Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Wyatt Waters unfolds the legs on his handmade wooden easel and sits down to paint a neighborhood scene in Belhaven. He is on one of those tree-lined streets with historic homes, neat lawns and attentive homeowners. He has paper, paints and water, everything he needs to capture the character of this random block.

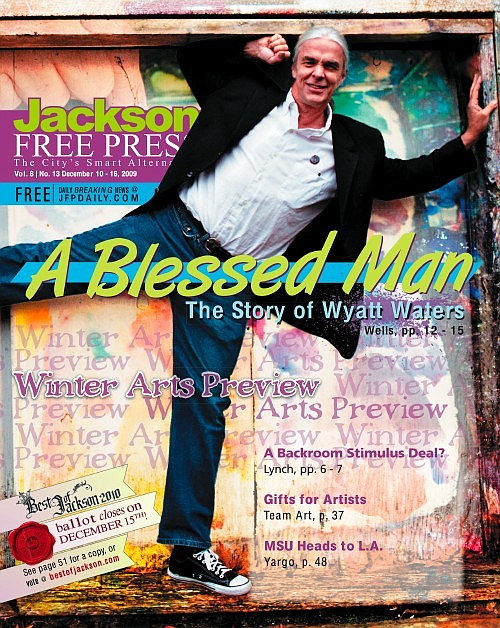

Waters does this a lot. He paints in the open air, capturing scenes around Jackson and all over Mississippi. He is a watercolor master who works on location, and recipient of a 2010 Governor's Award for his body of work. Waters frequently does a series of paintings of a town like Vicksburg or an area of Jackson such as Fondren. On this particular day, he is working on his Belhaven series.

A woman comes out of the house in front of Waters' easel to confront the stranger.

"We don't need any painters. We have plenty of painters right here," she tells him.

Waters doesn't shoo easily. A car pulls into another house on the same block. A man and woman get out of the car, looking concerned. The man ushers the woman into the house, then comes over to the artist.

After exchanging hellos, the man gets serious. "What's your business here today?" he asks Waters, who explains who he is and what he is doing.

"You can't be. Wyatt Waters is a much older man."

It turns out the couple has a Wyatt Waters book in their house, so they consult it and examine the photograph and realize that the relaxed, tall guy from Clinton with a gray ponytail who he says he is and is probably not planning to rob them blind.

Waters doesn't hold it against Belhaven. He understands a lot of folks don't always get what he's doing or the way he does it. He also appreciates that many people think of art as something that must be stapled on canvases or something using fringe objectsoften bizarre and uglyand funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. They don't always think of art as an everyday part of life.

"I'm frequently the only artist they've seen working outside," he says. "People think that art is something that only happens far away."

He lives his life with the attitude that art is for everybody. His scenes are familiargourds turned into purple martin houses, leaves burning in a ditch, vibrant day lilies, old motel signs, front porches, watermelon, iced teahe paints images of home.

Some refer to his work as nostalgic because it takes them back to childhood memories of loving grandparents and a cozy, happy Mississippi. Waters doesn't see his work that way. For him, he's not recreating something from the past. He's documenting the here and now.

Everything He Needs

Downtown Clinton's Jefferson Street in late November is beyond charming. The leaves have turned luminescent shades of red, gold, orange and yellow with some twinges of green and brown. The brick streets, the small shops selling antiques and books, the hanging plants invite visitors to walk slowly and window shop. Music wafts up from sidewalk-level speakers.

Two bright yellow bicycles lean against a storefront under an awning. This is the Wyatt Waters Gallery.

The door is propped wide open to let in the mild fall air. On the walls inside are framed watercolors so vivid, so intense, they light up the room. Waters looks at a mammoth Christmas wreath his 23-year-old daughter, Crimson, made and contemplates the layout for the toy train he plans to put up for display in the window.

Waters, 54, has lived in Clinton since he was in 10th grade. After high school, he went on to Mississippi College. He stayed there and got a masters degree in art.

Over the years, he started a family, opened a studio gallery, became a town leader. He only left Clinton once, briefly, as an artist-in-residence in the Lauderdale County schools. That was early in his career, and he returned home after a short stint.

"I don't have anything against going away. But everything I need is here," he says.

Sure, people told him that if he wanted to be a serious artist maybe he should go study somewhere else. His mentor, Sam Gore, was not one of those people.

Gore taught Waters his first college course in watercolor painting at 8 a.m. Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays when Waters was a sophomore at Mississippi College, just blocks away from Jefferson Street. Gore recognized the talent immediately.

Gore, 82 and in his 58th year of teaching at Mississippi College, stops by the gallery the day Waters is admiring the massive Christmas wreath to congratulate Waters for winning a Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts. Gore, a sculptor, won this award himself in 1997. The professor couldn't be prouder of his former student.

"He didn't have to go to New York or Saskatchewan. He got the fundamentals in school," Gore says. Waters concentrated on mastery the way a pianist who has clocked 10,000 practice hours becomes a master of his art. Gore is still impressed with the hours and paintings Waters has put into his craft: "He was painting early in the morning, early in the evening. Most people are slow-poking."

Waters recalls painting 100 paintings that first semester of Gore's class because his professor had said if one wanted to be good, that's the thing to do.

"He worked hard for this," Gore says.

"He made me work," Waters adds.

Painting to Find Out

Waters paints on location when the light is right and where the moment lingers. He's done about a dozen paintings in the past two weeks. One of these is of a tree surgeon cutting down a large tree. The sawdust was in the air when he painted the scene, and some of it might even be here in the painting. He worked on the figure of the man belted to the tree trunk and sawing first, capturing the transitory movements that might end soon. Then he worked in the stumps of the tree limbs and then the background.

It might have been easier for someone else to snap a photograph of the unexpected scene and save it to paint another day. Waters doesn't work like that. He has a problem with a digital society that leaves people unconnected with nature. Yet he doesn't want anyone to think he's a modern anarchist or an antiquarian. He keeps his cell phone with him at all times and is updating his Web page. He just thinks much is lost to those who only live on Facebook.

Too many Mississippians are cut off from the seasons, he finds. "We live in a centrally heated and cooled time. You want to know it's summer in summer," he says.

The painting process deepens Waters' experience with his environment. He studies the scene before him and can get lost in its beauty, even when it's something ugly like rusty tractors clearing a muddy lot. Waters paints to clarify his vision. When he loads a brush with paint, he often loses track of time.

"I paint to find out. Painting is a way to get in that frame of mind," he said. "When I get in the zone, that's when the expressive thing happens."

Collectors noticed Waters years ago and started buying his original works as well as prints. When he started out as a working artist in his 20s, he painted portraits of passersby for $7.50. He got to the point where he could do four in an hour, making a nice hourly income for a struggling artist in the 1970s.

To get his name known in the Jackson area, Waters started painting pictures in downtown Jackson, setting up his easel to paint old buildings being demolished and replaced, "staying ahead of the wrecking ball." He created vibrant, fresh records of these disappearing sites. And he started to make a name for himself, even as many Jacksonians crossed the street to avoid a long-haired man they assumed must be homeless and panhandling. Police urged him to move along. Even though the law was on his side, Waters found it easier to move along and paint another day.

But he never went far. He never moved out of state. Instead, Waters dug his heels in. He led revitalization efforts in Clinton. He bought a building downtown in the 1980s, and encouraged others to set up shop on the brick streets of Olde Town, the heart of Clinton behind the strip malls and residential streets.

Artists get into revitalization for two reasons, Waters theorizes. Distressed downtown spaces are usually the most affordable places for struggling artists to work and live. And it's artists who often have the vision to see what is possible with a blank downtown and create new realities.

Tara Lytal, director of Main Street Clinton, says Waters' presence in the downtown can't be underestimated.

"Wyatt was here before others. He made an investment. He was passionate," she says.

Not only did Waters help revitalize Clinton years ago, he has an economic impact on the town today. "He brings in people from all over the country," Lytal says. Also, with all his travels, he's an ambassador for the community."

When he returns from his travels, he brings back ideas he wants to implement at home. He likes communities with WiFi, bicycles, outdoor music, recycling.

Waters now serves on the all-volunteer board of directors of Main Street Clinton, an organization started three years ago to preserve and promote the downtown. He's thinking about how to attract a pizza restaurant to the Olde Town district.

He has ideas.

The Way It Is

Vicki Waters, the wife of the artist, sits at the counter with a scented candle, her face as lit up as her husband's watercolors on the gallery's walls. She counts round Christmas ornaments in boxes destined for Square Books in Oxford. The showcase under the counter displays coffee cups, mouse pads, coasters, chunky rings, bars of soap, tote bags. All these items have Waters' art printed on them. Note cards, post cards, calendars and books are also for sale. Anyone can buy art at this gallerypostcards only cost $1, while some of the framed originals run thousands of dollars.

A well-dressed woman comes into the gallery. She had just called a few minutes earlier trying to find the location. Sabrina Krouse of Nashville, Tenn., has come to pick up an original print. Vicki Waters' eyes shine with recognition.

"She is one of our best customers!" she says warmly.

Krouse has been here before, years ago, but she has sent numerous other customers to the Waters gallery. On this day, she is at the gallery to pick up a watercolor painting of the Dixiana Inn in Vicksburg. She stands with Wyatt and Vicki Waters in the middle of the gallery looking at the painting for a few silent moments.

"He just depicts Mississippi the way it is," Krouse says. She grew up in the Jackson area.

Waters gets a brush and signs the Dixiana painting he finished years ago. "I'm just going to put my last name," he says. He holds it out for a moment. It dries quickly. He has about 1,400 paintings in the gallery, most of them unsigned.

Krouse starts talking about his other paintings she loves. Elephant ear plants by a front porch dominate one of them. Vicki Waters sits cross-legged on the floor and pulls open wide, flat drawers full of paintings. She's looking for the elephant-ears painting. She turns up a potential candidate, but none of them is sure it's the one.

After Krouse leaves with her Dixiana painting, other customers wander in to look around or to say, "hi." A schoolteacher in an Ole Miss sweatshirt buys a $100 print called "Bankers Hours." It's a watercolor of men fishing at the Ross Barnett Reservoir with seagulls overhead. Waters said the seagulls got blown in by Hurricane Camille and never left.

The intense bright colors in Waters' paintings are so sharp, so clear that street scenes look unpolluted. The sidewalks are cleaner and the flowers brighter. Thin layers of purple, green, yellow and red all glow like stained glass. The heavy white paper he uses acts as a second light source, bouncing pure color back at the viewer.

Waters uses a specific paper imported from a French company founded in 1492. It's heavy paper500 sheets of it weigh 140 pounds. It's made of rag and flax. Hundreds of years ago, this same company made the special paper out of the fabric used for ships' sails.

Many of his paintings have spots of purple that make the whole image pop off the page. Purple, Waters said, doesn't occur that often in nature. He becomes so engrossed in his painting that after a while he begins to see colors that may not be there at first glance. It's like staring at a red dot, then looking away to a blank wall and seeing a round green light. Color saturates retinas so that eyes see the opposite color.

On Life and Love

Waters' talent isn't confined to painting. He also writes and performs music with his band, Waters Edge. They used to play in clubs around Jackson, and they have put out two albums. More venues and more CDS are in the works," he says. They do not like to do cover songs. Waters can't stand Southern bands that play "Free bird" and "Brown-Eyed Girl" relentlessly. He really wants to spend more time with his band, writing new original music and lyrics. He misses it a lot.

The album "Record Player" is full of pleasant surprises. Some songs are slow, some are fast. Laid-back, jazz-infused tunes tell stories of being true to yourself. Lyrics include a look at his in-the-zone painting style:

"I know the way to make a painting fly

Is when I paint like I didn't try."

Songs with slight hints of funk, country and blues express much of Waters' take on life and love. In the song track, "Real Man," Waters sings:

"Make me a mystery

Paint question marks all over me

I'm just a real man

I'm not that different from the other guys

You think you know."

Waters observes in the song "Buckminster Fuller" how modern life turns out not to be what was predicted in Popular Science in the 1960s. "We turned into the parents we adore," he sings, then, "Our neo homes, no geo domes."

'Don't Flip the World Off'

Waters grew up in a family of athletes. His father was a high school coach who had been a star football player for Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). Two uncles played professional baseball. His older brother Jim was a quarterback. All these athletes encouraged Waters in his art. "They embraced me," he says.

Growing up, Waters was bored to tears at times. "Go do something," his family challenged.

His "something to do" was art. He drew. His mother saw to it that he got extra art classes.

Art is a solitary activity, and artists get into art precisely because it is solitary, Waters says. Artists compete with themselves. That was how he preferred to compete: When it came time for him to choose a sport, he chose track because it was something he could do by himself.

He was shy and self-conscious in high school, especially after moving from Florence to Clinton. Every once in a while, he still bumps into an old high school acquaintance who recalls taking art class with him. The problem is, Waters didn't take any art classes in high school. He felt that awkward in his own skin. But people have an odd way of remembering things.

One thing Waters clearly remembers from the time when his dad was a high school coach in Florence. Some racists burned a cross on his family's lawn after the schools were integrated. He knew a lot of good people in Florence, and most them wouldn't have done that, he says.

Growing up, he watched the national media portray the South in terms of extreme racial division.

"I knew the negative things. I've seen things change tremendously. We have a long way to go. Everybody does," Waters says.

Back in the 1970s, Mississippi artist Marie Hull told Waters he needed a European experience. It didn't seem possible until Waters was teaching a night class at Mississippi College. A different type of student took night classes, he learned. These were adults looking for professional certification or personal betterment. One of these adults, John Flood, offered to send Waters to Paris, France, for two weeks. Waters went and had his European experience, taking in the galleries and museums.

"It had a huge impact," he says. "It helped direct me. I realized the things I really wanted to paint were where I lived."

He had other opportunities to travel for art's sake. He and Gore went to Washington, D.C., when the older man had an exhibit there.

Waters visited the National Gallery of Art on that trip. As he always does when he travels, he took ideas back home.

His influences vary from Edward Hopper's realism to Vincent Van Gogh's vibrancy. He's fond of Ashcan School art. The artist he quotes, though, is the Mississippi Gulf Coast eccentric, Walter Anderson.

Not only was Anderson a talented and trained artist, he had a practical view of making a living as an artist.

"Walter Anderson said there was art he does for the public and art he does for himself," Waters says. "For him, the thing was to be self-supporting, financially independent. You don't want to be so aware of (making money) that it gets in the way."

Even now that many consider Waters successful, he and Vicki still live in the same small modest house and drive used cars. One day, the couple were sitting on their front porch when two people walked by their house. Some bushes blocked the Waters from view, but they could hear the couple on the sidewalk debating about whether or not this was really where Wyatt Waters lived. It amused Vicki. Where did people expect them to live?

People have asked Waters to paint a specific subject for them. If the subject feels right to him, he will paint the picture as a work for hire. He offers the person requesting the painting the first chance to buy it. If they don't like it, they don't have to buy it. He doesn't do commissions. The duality of making a living while keeping true to his art is an everyday reality. It's about having a good life and working toward a better life while keeping clarity. It's being honest.

"Honesty is what I admire. There's so many ways you can be honest and so many levels," he says. "You can smell when people aren't being honest."

"I'd much rather see you paint what you want to paint," Vicki Waters says.

"It's a balancing act," he says. "Don't flip the world off. Don't suck up to the world. Be yourself."

Artists have a self-deprecating joke about becoming commercially successful that Waters shares: If everybody likes it, what's wrong with it?

'Blessed with Talents'

George Ewing went to school with Waters' younger brother Joel. When they were in grade school, Wyatt Waters was in high school. The first time Ewing realized that Waters was a talented artist came years later, in the early 1980s, when Waters painted a downtown Clinton scene for a festival poster. It was a scene on Jefferson Street, where Ewing's mother worked. Today, Ewing is president of the Arts Council of Clinton and one of the people who nominated Waters for the Governor's Award.

"He's a hometown boy blessed with talents. His artwork is world renowned. He could go anywhere," Ewing says. He counts among Waters' accomplishments his professional achievements and personal kindness: Waters supports other artists, belongs to various associations, does volunteer work, is loving and giving. And at Halloween, Ewing reports, Waters dresses up like a ghoul.

Back at his gallery, Waters picks up an unframed painting among lots of paintings lying around the gallery. This is one he did not create. His 3-year-old grandson made some bold strokes on a piece of the heavy, white paper, resulting in a minimalist abstract. Waters is proud. He's created a happy life.

"I want my grandson to live here and have the same opportunity as elsewhere. Opportunity is something you have to make. We can do so much more than we think we can," he says. He offers some plain advice for young creative types trying to make it without leaving the state: Be honest. Don't worry. Work hard. Don't quit.

"When everyone else quits, it leaves the field wide open," he says.

The Mississippi Arts Commission and state officials will honor Wyatt Waters, Lenagene Waldrup, the Grass Roots Radio Show, Bessie Johnson and David "Honeyboy" Edwards with Governor's Awards for Excellence in the Arts at a ceremony at 1 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 2, at Galloway United Methodist Church in downtown Jackson.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID