Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Kaleidoscopes are usually made from simple, cheap and seemingly random ingredients: a cardboard tube or two, colored pebbles or painted rice grains and a few cut-rate mirrors. That's it, really. You could buy everything you need to make one at a dollar store. The ingredients are inexpensive, maybe even shoddy. It's only when you look inside the kaleidoscope that it becomes strange, rearranging all that cheap bric-a-brac into something orderly and beautiful.

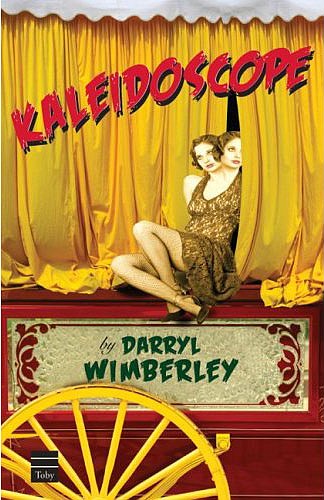

In his new mystery novel "Kaleidoscope" (Toby Press, 2008, $24.95), Darryl Wimberley tries to make a literary version of the instrument. The book assembles elements from genre clichésdime-novel mysteries, serial-killer crime fiction, gangster tales, film noirand filters them through the prism of carnival life.

It's 1929 in Cincinnati, and Jack Romaine is down on his luck. A low-stakes gambler with a drinking problem, he runs afoul of mob boss Oliver Bladehorn. To borrow from "The Godfather," as Wimberley does, the gangster makes Jack an offer he can't refuse: Find some of Bladehorn's stolen money and stocks, or else. To make things worse, Bladehorn casually reveals that Jack will have competition. "Fellow used to work for me," he says. "Arno Becker. Very unusual man. Very disturbed."

You can practically hear the minor chords. Indeed, Becker is disturbed, but in the cold-blooded, calculating way that exists only in cheap thrillers. Although he causes a lot of bloody messes, Becker never comes alive as a villain. He's a contraption, not a charactera combination of every methodical serial-killer cliché from Jason Voorhies to Hannibal Lecter.

For that matter, none of the book's characters feels like more than archetypes for the first third of the book. Early on, Wimberley writes that "about the only thing (Jack) had, really, was a movie star's face and physique. Marquee looks, the girls of Gilberts' said."

Indeed, at first, every character in "Kaleidoscope" feels like a movie cliché; it's worth noting that the novel began its life as a screenplay.

For all this hackneyed plot, though, Wimberley is a skilled writer of atmosphere. The dialogue is brisk and natural, even though it's laden with 1920s slang. He sprinkles tidbits about the timesthe books being read, how the Reds are doing that season, the women's flapper dresses, the politics of the erain a nonchalant, unobtrusive way. The Cincinnati he conjures is engaging without being cloying. The coming stock market crash is hinted at throughout the novel, but Wimberley doesn't overuse details or over-emphasize the research he must have done.

It's that atmosphere, not the plot, that enriches "Kaleidoscope," and gradually provides the characters complexity and depth. About a third of the way into the novel, Jack finds himself in Tampa, Fla. The money trail leads to an off-season carnival community, Kaleidoscope, run by a blue-skinned woman and an assortment of "freaks." Among the inhabitants are dwarfs, a man with a grotesquely oversized scrotum, Siamese twins and a 500-pound woman.

Just as kaleidoscopes rearrange what we once thought was normal, so too, the novel mucks up our perceptions. As Jack moves in under false pretenses, it is he who becomes the freak. After all, he's the only one without physical abnormalities or strange skills. So, no one at Kaleidoscope trusts him initially. He quickly learns that he can't judge people by their outward appearances. At one point, he calls someone a "n*gger," which would have been common in Cincinnati in the 20s, but the people of Kaleidoscope harshly rebuke him.

For the first time, Jack is forced to earn respect instead of taking it for granted. He learns to view society at a cockeyed glance, as if he were an alien observing America's strangeness through fresh eyes.

It's in this world that Jack begins to redeem himself, and where "Kaleidoscope" shifts outside cliché to become moving. The characters become more vivid. Sure, the mystery plot engine continues to chug along, but this carnival world is so rich and involving that it overtakes the stereotypes. As Jack digs for leads about Bladehorn's money, he instead digs into his soul and that of a community he never expected to love.

Hollywood cliché returns to "Kaleidoscope" at the end, and everything resolves itself too tidily and with too much action-movie nonsense. But the carnival residue sticks to Jack and to the novel. For roughly 200 pages, Wimberley dares to imagine an alternate, freaky and lovable environment that's unbound by genre. I wish the whole book had been like this.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID