Wednesday, February 28, 2007

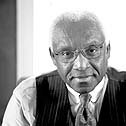

Ward 2 Councilman Leslie McLemore is rarely afraid to speak his mind. He started young when it comes to being vociferous. He began his career as a social activist fresh out of high school, traversing the state and helping to organize demonstrations and voter-rights campaigns in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He was vice chairman of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party's original delegation to the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City and remains an authority on the MFDP.

Though McLemore is qualified to speak on history merely on the basis of living it, he's got enough tenure to choke Freud, with a Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts, an M.A. from Atlanta University and a B.A. from Rust College. He's also been a post-doctoral fellow at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute for African American Research at Harvard University and has clocked in time at the Institute for Southern History at Johns Hopkins University.

At this point, the professor has gotten good at government scrutiny, and is often the first council member to voice concerns at a possible civil-liberties infringement or an illegal use of power of a government branch. More than once, McLemore has demanded clarifi cation from the Attorney General's office on the possible encroachment of the council's power by former Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr., and has sounded more than one alarm about the constitutional violations of now-Mayor Frank Melton.

So you say you're 66. I guess that your teen years were during the time of America's social awakening, right? Near the tail end of the civil rights era? How deeply imbedded was your family in the Civil Rights Movement?

Well, I graduated from high school in 1960. That was the beginning of the sit-in movement in 1960—actually in 1958 or 1959, they had the sit-ins in Oklahoma City, but I was in high school during the era of the Montgomery bus boycott involving Martin Luther King, so in my own mind, I was fairly concerned about issues and was spurred on by King's efforts early on. I lived 150 miles north of where Emmett Till was murdered. I became concerned about my surroundings and the world at an early age.

Where did you grow up?

It was a little place called Walls, in Desoto County. It was just incorporated for the first time about four years ago. It's a lot larger than it was when I grew up. It's about 25 miles north of Tunica, along Highway 61. This was a little farming town where two or three landowners owned all the area except for a few little plots. But I got involved in civil rights even before I graduated high school.

As a civil rights activist, did you travel all across the South, or just work in this region?

Well, I worked primarily in North Mississippi, but worked as far south as Jackson. It was only after I'd graduated from college that I really worked in other places when I became a staff member on the Freedom Democratic Party.

What was your job title on the staff?

I was a SNCC (Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee) student field secretary. I was on the staff of SNCC, getting paid by SNCC and working for the Freedom Democratic Party. Ella Baker was head of the Washington offi ce of the Freedom Democratic Party. I graduated from Rust College in 1964, and then went to work for the Freedom Democratic Party in Washington D.C., but even at Rust College, I was involved in voter registrations and other statewide activities centered around voter registration. Then in 1963, they had this statewide freedom vote campaign, and I was like the northern coordinator of the Freedom Vote campaign in Mississippi when Aaron Henry ran for governor and Rev. Ed King ran for lieutenant governor. In 1962, I was involved in the campaign of the first black people to run for U.S. Congress since Reconstruction.

How does a budding young "communist" invader like yourself keep food on the table while you're out flipping society upside down?

If you're a multi-tasker, you can do it, and I was a multi-tasker before the term was created. It was important for me to have a focus. Rust was a hotbed of civil-rights activity, and the students were already organizing before I walked onto the campus. There was boycotting in downtown Holly Springs, and they temporarily closed down the downtown theatre in Holly Springs. Small towns were organizing in voter registration, and there was an NAACP chapter on the campus of Rust College. That was the forerunner of

my involvement in SNCC.

Did your work cause tension for him?

He was a pillar of the community, and didn't anything happen to him or my mother. They were always concerned about me, but thank God, nothing ever happened to them.

I guess being a landowner gave him an advantage?

He sold real estate, built and bought houses. Walls is virtually on the Tennessee-Mississippi state line. Walls was 13 miles from the city of Memphis in my day, and now it's two miles from the city

limits. My grandfather owned land in Shelby County, and he sold insurance and ran a little café, open primarily on the weekends, in my hometown. My mother worked in an upholstery factory in Memphis, so they didn't depend on the local economy for their livelihood.

Was the Vietnam War ever a factor for you or your family, or your neighborhood?

I had graduated in 1964, and that's when I got an invitation from my draft board. I applied to both law school and graduate school as soon as I graduated from college.

My grandfather took me to the draft board in Hernando; he knew some people on the draft board. He went with me and exerted some influence. They told me as long as I was in school that they wouldn't bother me. The draft boards were localized, composed of leading white citizens in the county, depending on where you were, but in my case, we had so few people going to college and graduating from college that we were able to make a case for me.

Where'd you go to high school?

Hernando Central High School.

Might I assume it was segregated?

Oh, Adam, let me tell you. It was located in one building that had been a two-room school, but we also went to school in a series of three different churches in what was called the west end, which is the black section of Hernando.

The black school consisted of this one building and three different churches, and we exchanged classes by walking down the gravel road, going from this school to that school. They didn't build a regular school until the 1959 school year. In January 1959 we moved into a school with an indoor gym. Prior to that, we played all our basketball outside on the ground.

How'd the white counterpart look?

Oh, it was nice. On the eastern part of town, you see. It had been there for years. I remember the white kids riding the bus past us as we were walking to school.

There was no denying the disparity then?

We had the same superintendent for both black and white schools, and the resources clearly weren't put equally into both.

Sounds like I'm hearing your first few vestiges of social consciousness here.

Oh, it was before that. In fifth grade, sixth grade and seventh grade, I was head of my class, and in eighth grade I was class president. I got involved early on.

What was your first interest? Teaching?

It was medicine, actually.

What shifted you over?

The Civil Rights Movement, obviously. I decided during the voter-rights drives to become a lawyer.

What was it like in the Movement?

It was a world unto itself. I don't know if you've ever been involved in anyone's campaign, but it was my first feeling of a sense of community because you're surrounded by

people who are committed to the same thing you are. It's like an expansion of your family. Even though there's no blood ties, the philosophical ties are incredible.

You're thinking that you're going to change the world and the circumstances around you, and that's an exhilarating feeling. Sure, there was fear, but it was overcome by the fact that you knew you were making a difference. You were working with other people who are committed to the same principles. It's unlike any feeling that I've had since.

How did you end up at Jackson State?

How did you end up at Jackson State?

I always wanted to come back to Mississippi and run for public office. When I contacted local institutions for teaching positions, JSU made the best offer, and quite frankly, the first offer. I'd looked at JSU, Rust College and Tougaloo. Heck, I'd even applied to the University of Mississippi, but they were not about to hire a black person in 1971, and I was spending that year as a post-doctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore, after getting a

PhD at the University of Massachusetts.

As late as 1971? I guess the Civil Rights Movement didn't get everywhere then, eh?

Yeah, but you have to admit it was light years from where we had been. The state and country had moved from the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, and the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, so we are looking at such profound changes in law, and all that within six years. We'd made a tremendous shift. When I came back to Jackson in 1971, it was not the same place I'd worked in 1964 and 1965. The whole atmosphere was different.

What's the most memorable moment you recall out of the civil rights era?

One of the ones that made an impression was the first time I met Fannie Lou Hamer. I met her on a bus going from Cleveland, Miss., to Georgia, going to a voter-registration training workshop. And with us was Andrew Young, and Gene Young, his late wife, Dorothy Cotton, and Hosea Williams, who were teaching in that workshop, along with a woman by the name of Septima Clark, who was the head teacher. We were going from Amzie Moore's house in Cleveland.

What was Hamer like?

She was dynamic. This was early 1963, and she had been expelled from the plantation the year before and had become active in SNCC. A busload of us—along with Diane Nash and James Bevel; Miss Hamer sang gospel songs and freedom songs—participated in the role-playing and simulations in the workshop. I was really impressed with her, and it was a moment in my life that I'll never forget. I also got a chance to meet Medgar Evers and Bob Moses (SNCC project director and founder of The Algebra Project) in the latter part of 1962.

Tell me about the Fannie Lou Hamer Summer program.

We started the Fannie Lou Hamer Institute on Citizenship and Democracy in 1997. Four or five of us were in this workshop in the Civil Rights Movement at Harvard, and it was a five-week institute at Harvard. I had been one of the few people in the institute who had been an active participant in the Civil Rights Movement. I was in this workshop with a guy named Chuck McDew, who was the first chairman of SNCC, and Julian Bond was there. The five of us were assigned to do a group project, but while a lot of other groups were doing bibliographies and a reading list on the Civil Rights Movement, we decided we would instead form the Hamer Institute, which replicates the civil rights workshops and involves schoolteachers and educators. In 1998 we held our first workshop for teachers and high school students here in Jackson, over at JSU. We use it to explore the issues of citizenship and democracy. We look at the civil-rights narrative over the long term, starting with Africa and coming up into the

contemporary time. We look at this 400-year period and this centrality of struggle and this quest for freedom. We look at it from the bottom up, not the top down, through the eyes of the people who lived it.

What special guests will you have this year?

We've invited Bob Moses, who's come to several of our workshops. We've invited (Movement veteran) Dave Dennis, who has worked with Bob Moses as co-director of the Algebra Project, and Charles McLaurin, the young man who got Fannie Lou Hamer

involved in the Civil Rights Movement. When she was expelled from her plantation in Sunflower County, Charles retrieved her from Tallahatchie County where she'd gone into hiding and brought her into SNCC.

You know, I spent some of my childhood in a town where I'm pretty sure she got beat up in a local jail there. Ever heard of Winona?

Of course.

Is it true they abused her there?

You must know that Ms. Hamer was born in Montgomery County, Miss., and Winona is the county seat. The irony is that she was beaten severely in the county she was born in. Miss Hamer was beaten there, and several other people were beaten there as well. Euvester Simpson Morris, who lives in Jackson, was on that (fateful) trip with her when they stopped at the bus station there in Winona.

I never knew about the little secret there until adulthood. Is that a problem with kids all over the Mississippi—that they don't know the history surrounding them on every side?

That's one of the reasons we formed the Fannie Lou Hamer Institute, so we can help inform citizens about Mississippi's history, and that's why this proposed civil rights museum and the proposed civil rights trail are so important, so people can learn the story of our state's role in the civil rights era. It was not captured in your textbooks in Montgomery County, but that's gradually changing.

Your spot at the city council is not the first political seat you've ever run for. What other seats have you chased after?

I ran for the U.S. Congress in 1980, in this congressional district. Jon Hinson was the

Republican incumbent. I ran as an independent, and I came in second in a four-person race. The nominee was a guy named Britt Singletary, and he came in third, I came in second and there was another white guy, an independent, who lived over there in Clinton.

How did independents get so much strength in the race?

How did independents get so much strength in the race?

Primarily because the black Democrats were concerned about William Winters' elimination of the co-chairmanship of the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party had had a black and a white co-chair, but in 1980 Winter eliminated the co-chairmanship and just appointed a white chief, so there was some displeasure in the ranks of the black Democrats, and we forged this independent posture. This was our way of sending a message to the Democratic Party that black people shouldn't

be taken for granted.

Today, William Winter doesn't seem like the type to try to set black people back.

Well, he has clearly evolved from his days of being a segregationist to where he is today. We've witnessed the evolution of so many white southern politicians. The Voting Rights Act had an impact on many politicians in the South. Blacks began to vote, and people took on different attitudes.

Can you name any who changed?

Well, most any politician who was active in the 1950s and 1960s made the change. The biggest one would be George Wallace. Heck, he's the poster child. … He publicly apologized for the things he'd done and said. It wasn't uncommon, but a lot of them said they were products of their time and that if they'd spoken out they would have never won an election to office. Clearly, the black vote had something to do with that attitude change.

What was it like being black and running for a political spot in Mississippi then?

It was a major effort at organizing the congressional district. Charles Evers had run for Congress in that district, but nobody had put together a campaign like we were able to pull together in the 4th Congressional District because we tried to organize county by county. We set up McLemore support committees in all of the counties in the district. I think the organization that we set up gave both Rep. Robert Clark and Mike Espy some ideas on how to organize a campaign from the black side.

What were the demographics of Jackson at the time?

They were changing. Even in the early 1980s, you noticed some decline in the African-American commercial districts (like Farish Street and Lynch Street) after desegregation. The physical appearance of the city began to change as people had other business opportunities and other housing opportunities, because a lot of the subdivisions that had previously been all white. Black people began to move out of the inner city and into some of these surrounding subdivisions, and eventually to the new suburban communities.

Watching the black population chase the white population further out in to the suburbs, do you ever wonder that we ultimately failed in desegregation?

Oh, yeah, yeah. Absolutely.

What should we have done to get it right?

We should have built more safeguards. We should have paid just as much attention to the economic aspect as to the political aspect of it. We should've had more concern about ways to build up economic independence in the African American community. We should've been much more vigilant in encouraging the development of the black business class, and we didn't do that. Black people didn't get a piece of the pie while we were developing the political mechanisms of desegregation. The assumption was that once we got the political power, the economic power would either come with it, or it would come along right behind it.

Many still won't hire blacks. I see small business in Jackson and in the suburbs with no blacks anywhere in management.

There is this historic pattern that's been built up over centuries. They're accustomed to black people buying from them, working for them, voting for them. It's a pattern of the last 400 years, and it's going to take a long time to change it.

How do you change it if only one race is really interested in pursuing the change?

You live and work and try to make sure you have substantial laws in place, and you create an atmosphere where both whites and blacks can function together. The key here is the education system. The problem here is that we've got two very distinct K-12 systems. We live in segregated communities, more or less, and we go to segregated schools, more or less, so that we don't have any coming together until one goes off to some college or you go off into the working environment. But you can't force this on people. You need a process where people just want to go to school together and see more than just race.

What was it like under Mayor Johnson? I understand there was the occasional tug of war between the legislative branch and the executive.

It wasn't just Johnson. It's the nature of the system of government that we happen to be a part of. There's this creative tension that's between these two systems of government, and I think the tension is good. If you didn't have that or the separation of power, you'd have a king or dictatorship. Black folk and their white allies have fought too hard for us to resort to a dictatorship.

Some of our JFP bloggers seem to think that one side of city government is winning these days. Got anything to say to that?

We really have a strong mayor/weak council form of government, and the mayor is charged with the responsibility of executing and directing the government. Given that you have a person who is responsible for executing the law, responsible for the city departments and divisions and for implementing a policy, that gives them an advantage.

Speaking of departments, what's the latest on interim department heads?

Speaking of departments, what's the latest on interim department heads?

The mayor has held up the process, and in one sense, we have given him free rein in that we haven't been consistent in insisting he bring his picks forward. He's been able to backtrack on the issue, and because it's seven of us with seven different points of view, it's hard to stay on point with the issue, especially with so many other issues hitting us on a weekly and a daily basis.

Is a majority on the council happy having interim directors?

The council functions on the majority, and it takes four votes to constitute a majority. Mayor Melton has been very good at maintaining a four-person majority.

Has the council president joined you, at least temporarily, on forcing a vote on the interim directors?

Ben Allen is the swing vote, but the mayor seems to have the automatic vote on so many occasions. I think (Allen's) been onboard regarding the interim heads from the beginning, but you have to follow through on these issues. But the interest wanes from week to week and month to month.

Can the council force a vote?

We are going to forward that decision. We're going to work toward asking the mayor to bring forth people in a reasonable period of time. These (positions) should've been filled on a permanent basis a long time ago. We really need to get the message across to the mayor that we're serious about the confirmation process. But I must say, in spite of the nature of the council and who's in the mayor's office, I have noticed a city that functions very well. We have generations of city workers who have kept this city going in spite of the politics going on around them.

It seems like there are four people on the council in accord regarding the employment agreement of Sarah O'Reilly-Evans' contract. What's happening with that?

We, as a council, signed off on her contract. Now some of us don't remember some sections of it, like the section allowing her to get extra compensation for working on bond projects, because we didn't have a discussion of that. O'Reilly-Evans makes the case that it was a part of the original contract, but some of us have our doubts. Nevertheless, with all of that said and done, we approved the contract. I am really not sure about what we can do about that now. We've been discussing this behind closed doors, but I'm not sure we have any power to revoke her contract. There are a variety of opinions from a variety of different lawyers. The case has been made that once we agreed to her four-year contract, which was unprecedented, that we should've had a legal adviser from the legal department advising us about the contract. That did not occur, and so we have these contradictory decisions. But I think as long as Melton is in office as the mayor, my thinking is that she's probably going to be able to maintain her position and retain her contract.

Four members of the council appeared ready to cut city legal's pay if it doesn't represent both branches.

I think the four of us, on this particular issue, are still committed, but the complicated part is: What is the legal strategy now, that we will all buy into, that would force some kind of conclusion on the biased representation that we get? Are we willing to withhold funds to the legal department? Are we willing to withhold funds on the claims docket? Are we willing to send that kind of message? Are we willing to systematically decide which areas we're going to de-fund?

We haven't agreed on the approach. We're displeased with the quality of the legal representation, and we think it's a fatal flaw in the state statute taking away the council's right to maintain its own legal representation.

So the council isn't quite as willing to cut the legal department as it to be appeared two weeks ago, right?

No, we have not agreed on the next … legal steps.

What's the issue with city legal being dominated by the executive?

Statute says the legal department must provide legal advice to the city of Jackson: that's the mayor and the council. A lot of people don't understand that, and the council members who are pro-Frank Melton work very hard to cloud the issue so people will not understand it. When we say city legal is to provide representation for both branches of government, they jump on the argument that the mayor is supposed to direct all departments—which is true, except for the case of the legal department. That's why I think the only way we're going to get this changed is to go to the Legislature and change state laws.

I think we'll make a good case to the Legislature, but we'll still have to wait for the next session. Still, there's nothing to keep the council from spending the rest of this year making its case. We can't let up on this issue. We've been arguing about this since I got on the council in 1999.

Let's talk about your interaction with the mayor. When did the first warning light go off?

(Drops to a hushed tone) In July, when the mayor was first sworn in. That first week. That first council meeting, when the mayor pulled off this sort of coup with (Ward 6) Councilman (Marshand) Crisler. The red light went on for me then because Harvey Johnson, as mayor, had not been that overtly involved in trying to manipulate the direction of the council. That said to me then that we're in for a different ride.

Were you surprised that some council members were so easily influenced?

I'm not surprised at how easily the new members were manipulated. The actions taken by Ward 3 Councilman Kenneth Stokes and Mr. Crisler initially surprised me. On the other hand, one has to give kudos to the mayor for being able to pull those people together with whatever bait he used. Obviously, I was caught off guard. I think other council members were caught off guard.

When you're referring to the mayor's dabbling with the council last July, are you talking about the weird partnership bonded between Crisler, Stokes, Bluntson and Tillman on picking Crisler as the new president over you?

Oh, yes. I'm talking of the coalition between them.

Do you want to speak more on that?

No, that's water under the bridge, but it set the tone for the administration.

Have these kinds of voting blocs been an issue in the past?

Well, you've been around city government for a while now. It's not uncommon for all city administrations, either in Memphis or in Jackson, for the mayor to pull together a coalition of supporters. It's happened during the Ditto, Danks and Davis administrations.

You seem to be making a habit of calling out the mayor whenever he does something unconstitutional. Is it wearing on you, yet?

I was elected to represent the citizens in Ward 2. I've always tried to interpret the statutes as best I can and to try to bring attention to issues that I think are not within the grounds of the statute, and it's not wearing on me at all. I was elected to do this, and I'll do it as long as I'm re-elected.

Yeah, but there are letters in the paper every day. You know the ones: "Why don't ya'll just leave the mayor alone and let him do his job?" or "… at least he's doing something." Are you afraid you're losing voters who may be Melton supporters?

Hopefully, if I lose some voters I gain supporters. Ward 2 has never voted for me 100 percent. There have always been people who have voted against me, but I'm hopeful that some of them will vote for me. I've always followed my obligation to represent Ward 2 and uphold the state statute. When the majority of the citizens in Ward 2 say I'm not doing what they want, then I'll have to abide by their decision at election time.

I have a ward with a number of highly educated people who take an interest in city, state and national politics. My predecessor, Louis Armstrong, knew this. On any given day, there are a ton of people in my ward who think they can do a better job.

Give your opinion of the mayor's abilities.

Give your opinion of the mayor's abilities.

I don't think he has the posture; I don't think he has the composure—I don't think he has a real interest in government. I think he wants to help the citizens and do the right things, but I don't think he has the demeanor or the personality for government. He says himself that he doesn't have the patience to do the day-to-day things to run a city like ours. I don't think that's his strength.

Yeah, but is he working? Can we say that he's brought any great things to the city?

Well, he started off surrounding himself with good people, and he inherited good people, but from my perspective, I don't think he's the best judge of talent. If you are impatient and don't have the temperament to govern, you should at least keep surrounding yourself with good people who can govern and then you can go off and play cops and robbers as much as you want. You need good decision makers and you have to let them work, but he has not done a good job of that.

From a political science perspective, how will Melton's term will be remembered?

As a term of great controversy. As the first mayor, in recent memory, who had to stand trial, who was convicted on misdemeanor charges and who had charges brought against him as a felon while in office. The trial hasn't played out, yet, but this is unprecedented.

What about the projects coming into the city? The mayor spoke of at least $6 billion worth of projects on the way.

The proof is in the eating of the pudding, and that has yet to come. Now obviously a lot of these projects you're talking about, the $6 billion, were on the table before Mr. Melton became mayor.

Let's talk about the chief. Have you gotten a crime plan from her, yet?

No, I haven't, except that the chief has the right idea in mind on focusing—as the previous chief did—on community policing as the way to make the police department an integral part of the community. However, the chief really has not brought forth a comprehensive plan to keep replenishing the police force. There has been too much talk and not enough action in terms of presenting, in a concrete way, plans to the city council from the executive branch and from the chief. We need a plan on how we retain people, how we recruit people consistently, how we can be consistent in applying our policy and persistent in providing community policing throughout the city. We have a case now where the police chief is clearly overshadowed by the mayor, who is acting as police chief.

What about those police pay raises the chief spoke of?

She spoke of them, true, but we're looking for a plan coming from the executive branch and the police chief on how to pay for them. We need for them to be on one accord when they bring something to the city council, so that we can act upon it. Remember Anderson's proposal on funding the pay raises? Remember how the mayor disputed it soon after? We don't need the chief singing one song, and the mayor singing another one.

Is the council still pressuring the chief to produce ComStat figures?

Yes, but I don't think the chief is forthcoming on it. If we had a full council pressuring her she might be forthcoming, but some members of the council aren't behind the push. The chief only sees Barrett-Simon, McLemore and Crisler, but we don't constitute a majority of the council, so the chief can say, "Well, I'll release some occasional figures, but occasionally I won't."

What do you think is the motivation behind the administration's push to retire ComStat?

The chief doesn't want to share the bad news, of course. She wants to put the best face on the work of the police department.

Anderson said that ComStat production is under-funded. Has the funding changed since the administration changed?

The funding hasn't changed as far as I'm aware of, and if it has changed, then this information has not been brought to us.

Final question, I promise: Who named you Leslie?

My mother named me after my grandfather. Her father was Leslie Williams, and my father is Burl McLemore, who is 88 years old and lives in Memphis.

For a history of Mayor Melton's controversies, see the JFP's MeltonBlog

Previous Comments

- ID

- 80924

- Comment

Adam this is an excellent interview. I was right out there when McLemore came aboard. He really was a tireless worker and very inspiring leader to be so young. I have watched him grow into a fine man and good leader. If the rest of the council was as caring and knowledgable about goverment we would be much more advanced. I hope he continues to keep his head above the frey and continue to try to get the council to wake up and govern according to the all laws. I bet he is having a fit concerning the latest stunt the mayor has pulled. Just think the mayor might become a jailbird. It would be funny if it wasn't so sad.

- Author

- jada

- Date

- 2007-03-01T23:59:18-06:00

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID