Wednesday, November 14, 2018

JACKSON — For the past several weeks, students in my Social Stratification course read and discussed "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," the international bestseller from French economist Thomas Piketty. Published in 2014, the book's analysis spans more than 750 pages, and aims to show that in spite of—or perhaps due to—massive demographic and economic transformations over three centuries, economic inequality is increasing.

Piketty's analysis reveals the myth of meritocracy—people gaining power based on their ability—and challenges conventional wisdom on economic inequality and its root causes.

For example, many people believe economic inequality is rooted in a lack of training and skills. Here in Mississippi, those running for state-wide offices often structure their campaigns around conventional wisdom that says the pathway to economic mobility is through better workforce training. If only schools and colleges provided "real-world skills," they claim, then more Mississippians would have access to better-paying jobs and a better quality of life.

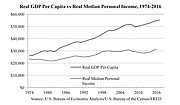

While many accept this as common knowledge, the data on economic inequality tell us a different and much more complex story. Consider the first chart, which compares Mississippi's gross domestic product, or GDP, per capita with the state's median personal income over the past 40 years. GDP per capita reflects the average value of goods and services produced, per person, in Mississippi.

Since 1974, Mississippi's workforce productivity has more than doubled, from roughly $26,500 per capita in 1974 to more than $55,000 per capita in 2017, adjusted for inflation. Yet workers' incomes have not kept pace. In 1974 the median personal income in Mississippi was just under $23,500. In 2016, it was barely $31,000.

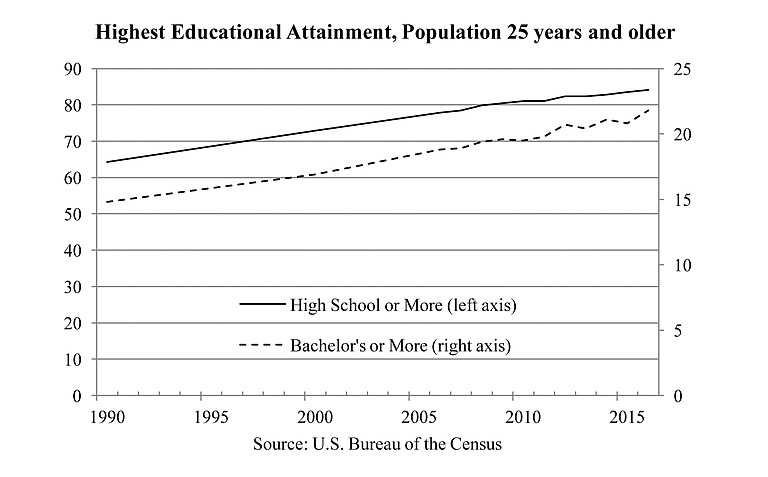

In addition to the significant increase in productivity, we also find a significant increase in the educational attainment of Mississippi's workforce population, shown in the second chart.

From 1990 to 2016, the percentage of Mississippians ages 25 years and older with at least a high school diploma increased from just over 64 percent to more than 84 percent. During that same time period, the percentage of those ages 25 years and older with at least a bachelor's degree increased from less than 15 percent to nearly 22 percent.

On their own, these two charts show that Mississippians are more educated than ever, and creating more value than ever. Yet their paychecks do not reflect this. If Mississippi's workers are producing more value than ever, yet receiving very little in return, where is all that value going? In the last chart, I draw from the World Inequality Database (find it at wid.world/world/) to help shed some light.

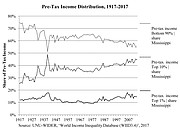

The chart shows the distribution of income to the bottom 90 percent, the top 10 percent, and the top 1 percent of all earners. In 1917, the bottom 90 percent of earners in Mississippi received three-quarters of all income, compared to one-quarter for the top 10 percent. The top 1 percent received 12 percent of all income, or roughly twelve times the average wage.

Yet by 2014, the top 10 percent's share increased from 25 to 45 percent, and the top 1 percent's share increased from 12 to 15 percent, or roughly 15 times the average wage. Meanwhile, the share going to the bottom 90 percent—the working class—fell to just 45 percent of total income.

If we put these three charts in conversation with one another, an important conclusion emerges: At the same time that Mississippi's workforce became more educated and more productive than ever, income inequality accelerated.

Improving our K-12 system and increasing people's opportunities for a college education are important goals that many of us share. Yet we should not fool ourselves into thinking that education is the pathway to economic equality. To meaningfully address economic inequality in Mississippi and elsewhere will require a complete restructuring of how income and wealth are distributed.

This restructuring begins by putting control of the economy in the hands of workers, and out of the hands of the elite and the powerful.

James M. Thomas is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Mississippi. Follow JT on Twitter at @Insurgent_Prof.

This essay does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Jackson Free Press.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID