Wednesday, November 4, 2009

On the evening of Oct. 27, the mayor of McComb, Miss., was in the city's board room, arguing with his city attorney about fractions. The mayor, Zach Patterson, wanted to block a vote to fire the city's accountant. The accountant had filed a grievance against a handful of city officials Oct. 13, and Patterson said that firing her without warning, in a public meeting, would look like retaliation. The city attorney, Wayne Dowdy, told him that he could not intervene in a motion approved by the majority of the board.

"Mr. Dowdy, first and foremost, you're incorrect," Patterson said. "If you read the charter and ordinances of the city of McComb, Mississippi, it says it requires a two-thirds vote (to fire), not a majority."

"And here, two-thirds of six is four," Dowdy replied.

"Two-thirds of seven is five," Patterson shot back. "And this is the Board of Mayor and Selectmen, if you want mathematics. So two-thirds of seven is five."

"Mr. Mayor, you do not have the right to vote," Dowdy insisted.

"And sir, as a former mayor and a former congressman, those days are over," Patterson said. "You're sitting here as the attorney of the city of McComb, so they say. And I say that it gets back to our mathematics quiz. Two-thirds of seven is five."

"Two-thirds of six, if it's committed to vote, is four," Dowdy said, his impatience audible. "I learned that in the first grade."

"What first grade did you attend? This is the Board of Mayor and Selectmenthat's seven members, sir. And the mayor votes in case of a tie."

"Only in case of a tie."

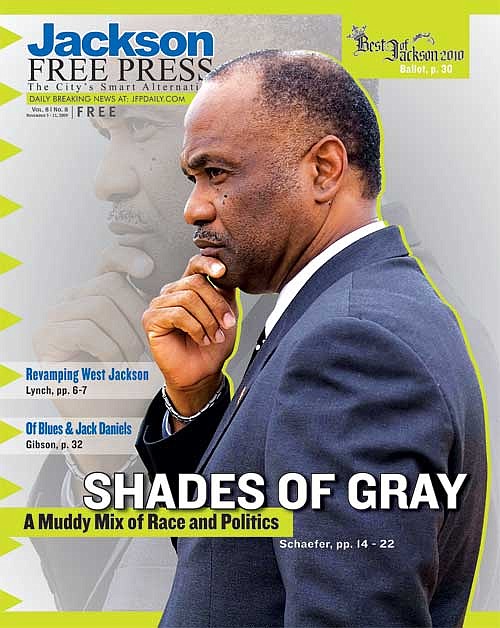

Patterson, the first black mayor in McComb's history, was wearing a slim charcoal suit with faint pinstripes and a red tie. Every meeting of the McComb board of mayor and selectman is videotaped, and Patterson seemed aware of his place at the center of the frame as he sparred with Dowdy. Dowdy, a former U.S. congressman, state representative and chairman of the Mississippi Democratic Party, was also mayor of McComb from 1978 to 1981, and he seemed determined to correct the mayor.

When Patterson declared that he would not preside over an open session on a personnel issue, Dowdy offered that state law did not require an executive session on personnel matters and only allowed for one.

"Mr. Dowdy are you done quoting the law?" Patterson said. "Once you quote the law to me, sir, then you wait, and I'll pull your chain later."

Many of the mayor's statements were echoed with murmurs of assent and laughter by the roughly 15 black supporters in the audience.

By most accounts, the Oct. 27 meeting was relatively calm. It was, however, the latest skirmish in a nearly three-year power struggle in McComb. On one side are the mayor and his supporters, who believe they're watching a dynamic black politician tied down by opposition that is rooted in historic racial inequality and racism. On the other side are a majority of the city board and a host of former city employees of both races who dismiss the charges of racism and see the conflict as a simple matter of executive overreach.

A Weak Mayor?

Zach Patterson drives a gray Mercury Marquis marked with his city title. He is the first mayor of McComb to drive a city vehicle, he proudly told me when I visited him in early October. Previous mayors treated the $18,000-a-year job as a part-time position and used their own transportation, he explained.

The mayor's opponents would say that the job used to be part-time for a reason. Unlike many other municipalities in the state, McComb operates under a special charter, which dates back to 1872. The city's founding document provides for a Board of Mayor and Selectman. Unlike under a mayor-council arrangement, however, McComb's system gives most powers to the six selectmen.

McComb's mayor can break a tie vote, recommend names to the board for department heads and preside over meetings. City employees serve at the will and pleasure of the board, not the mayor. Much of the day-to-day business of the city, such as administering contracts, hiring and firing city employees other than department heads, and preparing the budget, falls to the city administrator, a position appointed by the board.

Local attorney Norman Gillis, who is white, supported the mayor before his selection, but he now thinks the mayor has overstepped the bounds of his authority.

"They didn't want a strong mayor," Gillis said of the city's founders. "They wanted the power vested in elected officials who were representing the entire city."

Patterson has claimed that the charter is not clear on the mayor's weakness, however.

As justification, he points to a section in the city's book of ordinances that gives the mayor the power to "supervise all the officers of the city," "see that all law, ordinances and resolutions are enforced" and "suspend all delinquent officers or agents of city government."

Gillis maintains that section is a vestige of a brief period, from 1931 to 1947, when the city adopted a "mayor-commission" form of government. The city repealed the more extensive reading of the mayor's power in 1947 and again in 1969, Gillis says, when it adopted a new, modified form of the 1872 charter.

"Nonetheless, several old provisions reciting the mayor's supervisory authority under the 1931 mayor-commission charter can be found in today's outmoded ordinance record book," Gillis wrote in a Nov. 20, 2008, letter to the editor of the McComb Enterprise-Journal. "The failure to exclude these repealed ordinances from the printed code of ordinances is the source of the mayor's erroneous claim to full supervisory power."

As Gillis sees it, the mayor's mistaken "claim to full supervisory power" is behind the dizzying series of personnel shake-ups that has marked Patterson's term.

First to leave were a handful of city employees that Patterson inherited from his predecessor, Tommy Walman. Five city officials resigned during the first ten months of Patterson's term: Walman's city administrator, city clerk, fire chief, assistant police chief and visitors bureau director all left, citing various reasons. In September 2008, the city's longtime city attorney John "Bubber" White and Police Chief Billie Hughes retired.

Staff shake-ups often accompany a change in administration, but the turnover continued with Patterson's own appointments. The mayor's pick for fire chief lasted ten months before resigning in August 2008 amid questions about her qualifications. White's replacement for city attorney, Rachel Michel, lasted two months before Patterson replaced her. Michel returned in February 2009, when a four-member majority of the board rehired her. She resigned one month later, however, saying she could not work for the mayor. Patterson had made unreasonable demands, Michel said, such as insisting that she not communicate with board members outside of meetings and that she get his prior approval for any instructions she gave city employees.

The city board approved Patterson's recommended city administrator, Jim Storer, unanimously in March 2008, but in September of that year, a four-member majority voted to oust him for failing to communicate with them. Patterson refused to acknowledge Storer's firing and kept him in the position for two more months, until a letter from the state attorney general's office upheld the board's decision.

Hughes' replacement for police chief, Greg Martin, has had his own tumultuous relationship with the mayor. Three days after taking the job on an interim basis, Martin filed a grievance against Patterson with the Mississippi attorney general's office. Martin's grievances included six separate incidents in which he alleged that the mayor demanded police officers acknowledge him in public, tried to intervene in cases or asked for access to inmates. Patterson suspended Martin, but the board rehired him in February 2009 along with city attorney Michel. Martin's grievances against the mayor are still pending review from the attorney general, and Martin declined to comment on the issue.

On June 9, 2009, the board of selectmen voted 4-to-2 to make their weak mayor even weaker, by changing several city ordinances to strip Patterson of his supervisory authority over city employees and department heads. Since that move, the board has filled city postsincluding the city attorney and city administrator's positionswithout his approval or recommendation.

Patterson maintains that the board would have to amend the city charter to legally strip him of those powers, rather than simply pass a few ordinances.

"The changes in the ordinances, in the charter that they enactedI consider them to be unlawful," Patterson said. "And I conduct myself accordingly. I do not acknowledge any appointments or anything that they've made since they changed the charter."

On July 24, he filed a lawsuit against the four-member board majority, hoping to prevent the ordinances from taking effect after a 30-day notice period had expired. Patterson alleged violations of the Voting Rights Act and of his civil rights, along with many other charges, including harassment, libel, slander, conspiracy, fraud and abuse of power.

In August, a federal district court judge denied Patterson's request to stop the ordinances from taking effect, and Patterson's suit now awaits a hearing in November.

A New Day In McComb

Patterson says he spends most of his working days driving the streets of McComb. When I visited him, we spoke only briefly in his city hall office before he offered to show us around the city.

As we pulled out of the city parking lot in his car, Patterson received a call. He spoke for several minutes to the unidentified caller before hanging up, saying that he had guests. The call was a complaint that someone in the city was trying to get a traffic ticket fixed, he said.

Patterson's civil-rights rhetoric is not typical of a man with his resume. He spent 26 years in the U.S. military, graduated from the Army War College and worked for the American Cancer Society in Atlanta as its chief information officer. He credits his background with increasing his appeal to white residents.

"I've gone through all those predominantly white institutions," Patterson told me. "I understand the game, but I don't play it."

Patterson won the mayor's office in 2007 with 56 percent of the total vote. African Americans make up roughly 60 percent of McComb's population.

The first stop on our tour was the city's wastewater treatment facility, which is currently under construction. Patterson counts the project as one of the crowning achievements of his term. For years, the city has paid fines because its existing lagoon system for treating sewage fails environmental monitoring tests. The new facility is being built with a $34.5 million loan from the state Department of Environmental Quality, which Patterson hopes to pay off by securing wastewater treatment contracts with neighboring municipalities.

Patterson faced criticism over the project's cost, which ballooned from an original estimate of $20 million. He found himself on the opposite side of another public works project, a proposed $13 million fiber-optic network for the city. In June 2007, selectmen unanimously approved a contract with a Florida company that would have established a city-run network providing Internet, cable and television. The mayor refused to sign the contract, however, and the board eventually reversed its vote.

"I saved this city from its own peril and doom," Patterson told me. "It would've been a $13 million fiasco."

Computer penetration in the city is low, Patterson explained, and the city would risk losing out to private telecommunications companies.

"Why should we as the City of McComb get in a business that BellSouth is in, Cable One is in?" Patterson said. "I don't want to compete with my strategic partners."

From the wastewater treatment plant, Patterson drove to the traditionally black neighborhood of Beartown. Patterson diplomatically refers to this area and other historically black areas like Algiers and Burglund as "previously underserved," and they look the part. Some houses look well-maintained, their lawns groomed and front porches decorated. Others slump off their foundations. Abandoned homes dot the streets.

If you were black, Patterson said, "This is the side of town you were relegated to, even after the '60s."

Patterson has pushed for street repairs in these areas, but he sees places like Beartown as suffering from a lack of attention as much as resources.

"In Beartown, sometimes people bring trailers into the middle of neighborhoods, because there was no zoning enforced," Patterson said. "Once they're in, you have to grandfather them in, because they have such a financial investment, you can't get stuff out of there and begin building the community up. You create enemies when you say, 'This must go. you must improve this.'"

Still, Patterson believes he has won far more enemies for his attempts to improve racial parity. At the Oct. 27 board meeting, the city administrator delivered a report on another of Patterson's pet issues: long-term leases of city buildings that he calls "sweetheart deals." The city leases a handful of buildings at low rates, sometimes as low as $1 per year, to private organizations. Those organizations, which include the American Legion and the McComb Garden Club, are historically white, and some have had 50- or 90-year agreements with the city since the 1930s. After listening to the city administrator's report, Patterson spoke for 10 minutes about the leases, arguing that several attorney general opinions advise against leases longer than the term of a city's elected officials.

"It's an issue of equity and fair play," Patterson said. "We have to look back and see where the city was at that particular time, and make sure that all citizens had an opportunity to participate in such deals. I'll tell you, in 1934, all citizens of McComb, Mississippi, did not have the opportunity to participate. Not to go back and try and correct something from the past, but going forward we should be fair."

Patterson has a point.

McComb was a hotbed of civil-rights activism in the 1960s. In 1961, Bob Moses of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee led a voter registration effort in the city, which met with violent reactions from local Klansmen and law enforcement. When they were threatened with expulsion for participating, students led a walkout of the local high school.

A spate of church bombings in 1964, including more than a dozen in a two-month period, attracted national attention and briefly earned McComb the title of "bombing capital of the world."

In November 1964, the McComb Enterprise-Journal published a letter, signed by 600 white citizens, denouncing "extremists" and calling for peace and a "responsible" approach to the city's racial problems. The letter appealed to pragmatic business owners concerned for their livelihood, but it also earned the city praise from national press. Attorney Norman Gillis was one of the 600 white citizens who signed the letter.

'J.R. Ewing of McComb'

"Patterson's got more potential than anybody I ever saw, and he's really screwed it up," Norman Gillis told me. "I thought he'd make a hell of a senator when he first ran for office, but he proved he's actually on the verge of dangerous."

Gillis' opinion can weigh heavily in McComb. Selectman E.C. Nobles, the one black selectman to side against the mayor, called him "the J.R. Ewing of McComb," referring to the rapacious oil baron from TV's "Dallas." An attorney, Gillis' office spans most of a block on 21st Street. In addition to his law practice, Gillis owns a shopping center and was an original board member of the Southwest Mississippi Regional Medical Center, a primary employer and economic engine for the city.

"I supported the mayor; I worked my butt off," Gillis said. "I persuaded a lot of people: 'Look this guy's got a lot. He's good-looking, he's articulate, he's well-educated, he comes from McComb, he's been a military guy. He will bring us peace and harmony because of his ability as a speaker and as a personality.'"

The attorney still has a "Vote Zach Patterson" button. But Gillis said that his opinion of the mayor turned negative when it became clear to him that Patterson was trying to shoulder more authority than was legally his.

"McComb has always been a happy, prosperous, good, fine place to live," Gillis said. "It was only when we had a conflict between the aspirations or assumptions of a 'strong mayor' and the constitutional basis for government" that things turned bad."

The mayor's supporters believe Gillis has more to do with the mayor/board feud than he lets on. Chief Financial Officer Mary Adams, a Patterson loyalist, compares Gillis to the Wizard of Oz.

Since losing confidence in the mayor, Gillis has taken positions that put him on the other side. When Patterson questioned the residency of a white selectman, Danny Esch, Gillis represented Esch. In his November 2008 letter to the Enterprise Journal, Gillis called on the board to request "an injunction to restrain the mayor's continuing breach of his oath of office." And this June, when the board majority approved the ordinance amendments that stripped Patterson's power to supervise city employees, Gillis notarized the legal notice that accompanied the ordinance changes.

To Patterson, these stances confirm Gillis' place in the white "good old boys network." Patterson says that Gillis soured on him when he refused to take advice from the attorney outside public meetings. Since then, Patterson believes, Gillis has tried to shape city policy by orchestrating the opposition efforts by the white selectmen.

"He's the lead guy," Patterson told me. "They are puppets of him."

Gillis scoffs at the mayor's accusations and says that opposition to Patterson has nothing to do with race.

"McComb went through hell in the '60s, but we came out of that with about as good a community feeling as you could possibly want between the races, to the extent that that's at all possible," Gillis said. "Every municipality in Pike County is black, and there's a certain amount of resentment in some places, but I think it's more on the black side than the white side."

"And now the mayor's chief opponent is a black guy, E.C. Nobles," he added.

'High-Tech Lynching'?

To hear Patterson's supporters tell it, Ernest "E.C." Nobles has betrayed McComb's black citizens. Nobles frequently votes with the white selectmen and in June cast the critical fourth vote in favor of the charter-amending ordinances.

It's an especially loaded charge considering Nobles' background. His family's business, Nobles Bros. Cleaners, served as an unofficial headquarters of black resistance during the 1960s.

E.C.'s father, also named Ernest, once hid Bob Mosesdirector of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's Mississippi projectin a pile of clothes when armed whites were looking for him. In 1965, the business was firebombed, and E.C. proudly points out the charred rafters that his family has chosen not to replace.

Nobles won a seat on the board of selectmen in May 2008, after a lengthy and ultimately successful campaign, led by Norman Gillis, to unseat his predecessor, state Rep. David Myers. In March 2008, the U.S. Justice Department agreed with Gillis that Myers could not hold his state and local offices simultaneously.

Four days after Nobles' win, the board held its first meeting, and Nobles found himself thrust in the middle of the growing feud between the mayor and board.

The three white selectmenDanny Esch, Bob Maddox and Wade Lambcalled for a hearing on Patterson's residency in McComb. They had some cause for concern: Patterson did not file for homestead exemption in McComb until January 2007, despite having moved back from Atlanta back in 2005.

Nobles decided that he did not know enough about the residency spat and abstained from voting on Patterson's hearing. The measure passed 3-to-2, with Nobles' abstention giving the white selectmen an edge. Patterson later referred to the vote as a "high-tech lynching."

The mayor's supporters were furious.

"Everybody immediately thought that I had gotten in bed with the other selectmen," Nobles told me.

On the Friday after the meeting, he received a visit.

"There was a contingency of men come here and tell me I need to vote in a bloc with the black men," Nobles said.

"And they want to tell me I need to vote with the rest of the (black) selectmen because it's a black thing. I'm not going to vote for nothing that I don't feel I need to vote for. I'm my own man."

The following Sunday, a group of roughly 10 protesters congregated outside Nobles Bros. Cleaners, carrying signs that read, "EC 4 SALE HERE" and "WHO OWNS U."

"These people were saying they were paid to do this," Nobles said. "They said they were being paid $10 an hour to hold these signs. And these are not people that were your run-of-the-mill people. Some of these people were down-on-their-luck type people. They may have been just out of jail or transients. They couldn't tell you why they were holding those signs."

Since the protest, Nobles has only grown firmer in his opposition to the mayor. He objects to Patterson's firing of 10 city employees. He worries that Patterson interferes too much with police operations. And he scoffs at the argument that Patterson is simply encountering resistance because he is black. Most of the city officials that the board has placed over Patterson's objections have been black, he notes. That includes the city administrator, fire chief, police chief and personnel director.

"All of these people have lived in Pike County all of our lives," Nobles said. "The only time any of them left was for educational purposes. And the mayor has been gone for 35 years, then decides to come back and talk about how we need more black representation. Well, heck man, before you got here, we had a black fire chief, black personnel director, black deputy director of public works. All of this was here before you got here. I can't see where you can say that this is racist."

The Mayor's Allies

On the other side of Summit Street, Bullock's Washeteria hosted a community meeting in response to Nobles' abstention on the residency issue. Sherry Robinson, whose father owns Bullock's, said that she believes the selectman is bending to influence from the white selectmen.

"My impression of him is he's a young guy who's being told what to do," Robinson said. "He's voting as he's told. He's not voting for the people who elected him."

Eddie Smith has another theory. He admits to being one of the three men who approached Nobles about the residency issue but says that they were seeking an explanation, not a commitment.

"Myself and two other guys went to talk to Mr. Nobles about his vote because we didn't think it was fair; it was against the dictates of the black community," Smith said. "He says 'Hold it, that man has devastated my family, and I'm going to overturn everything he's done.'"

Nobles disputes Smith's account, though.

"Why would you go with three people to ask someone about how they voted unless you were going to strong-arm them?" Nobles asked.

Police Chief Greg Martin and former Assistant Police Chief Perry Ashley are both relatives of Nobles, but the selectmen denies feeling any enmity toward Patterson for their troubled relationships with the mayor.

Smith, a native of Bogalusa, La., moved to McComb from Milwaukee, Wis., in 1995. At city meetings he speaks in Patterson's support when the board invites public comment and raises his hand, as if in a classroom, for permission to interject, when it does not. For Smith, Patterson represented a change of attitude as much as a change in the city's racial dynamics.

"I was so happy when I saw him come," Smith said. "Not only because he was a black mayor, but because at his inauguration speech he said: 'I want you to get off the wagon and pull. We're going to make McComb an ideal city for everybody to live in.' It was so uplifting to hear him say that, that it was going to be different. And this is how it turned out. He had a good program, some good people working for him, and they just destroyed it, all the unity."

For 15 years, Smith has lobbied the city to pave a street in the Beartown neighborhood. Patterson has joined Smith's effort, twice calling on board members to find the money to pave the street. But Smith now sees Patterson as having his hands tied.

"I'm not very optimistic," Smith said. "Any time you can find some articles to strip the mayor of his power, the power that we voted for, then it seems to me you can do anything. Everything has to be done at the will of these four selectmen. So I'm not really optimistic. I know if the mayor had an opportunity to change things, he would."

The Price of Loyalty

Chief Financial Officer Mary Adams is a small white woman with a big complaint. On Oct. 13, she filed a list of grievances with the city, alleging harassment from the majority of selectmen, city administrator and city attorney. When I asked to speak with her outside City Hall, she led me into her office and closed the door, as if to avoid eavesdroppers. Wearing a denim jacket and matching blue jeans, she explained in a hushed voice why she thinks Patterson has run into such fervent opposition.

"Race," she says matter of factly, drawling the word out into two syllables. "Because Mayor Patterson is a black man and a forceful, dynamic personality."

Adams' own quarrel with the board began after the four-member majority voted in June to revoke Patterson's powers of supervision. On July 1, she clashed with Selectmen Nobles, Maddox and Lamb, when she instructed the city clerk not to sign documents coming from the four-member bloc without her permission.

Since that time, Adams claims, the four selectmen, along with city attorney Dowdy and the current city administrator, Quordiniah Lockley, have tried to make her job harder and force her resignation. Lockley denied her the authority to correct the city's books, Adams says, and in response she has refused to sign off on the city's expenditures and other documents.

Lockley was laid off from the McComb Public Works Department by the man he later replaced, former city administrator Jim Storer. This gave Lockley a grudge against the mayor that the four-member board majority exploited, Adams believes.

He filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the city after being laid off but had the complaint dismissed after his July 28 appointment as city administrator, she points out.

"You could see him on their side," Adams said.

Charles Ashley owns Ashley's Body Shop on Presley Boulevard. He has a penchant for richly colored dress shirts, with the top button unbuttoned, and he wears his hair in shoulder-length braids.

Ashley is one of the mayor's most vocal supporters and a fixture at board meetings.

"There's not a reality TV show better than this," he said of McComb's board meetings when I spoke to him at his shop.

Ashley peppers his comments on the city with phrases that Patterson also uses, accusing the white selectmen of holding "meetings before the meeting." An ex-convict who served eight years in prison, Ashley largely ignored politics until Patterson's candidacy and voted for the first time in 2007.

"I'm one of those people who didn't understand some of this stuff until he got into office," Ashley said.

Ashley co-publishes the Mississippi Tribune, a weekly newspaper directed at McComb's African American community.

The newspaper arose out of widespread frustration with the Enterprise-Journal, the local newspaper. Ashley, like many of the mayor's supporters, believes the white-owned and predominantly white-staffed paper is biased against the mayor, ignoring his accomplishments and attempting to sway public opinion against him.

Patterson himself has made the same accusation. When the Enterprise-Journal sued the city for an open-meetings violation in 2007, he accused the newspaper of trying to influence him.

Ashley also serves on the board of PEERS (Preventive Entry and Ex-Offender Re-entry Services), the mayor's initiative to help ex-convicts find jobs and re-enter society. The private initiative pays for transitional housing and tries to change ex-convicts' behavior by connecting them with church groups.

All the program's costs come out of the leaders' pockets, Ashley said.

"The board could vote to take care of PEERS, but because the mayor started it, we already know it's going to lose 4-2," Ashley said.

Ashley drove me to the warehouse where he stores old Mississippi Tribune copies. He handed me issue after issue, all blaring positive news about the mayor's efforts: "Current mayor accomplishing more than previous mayors," "Mayor solves water problem and moves city forward," "Selectmen appear to be violating several laws."

Then we drove back to his shop, with the sky threatening rain.

"Malcolm X and Martin Luther Kingthey had people standing arm in arm with them," Ashley told me as he parked.

"When he walks down the street, he's alone," he said of Patterson.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID