Wednesday, August 6, 2008

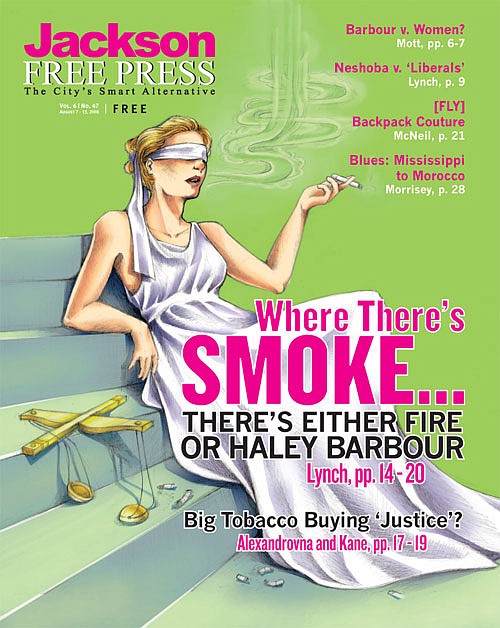

During his long tenure in Washington, D.C., Haley Barbour was known for his love of Maker's Mark bourbon, good cigars and Republican politics, not necessarily in that order. The Yazoo City native who became one of the most powerful lobbyists in the worldrepresenting clients from Big Tobacco companies to the country of Serbiapeddled a lot of influence amid the aroma of juicy steaks and cigar smoke in The Caucus Room, the restaurant/bar he helped finance with a bipartisan group of shareholders, including Democratic lobbyist Tom Boggs.

His work in Washington, though, was anything but bipartisan. But it was lucrative.

Barbour, a former lobbyist and Republican National Committee chairman, was instrumental in the formulation of the K Street Project in 1991, a crusade to assimilate conservative politicians with lockstep agendas, such as deregulation, and marry them with reliable corporate donors. The movement, which was a sharp contrast to previous years when lobbyists tended to work with members of either political parties, gave donors easy access to Congress and, according to some Washington lobbyists, created an environment of exclusion against some lobbyists who found themselves classified as "progressive" or "liberal."

The K Street Project, tied to former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich's "Contract With America," paved the way for the massive Republican takeover of Congress in the 1990s, which only faded as recently as 2006.

Tobacco money funded much of that movement, and part of Barbour's fortune. Barbour's Washington firm, Barbour, Griffith & Rogers, got almost $2 million from all four major tobacco companies in 1997 alone. It was regularly getting money at $140,000 a pop in 1999 from firms like Phillip Morris Companies, and Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corp.

When Barbour rode into the state governor's seat in 2003, he brought with him an incredible pile of influence still smouldering from his cozy relationship with the nation's largest tobacco companiesa relationship that seems to hold more sway over his decision as governor than do the opinions of Mississippi voters, even of his own party.

Barbour, with his trusty speed-dial connection to the White House and Republican congressional leadership, was able to twist considerable federal assistance for Mississippi in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. But local representatives say Barbour remains, first and foremost, a lobbyist–particularly regarding his precious tobacco companies, which have gotten a free ride from a governor who will not raise tobacco taxes, regardless of how many constituents of both parties consistently tell pollsters they want an increase.

"He's never stopped being a lobbyist," said Rep. Steve Holland, D-Plantersville, one of Barbour's most outspoken critics in the Mississippi House. "He never really put that load down when he walked into the governor's office."

It was quite a load to drop.

Changing Jobs

Barbour claims he is no longer a lobbyist, tobacco or otherwise, although information leaked to Bloomberg News during the height of his 2007 re-election campaign showed he still receives money from his 1275 Pennsylvania Ave. firm, which still represents tobacco clients.

The money is deposited into a "blind trust," which effectively protects it from information requests showing the public what corporate money is funding the lobbying firm's disbursement to Barbour's account.

Earlier this year, the governor signed into law a bill that included regulations for blind trusts. An outcry against political influence, triggered in part by state corruption indictments and Democratic demands for more clarity regarding Barbour's blind trust and his devotion to the tobacco industry, drove the bill to his desk.

After Barbour signed the bill, however, his attorney, Ed Brunini, asked the Mississippi Ethics Commission not to immediately adopt the new laws, arguing that information in Barbour's trust was never intended to be public.

Some commissioners doubt keeping the information hidden under the new state law is legal, and will be considering Brunini's request in the next few days.

Despite his claims of dropping lobbying ties, the governor has been willing to risk a serious slap to his opinion polls for the sake of keeping the state's 18-cents-per-pack excise tax on tobacco the second lowest in the nation. Barbour entered the political fray in the state Capitol in 2004, just in time to do battle with a flurry of attempts to increase state revenue through a cigarette-tax increase.

Democrats in the House attempted to merge the tax increase with budget balancing, such as the House's 2005 proposal to link increased tobacco taxes with a decrease in Medicaid costsa swap of sorts that opinion polls show is popular with both state Democrats and Republicans.

Barbour used the conservative mantra "no new taxes" to defend his opposition to the popular hike, and convinced Republicans and conservative Democrats to effectively take up the call.

When Democrats tried to make the tax-increase revenue-neutral, linking it with a decrease in the state's 7-percent tax on groceries–the highest of any state in the nation–Barbour clung to the argument that the grocery tax cut would hurt municipalities, which get much of their income from the grocery tax. Then-Rep. Jim Simpson, Republican of Gulfport, warned that the grocery tax cut would seriously hurt coastal cities destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

"Is this the time for us to jerk out from under them the only source of revenue they have?" Simpson said in The Clarion-Ledger. "It would bankrupt Pass Christian and Long Beach."

The argument worked well enough for the governor to veto the tax bill without much public outcry in 2006.

That same year, Barbour succeeded in dismantling the Partnership for a Healthy Mississippi, a private, non-profit organization that received an annual $20 million from a multi-million-dollar tobacco settlement.

With its television advertising and anti-smoking education outreach in the state's schools, the program had shown huge success in cutting the state's number of minors consuming tobacco.

Barbour, however, said the program was supporting partisan efforts in helping the state's Legislative Black Caucus, which consisted mostly of Democrats.

Judge Jaye Bradley vacated her 2000 decision allotting the annual $20 million to the Partnership, arguing that her earlier decision meant nothing if the governor's office and the Legislature didn't agree on it anymore, effectively killing its funding.

The following year, tobacco-tax advocates were still pushing for a tobacco-tax increase, and trotted out a new plan, which would funnel surplus from the increase into an account to reimburse municipalities. The Municipal League of Cities accepted the plan, but Barbour still opposed it, and made sure that key senators killed the proposition before the popular bill got to his desk and forced him to veto it.

Former Sen. Tommy Robinson, of Moss Point, lost to his challenger in the 2007 Republican primary, partly with the help of anti-tobacco organizations that advertised Robertson's role in killing the hospital/grocery tax swap of 2007 while he was chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Barbour selected Robertson to serve on a state commission to study the state's tax system in January 2008. But after Moss Point police charged and jailed him with drunk driving in February, his third offense, Robertson resigned from the commission in March.

The fight for a tobacco tax continues. This year, a largely partisan group of House and Senate legislators pushed the tax as a means to close a Medicaid funding shortfall, resulting from a hospital tax earlier rejected by the federal government prior to Hurricane Katrina.

Barbour still opposes the effort, claiming he is waiting for a special commissionthe same one temporarily featuring Tommy Robertsonto finish its statewide assessment of the tax system. He said he wants no tax changes until the commission delivers its results and, instead, called upon hospitals to fill the gap.

Progressive Democrats, however, got mileage out of the argument that Barbour's hospital tax would be passed down to patients, and armed themselves with statewide polls showing the public's overwhelming support of the cigarette tax over the hospital tax plan.

The June poll, financed by the anti-smoking group Communities for a Clean Bill of Health and conducted by Republican pollsters Public Opinion Strategies of California, found that 80 percent of Mississippians polled preferred the tobacco tax, while only 8 percent wanted Barbour's hospital tax.

Playing Chicken

The governor was unable to sell his hospital-tax demand to the public and resorted to another tactic. In the midst of the summer 2008 special session, he threatened to cut Medicaid by $375 million, the resulting financial hole if the state does not plug the shortfall in the state's matching funds. Hospital advocates warned the cuts would force closings and massive layoffs in hospitals and nursing homes, heaping low public opinion upon the governor.

Rumors began circulating that Barbour was willing to contemplate a cigarette-tax increase during the next legislative session if House Democrats would endorse his hospital tax this year. Holland told WFMN Supertalk hosts at the recent Neshoba County fair last Thursday that the House will need more than contemplation for next year.

"He's had years to approve a cigarette tax, and it hasn't happened, yet," Holland said.

Now the governor's call for the $375 million cut faces even more opposition. He had planned the cuts to begin in July, but attorneys for hospitals took the state to court last month, demanding it provide more details on what impact the cuts would have.

Hinds County Chancery Court Judge William Singletary ruled that Barbour could not bypass the Legislature and raise hospital taxes, and Hinds County Chancery Court Judge Patricia Wise ruled last week that Medicaid had to provide more clarification on the impact.

Medicaid withdrew its plan to cut the program last week. Barbour veered away, at least temporarily, in the legislative game of chicken this year, but veered quickly behind the roadside billboard of compassion. Barbour said he was working with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and its Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which oversees Medicaid, to tweak the $375 million cut so as not to do as much damage.

"We're going to delay the cuts further ourselves because we've found a way that will do much less harm, and that's worth waiting an extra 25 days," Barbour told reporters last Thursday, adding that the cuts are still necessary, and still–of course–all the House's fault. "They'll have to be made unless the House passes a firm, sustainable plan to fully fund Medicaid, and they haven't done that," he said.

House members were furious. "Don't let him tell you he doesn't have a choice. He does have a choice," argued House Public Education Committee Chairman Cecil Brown, D-Jackson. "We've offered other solutions. We've offered a tobacco tax, which has widespread approval; we've offered to take it from the state's rainy day fund; we've offered a compromise on a hospital tax/tobacco tax combination.

"He's not interested in a compromise. It's his way, or nothing. This decision is on one person's head. You've got only one person in the state of Mississippi threatening to cut $375 million out of Medicaid, to hurt people across the state."

House Medicaid Committee Chairman Robert Johnson, D-Natchez, pointed out that Barbour has not made cuts during the last few years of Medicaid shortfalls.

"For the last five years, we've had a deficit, and the governor had not made a cut. The idea that he has to make these cuts because of a constitutional requirement when he hasn't made them before, there's no reason for him to do it now," Johnson said.

Johnson and others learned this week that Barbour was seemingly willing to twist state law into knots to avoid making cigarettes even slightly more expensive.

Barbour did not return calls for this story, but a statement on his Web site says: "The new solution means funds cut from reimbursement payments to hospitals will be replaced in like amount by distributions from a different Medicaid program, resulting in approximately $370 million being paid to hospitals to make up for cuts required by state law. The solution will protect the program by generating $88 million of the $90 million shortfall in the state Medicaid share through increasing the current gross revenue assessment on hospitals. The other $2 million will be generated through cuts of less than 1 percent on other provider services."

Barbour said in the statement that hospital and nursing-home provider fees are playing a significant role in the plan. "Hospital and nursing home provider fees account for about 30 percent of Mississippi Medicaid's funding. The plan I am announcing today uses the benefits of those fees to attract the maximum federal match to state Medicaid dollars," he said.

'A Differently Dressed Mule'

Barbour's plan, when detailed on Monday, left one senator's head spinning.

"He says he'll create a shortfall in the Upper Payment Limits ('UPL') program, which he then will use to justify imposing a gross assessment on hospitals in the amount of $370 Million," said Sen. David Baria, D-Bay St. Louis, who replaced Sen. Scottie Cuevas last year. (Cuevas regularly voted in line with Barbour.)

"Put another way, the governor takes money from hospitals and gives it back to them, and in doing so creates the illusion that there is a deficit in the UPL program."

Baria said that Barbour thinks the resulting deficit, "however illusory," empowers him to assess hospitals to make up the difference.

The governor maintains that his plan has received preliminary Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approval, but Baria said preliminary approval is not the same as approval.

Rep. Brown, an accountant, said he would never advise a personal household to finagle its budget in so complicated a manner.

"There are too big problems with this. It's still a $90 million tax on hospitals, no matter how it's twisted," Brown said.

"Why would you go through this much trouble when all you have to do is increase revenue with a popular tax?"

House Speaker Billy McCoy, D-Rienzi, agreed with Brown, describing the plan as little more than a sleight-of-hand movement concealing the same hospital tax that the House finds unpopular with voters.

"It's just a differently dressed mule," McCoy told the Jackson Free Press, explaining that voters preferred the cigarette tax over a new fee on their hospital stay: "It remains to be seen if this thing will get approval all up and down the line."

Brown added that a second problem with the plan is the potential impact it will have on hospitals. "It's going to hurt some hospitals pretty badly and nobody knows which ones or how much," he said.

Mississippi Hospitals Association Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Mike Bailey told House members during a Monday committee meeting that his organization had not received details on how the tax would hit hospitals. The MHA earlier backed Barbour's hospital bed tax during the regular session, but later put its support behind the House hybrid plan of a tobacco/hospital tax combination.

Barbour's new plan still has no place in it for a tobacco tax.

MHA Strategic Communication Vice President Shawn Lea said MHA's information had received no updates by Tuesday.

"We still haven't seen any particulars of (Barbour's) plan or seen on paper how it affects individual hospitals. We are waiting for more information from the governor's office and the Division of Medicaid," Lea said.

The MHA continues to interpret the plan as a cut to Medicaid and could continue to litigate the matter in court, arguing that Barbour can't make the cuts without legislative approval. Lea gave no indication that a suit was pending on Tuesday.

Still, the Barbour-led Senate was happy enough with Barbour's untried numbers to make a quick exit on Monday. Senators abandoned the ongoing special session dealing with the Medicaid issue after again blocking the House's attempt to consider the tobacco tax hike. The House's latest plan had reduced the tobacco tax to a 44-cent hike, although Lt. Gov. Phil Bryantwho spent his 2007 election swearing loyalty to Barbourdecreed his faith in the governor's plan and would not consider the House plan in the Senate.

The Senate abandoned the chamber fast enough to forsake a nearly complete bill establishing the Mississippi Public Health Laboratory as a new administrative unit of the state Department of Health and creating a state fund to cover the lab's costs.

The current lab faces a loss of CMS certification this month. Both the House and the Senate had passed identical bills re-establishing the lab, but Baria held the bill on a motion to reconsider in an effort to detain the Senate.

Senate leaders refused to be detained, however, and tossed the bill over their shoulders on the way out of town.

With nowhere to go, the House walked away from the special session Monday after the Senate locked its doors.

An Oasis of Easy Cigs

Even as Big Tobacco has a devoted guardian in the Mississippi governor's seat, other states in the South and beyond have regularly increased their excise tax on tobacco as the national economy plummeted over the last eight years.

The national average for cigarette taxes is $1.18 per pack, with about 20 states charging that much. Ohio has a $1.25 tax on a pack of cigarettes, generating a total of $955 million in 2007, according to the national Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Pennsylvania, with its $1.35 tax on a pack of cigarettes, generated about $1 billion that same year, as did the state of Michigan, with its $2 tax on cigarettesdespite falling revenue from smokers relinquishing their increasingly expensive habit.

Even tobacco-growing Kentucky has a 30-cent tax on cigarettes that generated $177 million in 2007. North Carolina, one of the largest tobacco producers in the nation, has a 35-cent tax that generated $235 million for that state that year. Virginia, yet another tobacco producer with a 30-cent tax, collected $171 million.

Mississippi's 18-cent tax hasn't changed since 1985, generating only $43 million in 2007.

Rep. Brown said the numbers would be different without Barbour's influence and accused the governor of usurping voter's preferences during the legislative process. "If Barbour had simply let the Republicans in the House vote the way they wanted to, we would have been out of there weeks ago," Brown said.

He added that some Republicans had admitted to him that the governor keeps a firm hand on how they vote on tobacco issues and dare not buck the powerful former RNC chairman's wishes.

"They've told me that Barbour has meetings with Republicans in the House, and he threatens them politically, tells them how they need to vote," Brown said.

Barbour did not return calls for response.

Those whose loyalties waver in favor of their voters have found themselves facing a Republican opponent in the primary packing the governor's endorsement.

Former Rep. Clint Rotenberry, R-Mendenhall, lost to a challenger in the 2007 primary that he said was fielded by Barbour. Rotenberry, who was treasurer of the Mississippi Legislative Conservative Coalition in 2003, said he had disagreed with Barbour on some education issues in 2005.

"That's the way things are. Personally, I wouldn't care to follow the will of anybody other than my constituents, but that's the reality right now," Brown said.

Comment on this story at jacksonfreepress.com or e-mail Adam Lynch at [e-mail unavailable].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID