobs, and we didn't raise taxes."

Rock Star Candidate

As DuPree campaigns throughout the state with his wife, daughters and grandson joining whenever they can, crowds of African Americans greet him with a rock star's welcome. At JSU's homecoming football game weeks ago, large pockets of supporters in the crowd cheered for him almost as loudly as when the Tigers scored a touchdown. Fans in the crowd stopped him to have their photos taken with him. Others shouted "DuPree" and "Governor" as he passed.

Many in the black community say DuPree represents much more than a long-shot politician facing a mighty challenge against the GOP's juggernaut (and Tea Party-courting) nominee, Phil Bryant, the current lieutenant governor.

Older African Americans and their children in the state say DuPree brings something to Mississippi they never thought they would live to see—a man with their skin color running for the state's highest office, who decades ago would get the hell beat out of him, even murdered, just for trying to vote.

Sheaneter Johnson, 53, a Nettleton native who attended DuPree's speech in Booneville, sees this election as important as ever for the African American community to elect one of their own as governor.

"Because of people who died before us to make this happen, we have to keep carrying on their voices," Johnson said. "We have to make this happen."

From black nursing organizations to churches to fraternities, African Americans in Mississippi seem focused and ready to help elect Mississippi's first governor of color. DuPree's deputy campaign manager, Tyrone Hendrix, spoke like a man on a mission. His background as the Mississippi director of Organizing for America—President Obama's political organizing group, now a part of the Democratic National Committee—has prepared Hendrix for finding as many people in the state who may consider voting for Mayor DuPree.

But will a hyper-focused campaign of organizing be good enough to win? When asked if enough whites will vote for him, DuPree pointed to his time in Hattiesburg. "All I can do is what I'm doing," he said. "I have a history of working with people from all walks of life and was elected by votes from people of many different groups."

Hendrix sounded confident when asked about whites in the state being willing to choose the Hattiesburg mayor over GOP nominee Bryant.

"If anything we've seen in the last few weeks is an indicator, we'll have significant white vote—not just white Democrats, but independents and Republicans," he said. "People look at Mayor DuPree's record and see he's the best candidate."

Driving a Wedge?

Voters will decide Nov. 8 more than just which candidate they want in office. They will also decide on three separate initiatives related to eminent domain, voter identification and a legal definition of "personhood."

All political observers contacted for this story expect each initiative to pass. However, which candidates and party will benefit the most from them on the ballot remains unclear.

While DuPree and Bryant both endorsed the personhood amendment to the state constitution, religious fundamentalists have strong support for it, while many moderates, liberals, medical professionals and even clergy oppose it. Some concerns include unintended consequences related to how the legal definition of personhood can affect procedures such as in vitro fertilization and block common forms of birth control.

Bryant supports voter ID, and DuPree is against it. During the most recent legislative session, the House and the Senate passed a bill requiring identification before voting, but Gov. Barbour vetoed it because of his opposition to a provision that would also allow early voting.

Voter ID has become a political hot button for Republicans who say it will help curb voter fraud (although voter fraud tends to be with absentee ballots, which wouldn't be affected), and for older African Americans—a staple in the Democratic Party base—who still have sharp memories of poll taxes and other trickery used to disqualify them from voting many decades ago.

As for the eminent-domain initiative, it seems to be the least partisan of all on the ballot, Wiseman said. This populist referendum first received support from the farming community, specifically Mississippi Farm Bureau. If passed, it will limit government's authority to take individuals' property for the purpose of private, commercial projects. Bryant and DuPree have both endorsed this initiative, while Gov. Barbour opposes it, saying the change would hurt economic development of future large projects such as automotive plants.

Beyond Election Day

Before state Democratic Party Executive Director Rickey Cole left that Starkville restaurant for Jackson, he seemed defiant in a state whose political landscape has changed so much in recent years.

"Republicans have succeeded too often because we've conceded the field," he said. "As we make changes, it's going to be less easy for them to win by default."

The Mississippi Democratic Party has found a fighter in Johnny DuPree. Weeks from the general election, he and his wife, Johniece, continue to visit as many festivals, football games, coffee shops and all other sorts of events dotted all over the state.

Having the same position as Republican Bryant on the personhood initiative, DuPree has positioned himself as fairly conservative on social issues; however, he stands traditionally Democratic on the issue of education. These stands can't hurt DuPree in the eyes of some whites who would consider voting for a Democrat.

Wiseman said one of DuPree's possible strategies to winning could involve staunch support for public education and support for the state employee retirement system (PERS), whose future remains uncertain after Gov. Barbour created a group to study changing it.

Even with aches and pains from the campaign trail, DuPree said no one should expect him to slow down before Election Day. He mentioned his days of running track in high school. He didn't run to the finish line; he ran "through" it.

"That's been my attitude about this campaign from day one," he said.

As the DuPree campaign gathers at the Lake Terrace Convention Center in Hattiesburg the night of Nov. 8, they and the rest of the state will find out if organizing efforts accomplished enough support to win the governor's mansion.

For the Mississippi Democratic Party, this election's results will give party leaders an idea of how much rebuilding they have to do—and perhaps how. Rickey Cole has an idea of what needs to happen to win elections, but he knows it will take resources, racial unity and optimism. For now, he counts just showing up as a small victory.

"I don't have to be a magician," he said. "This isn't rocket science, but we're all looking for the winning formula."

Read more campaign coverage and candidate interviews at http://www.jfppolitics.com.

Disclosure: While a student at USM, freelance journalist Robbie Ward campaigned for DuPree's second mayoral campaign. Later, he became an editor of USM's school paper and started covering DuPree as a journalist.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID