Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Normally when I go to art exhibits, I don't think about who donated or sold the work to the gallery, much less consider their personalities or who they are as people. But in "Herb and Dorothy: A Glimpse into their Extraordinary Collection," the donors are just as much a part of the exhibit as the artwork. The exhibit, currently at the Mississippi Museum of Art and part of the "50 Works for 50 States" project, intertwines the lives of Herb and Dorothy Vogel with their art collection, and it is more satisfying to view the works knowing about them, than to not think about them at all.

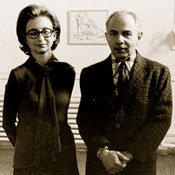

Though by no means rich (Herb was a postal worker; Dorothy, a librarian), the Vogels collected more than 4,000 works of art throughout their marriage. The couple started collecting art in the 1960s, devoting Herb's salary to art purchases. After stuffing more than 2,000 works into their tiny Brooklyn, N.Y., apartment, they started donating pieces to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1992.

Both slight of build with heavy New York accents, Herb and Dorothy, whom you meet throughout the exhibit, seem lovable and down to Earth. Neither is an artist, except for a short stint early in their marriage when they rented a studio and tried to paint. They soon realized they enjoyed viewing others' works more than creating their own and, thus, began a life of collecting. They became good friends with many artists. And knowing the artist, the art had more meaning.

Many pieces directly address Herb or Dorothy. Will Barnett's "The Cardplayers" (graphite on parchment paper) is inscribed, "Happy Birthday Herb from Will and Elana."

The National Gallery of Art granted the 50 works to the Mississippi Museum of Art through the "50 Works for 50 States" program. The art is diverse in range, falling within the conceptual, abstract expressionist, minimalist and post-minimalist categories. Many of the works date to the 1960s conceptual movement, when the idea behind the art was just as important (or more important) than the finished product.

Cindy Sherman's untitled gelatin silver print is a perfect example of a conceptual piece. The photo shows a woman wearing what looks like a nun's habit, a face full of make-up, her head thrown back and eyes diverted away from the camera's lens as if to say, "Look at me; look right at me, though I cannot look at you." One feels almost voyeuristic looking at it. Sherman posed in and photographed all her own work, commenting on society by transforming herself. This photo, in particular, comments on the dual role women often play: chaste and sexy, virgin and whore.

Because many of the works in this exhibit are minimalist drawings, the mediums are significant. For example, the paper and graphite used in many of the drawings become part of the visual image. This is most evident in pieces like the untitled 1976 Michael Goldberg ink on paper, with the paper torn and molded to become part of the image.

Two standout pieces are Charles Clough's "Con-Flagrant" and "Retiarius." The artist put layer upon layer of enamel on canvas in the former and masonite on the latter to create seemingly never-ending pieces that mimic the themes of the "Herb and Dorothy" exhibit itself: What is behind the art? And then, what is behind that? And then, what is behind that?

A particularly intriguing piece—and arguably one of the strangest—is Takashi Murakami's sculpture "Oval." A cartoon character sits atop a ball covered in plastic flowers, anime-like with a big head and huge rounded eyeballs. Murakami had formal training in the Nihon-ga style of traditional Japanese art, but he uses contemporary figures in his work, often expounding on opposites: What is considered high and low art, past and future, eastern and western? It may be why Herb and Dorothy chose to purchase this piece. It encompasses everything they stand for: They live on meager salaries in a tiny Brooklyn apartment but are avid art collectors, a practice usually reserved for those among the upper echelons of society. They defy most collectors' logic by not collecting pieces for their potential monetary value but for the joy the pieces bring to their lives. Their intention was never to build a collection; they just bought art they wanted to live with.

Many of the pieces are three-dimensional, but this is the best way to look at the collection as a whole. They are not just pieces of art in a vacuum, and they do not make sense unless you look at what's behind them: the ideas that went into creating the pieces, the artists and their stories, and a couple of art devotees from New York, stooped now with age, who selected each piece of art they own based on its meaning to them.

Herb and Dorothy love art—so much so that when the National Gallery of Art gave them a monetary donation, they promptly went out and bought more art, which they then gave to the National Gallery of Art.

"Herb and Dorothy: A Glimpse into their Extraordinary Collection" is on display at the Mississippi Museum of Art (380 S. Lamar St.) through Sept. 12. Call 601-960-1515.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID