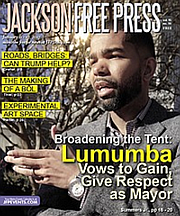

A younger Antar Lumumba was his father’s confidante and co-conspirator on how to solve Jackson’s problems. File Photo

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

JACKSON — Primary night wasn't supposed to end that way. Chokwe Antar Lumumba could not possibly beat nine Democratic opponents outright and avoid a run-off. A 34-year-old couldn't possibly cause a string of depressed watch parties around the city, save for his jubilant gathering at the King Edward Hotel and a party at a south Jackson church that felt like a family reunion for a political newcomer who could not have expected to win.

A Millsaps College-Chism Strategies poll right before the election had Lumumba at 29 percent, John Horhn at 20, Robert Graham at 19, Mayor Tony Yarber way back at 7 percent and the newcomer, Ronnie Crudup Jr., with even less. But the poll "did not accurately project the magnitude of the Lumumba victory and anticipated a run-off," Millsaps said in an understatement released May 4. In the primary, the winner nearly doubled that prediction with major inroads into traditionally white precincts.

Conventional wisdom dictated that more mature, reasonable voters would jump from Horhn to Graham or vice versa to help put an older candidate in City Hall, and keep out the graduate of Tuskegee University and Thurgood Marshall School of Law and his "scary radicalism," as one Horhn supporter and long-time political caviler called it in a vicious Facebook post the Sunday before the primary.

Broadening the Tent: Lumumba Vows to Gain, Give Respect as Mayor

The 2017 JFP Interview with mayoral candidate Chokwe Antar Lumumba

That comment hinted at the nastiness ahead if Lumumba were to duke it out with an older No. 2. Four years earlier, when Chokwe Lumumba Sr. also defeated the polling and incumbent Harvey Johnson Jr., his run-off opponent ran ads implying he was a black Muslim, and not a Christian, an inaccurate rumor that surfaced about the son this season.

But Jackson has been through hell since Lumumba's father rattled fearful whites when he ran for mayor, then immediately drawing multiracial admiration even from white conservatives because he was respectful and willing to compromise. The city then lost him way too soon; elected Yarber with multiracial support; endured nakedly greedy contract wars, budget battles and lascivious lawsuits; navigated metastasizing potholes as the mayor told us to pray them away; rolled our eyes at napkin subtweets; lost legislative coups over the airport and 1-percent sales-tax control; maybe got snookered by Siemens over water billing; and watched the state help elect a president determined to pull our federal funding if we don't help round up immigrants.

Water, meet the bridge. Change is in the air, and the people ended up knowing exactly who they wanted as mayor, or didn't want, sending Lumumba into the perfunctory general election on June 6 with 55.11 percent of the Democratic primary vote. He leapt ahead early on primary night and barely swerved to under 50 percent.

Put simply, he slayed.

The political class was right, though, that voters had soured on Mayor Tony Yarber and would turn him out with single-digit support (5.39 percent).

"Unless Yarber has a lot of money that we haven't seen, yet," one political watcher had emailed me in late April, "I don't think he breaks double digits. He was the NE Jxn candidate three years ago, and the buyer's remorse is almost as bad as with (former Mayor Frank) Melton."

Still, not even all of northeast Jackson, or white voters, broke exactly as many thought, with a lot of them helping the so-called "scary radical" pull off a landslide.

The reasons for that are varied.

Fear of a Lumumba

"Victory is mine. Victory is mine."

Like any Mississippi freedom fighter worth his salt, Lumumba sang a hymn first when he walked into a packed room at the King Edward Hotel just after 10 p.m. on primary night to greet his ecstatic believers. "Victory today is mine," he sang into the microphone, repeating lyrics gospel singer Dorothy Norwood made famous.

"I say that because it is not about me. I say that because you defied conventional wisdom today," Lumumba then told his people. He chided those who believed he could not win that day, even as he had been telling his well-cultivated social-media base that he would win it all that night.

"Conventional wisdom said that Jackson could not come together, but we saw today in this election, we saw northeast Jackson agree with south Jackson, (and) southwest Jackson agree with northwest Jackson," Lumumba said.

Neither Lumumba father nor son has ever shied away from the view that an economic system that so clearly prefers whiter parts of the city over the majority-black wards is broken and needs an overhaul. That call for equity is still radical, though, in a nation that recently elected a president bent on installing policies to benefit the wealthy and a state where the Legislature is giving salary supplements to teachers in wealthier districts and cutting funding to poorer, blacker districts.

Lumumba drew support from national progressives like Bernie Sanders and Howard Dean's Democracy for America for a reason. "We have two options," Lumumba said to a rousing call-and-response. "We have the option of economics by the people and for the people, or economics by a few people for themselves. And so we're making the decision that we're going to have a solidarity economy that works for all of Jackson," he promised.

Part of that economic vision is providing more work, pay and motivation to city workers rather than contracting the tasks, and profits, out to others. "We have to look at innovative ways of bringing in more revenue," he told the Jackson Free Press in January. "I have been talking about (the need to upgrade parking meters since) before the council started talking about them. ... I disagree with the theory that we outsource to another company to do this.

"I think that we can handle this ourselves, and the money that a company would take as revenue or as profit, we put back into our budget. Why aren't we doing this. Why are we looking to outsource every single thing?"

Then, Lumumba answered his own question. "Oftentimes when we outsource all of this work, that's paying back political debts. That's paying somebody a contract or giving somebody a contract that is going to put money back in your pocket. ... We don't have that luxury. Jackson is hurting, and the people need to see more for their dollar. And so we need to recover more money for the city."

'Build and Fight'

The win tickled national leftists no end. That night, Twitter stuttered with disbelief, much as it had the night Mississippians defeated the anti-abortion Personhood Amendment in 2011. How could such a progressive win in the heart of Dixie?

Lumumba, though, seems to smoothly navigate between national liberal dogma and local southern governing that seeks to bring more prosperity to everyday people. And between those who call for his father's long-time "Kush plan" that scares the dickens out of many white voters and the son's modern Jackson plan that he lays out on his campaign website starting with crime and economic development.

His "solidarity economy," should it come to pass, clearly will not pander to the typical power players, regardless of race, and it could mean less privatization and outsourcing, and a growth in city jobs. Lumumba wants 60 percent of city contracts, including subs, to go to people of color, and not just to help enable white applicants to haul in lucrative city contracts.

Like his father, Lumumba plans to put Jacksonians to work, support workforce development, and incubate and empower local businesses. He plans to use what he calls "leverage" to both get more businesses to set up shop in Jackson and to keep forces from outside from exerting too much control over the capital city that many of them, or their parents and grandparents, fled years ago after the U.S. Supreme Court forced local schools to finally integrate nearly 20 years after Brown v. Board of Education ended segregation, at least officially.

Lumumba is not pleased with deals that give up Jackson's farm to state power brokers, including many who do not live in the city. "We are going to make certain that we see the 1-percent-sales-tax plan that (my father) adopted go into fruition, go fully through, and that is not happening now," Lumumba said in January. "... What we designed to do with the 1-percent (sales tax) was to take the money that was coming in from that and leverage those dollars to take advantage that Jackson at that time had a really good bond rating."

A Chokwe Lumumba Sr. Primer

Who was late Mayor Chokwe Lumumba Sr.? Hear him in his voice, read interviews, see campaign donors here.

The presumptive mayor regularly talks about the need for a more positive city climate for entrepreneurs, promising to do what many candidates have pledged and then forgotten: simplify and automate licensing and permitting processes.

He wants to see more successful startups throughout the city, not just in downtown and northeast Jackson. On his website, he pledges to "generate an incubator fund to aid in the creation of new businesses in areas ripe for growth and renewal (i.e. Farish Street, Medgar Evers Blvd., Hwy. 18, Hwy. 18, Lake Hico, etc.).

"[W]e can't let ourselves just be focused on downtown," he told the Free Press in January. "We have to be focused around town. Because what you achieve if you don't focus around town is you see an island of wealth surrounded by a sea of poverty."

Still, Lumumba wants to see retail growth jump-started downtown, which has seen an increase in residential living and large projects such as the King Edward, the Standard Life and the Westin Hotel, but smaller businesses struggle to open and then survive. "We are (walking) on Capitol Street right now," he said during a January interview. "There should be opportunities to take people's money right here, in terms of businesses. There should be some opportunity where we have some retail spaces."

Lumumba wants it known that wide investment in Jackson is expected. "I am going to be a building mayor," he promised. "I am not going to stop development. At the same time, the tone that I want to strike is that we want businesses to come. We will do whatever we need to do to incentivize businesses coming. Come to Jackson and make a lot of money, but also invest the money back in the city."

One way to do that is through support of cooperative businesses, such as the Rainbow Natural Grocery Co-op in Jackson, which has long been member-owned. Father Lumumba had planned to help create a network of cooperatives here to help build a more bottom-up economy, and after his death, his son helped launch Cooperation Jackson to continue that vision.

The idea may scare old-school capitalists, but cooperatives are common in the United States, from tiny ones in granola towns to big names like Ocean Spray (juice), REI (sporting goods) and Land o' Lakes (butter), to rural telephone and electricity cooperatives. In some ways, they are free enterprise at its free-est.

This concept has strong support in the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, which his father co-founded, whose members can use stronger language than the son when talking about such goals, whether at a Harlem fundraiser for his campaign—an opponent mailed flyers for it around town in unmarked envelopes—or to progressive national publications.

"Cooperation Jackson is in the midst of a pivot that we're calling 'Build and Fight,'" Cooperation Jackson co-director Kali Akuno told the leftist magazine In These Times in January. "... This has to be a primary focus, and we want to build something that leans in an anti-capitalist orientation, like community-production based, cooperatively-owned digital fabrication."

Akuno served as director of special projects and external funding in the first Lumumba administration, focusing on cooperative development, sustainable practices and the promotion of human rights.

2017 JFP Endorsement of Chokwe Lumumba

Read the reasons for the JFP's endorsement of Chokwe Antar Lumumba for mayor in 2017.

Campaign rumors had it that Lumumba would pack the city administration with "Michigan" or "Detroit" people—the kind of entourage that can easily scare white voters. Outspoken activists such as Akuno are among those "outsiders" that detractors fear can push the new mayor to pursue radical agendas more than he will fix potholes and automate business licenses.

The presumptive mayor, though, told the JFP just before the election that he is not going to do that—and that movement supporters are not always the best city employees. This Lumumba said he plans to hire a diversity of qualified people and manage them well in order to improve city services and efficiency, even if that doesn't make everyone he knows happy.

Still, a central focus is his father's "People's Assembly" approach: "[W]e will adopt the same ideology that the people have to be incorporated into this process to a greater extent," he said in January.

That ideology has modernized, softened and morphed over the years as the city became more integrated and less violent toward black people, but it is still rooted in the same ideals—black people must be fully at the table, making decisions, reaping benefits and growing prosperity, not pushed to the side and controlled by white interests.

That is, the Lumumbas are still fighting for black people without apology.

'Free the Land'

The first time I laid eyes on Chokwe Lumumba Sr.—born Edwin Finley Taliaferro in Detroit in 1947—I was kicked out of the event because I was a white reporter. In late 2002, my newspaper was brand new when we got a press alert about a rally for Lumumba, whom a white judge was trying to get disbarred. My Czech photographer and I went to report on the man who had renamed himself after the Chokwes in Central Africa, who had defied slavery.

My First Encounter With Chokwe Lumumba

Soon after the JFP launched, Editor Donna Ladd tried to cover a rally for Chokwe Lumumba—where white media were not welcome.

After explosive talk from the podium, Lumumba's handlers said the media had to leave so they could strategize, but only asked the two white journalists to go, not those from black publications.

Then, I knew nothing about the Republic of New Afrika, the group of radical intellectuals he had accompanied to Jackson from Michigan in early 1971, determined to stop the carnage and keep more black people alive and safe, preferably living on their own land where radical racists couldn't control or hurt them. "Free the land!" was a rallying cry that also meant free the people.

I was annoyed at being asked to leave, but I was fully aware that the mainstream media in the city had never covered black freedom movements fairly—that the reports had to pass through a white lens to please readers and advertisers. Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. hadn't yet told me that media like The Clarion-Ledger were still "institutionally racist" in their coverage choices and tone, but it was obvious enough.

Besides, I had recently finished studying black freedom movements under Dr. Manning Marable—who would later win a Pulitzer for his Malcolm X biography—and I wasn't in a headspace to be easily offended by distrust of typical corporate media.

So I researched Lumumba's disbarment case, finding that he probably was being targeted for standing up against injustice, even if he was a bit disrespectful to the judge in the process. I reported on him fairly and respectfully, revealing both that they kicked us out, as well as the reasons he shouldn't (and wouldn't be) disbarred.

What happened next has defined this paper's interactions with the Lumumba family from that day forward—after my piece, his people called and invited us back to the next meeting. That time, Lumumba still boomed his disdain for the "white media," but made a point of turning to us and telling us that there are exceptions.

That is, the Lumumbas do not hate white people, even though they are sick and tired of injustice toward black people. Even after we declined to endorse Lumumba for mayor in 2013, he was respectful and accessible for repeated interviews until his untimely death. He never required complete agreement for civil discourse.

I later reported more on the RNA tragedy that still defines the Lumumbas for some people. One day in 2005, I heard that Imari Obadele was speaking at City Hall. He had killed a cop, a white leader told me with outrage while delivering a pile of police files on the shooting to me. That crazy attorney Chokwe Lumumba was part of the RNA terrorist group, too, he told me.

But the police files revealed a complicated tale of black activists renting two houses near Jackson State University months after the May 1970 JSU protest when dozens of police officers fired on unarmed students, killing Philip Gibbs, 21, and James Earl Green, 17. The RNA wanted to create a separate "state" for black Mississippians and bought land in Hinds County where it would start their safe space.

It was radical, but it was 1971, Jackson cops were killing unarmed black kids, and many whites still yelled at black people to go "back to Africa." Instead, this group opted to create a "New Afrika" inside a state where white people were fleeing Jackson and public schools in order to keep their children (and tax dollars) separate from black kids.

RNA members had set up their own Ruby Ridge-ish compound—two houses on Lewis Street—armed against attack, much as many white Americans still do today. News reports show that Obadele and JPD Lt. William Louis Skinner, the father of today's Hinds County Youth Court Judge Bill Skinner, had been at each other's throats across a divide both had inherited.

At 6 a.m. on that August 1971 day, cops, FBI agents and the "Thompson Tank"—famous for intimidating civil-rights protesters—rolled down Lewis Street with the goal of serving four warrants, one for a murder suspect they believed had arrived from Detroit and others for misdemeanors. An FBI agent bullhorned for the sleeping radicals, one of them pregnant, to come out in one minute or they would fire. Seventy-five seconds later, they fired teargas into the compound and then gunfire started, JPD records show. The roused inhabitants fired back. Skinner died in the crossfire, and two other officers were injured.

Chokwe Lumumba, who was then 24 and an RNA vice president, wasn't in either house; neither was Obadele, who later served time for conspiracy. But for years, many local whites have considered both of them murderers, as a flyer left during the 2013 campaign on car windshields reminded.

The father mellowed, at least in his degree of heat, over the years, running successfully to serve as Ward 2 councilman in 2009. He had his children in Jackson with his now-deceased and strong-willed wife, Nubia, whom his son now calls the strongest woman he has ever known.

The Lumumba offspring believe in a hardcore, truth-based unity, which is at the heart of the "One City, One Aim" vision—and probably why the younger Lumumba won so handily on primary night in a campaign his sister Rukia Lumumba moved back from New York City to help run.

The majority of the city's electorate, it seems, are now ready to redefine what unity means, electing a young man who scares many people precisely because his very election will mean change, for better or worse.

'The Trump Factor'

The senior Lumumba would have been shocked to see The Clarion-Ledger join this newspaper and the Jackson Advocate in endorsing his son, if not the Ledger's feature the week before painting Lumumba as a cackling radical who travels between Jackson and Harlem with an entourage (probably from Michigan) scheming to get his daddy's Kush plan up and running, in order to steal land and power from white folks and divide it up among themselves.

The Mississippi GOP nearly wigged out on the eve of the primary, sending out a typo-riddled email with a Reagan picture to its mailing list: "Mr. Lumumba—age 34 and the son of the late-Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba—proudly boasts of being supported by the Malcom X (sic) Grassroots Movement, an organization that has stated that it views Lumumba's campaign as being a major part of 'The Big Payback.'" The email added that Lumumba "is someone who associates himself with radical and racially divisive organizations."

Still, this caricature of a scary black radical doesn't seem to faze the presumptive mayor, who grew up hearing the worst about his family and his friends in a state where self-defense and unbridled growth have long been reserved for white people.

The Lumumbas aren't exactly living in a compound waiting to fire on a tank hurling down the street at dawn. Lumumba and his wife, Ebony, and ridiculously cute toddler, Alake, live in a home near their church in northeast Jackson. The presumptive first lady was a Eudora Welty research scholar who is working on her Ph.D at Ole Miss. The Spelman College and Georgia State graduate also teaches at and chairs the English department at Tougaloo College.

The new mayor is more apt to be compared to Drake than Bobby Seale. He equates himself to Maynard Jackson, who became mayor of Atlanta when he was 35, as he did when the older Robert Graham went after him at a April 20 forum.

"You're looking at my wife and my daughter," Lumumba replied. "There are people I employ each and every day whose livelihood depends on me. So to talk about someone's maturity and whether they are capable of leading is just disparaging."

Still, the most notable part is that Jackson voters bought so dramatically into Lumumba's vision. Chism Strategies and Millsaps College analyzed the outcome in the days after the primary, finding several reasons for the surprising landslide.

Undecided voters likely broke for him in the final campaign days. Lumumba had a strong strategy for young voters, including social media (@youth4antar), and he ended with a swell of young, white support his father never got a chance to realize.

"Lumumba's digital ad buy targeted young voters. The results from precincts with sizable portions of younger white voters confirm they had a positive impact," the May 4 Millsaps statement explained.

Millsaps also cited "The Trump Factor: "Lumumba was the most striking contrast to Trump among all candidates, and to the extent undecided voters wanted to express a protest vote against the status quo, Lumumba was that vessel."

In a campaign where challengers were often surly at forums, presenting themselves as the saviors of a city going to hell in the proverbial handbasket, Lumumba offered hope for a unified, high-energy roadmap for those willing to believe. "[T]he consensus is that the Lumumba team was more energetic. Again, history (and a sizable body of research) confirm that other things being equal, voters opt for the more optimistic choice," Millsaps said in its analysis.

This essay contains additional reporting by William H. Kelly III, Arielle Dreher and, in January, Tim Summers Jr. Read more on the city election at jfp.ms/election2017.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID