The flag-draped casket of Stanley Dearman, the former editor of The Neshoba Democrat newspaper in Philadelphia, Miss., is placed before his family, Tuesday, Feb. 28, 2017. Dearman edited the Democrat for 34 years. (Mike Robertson/The Neshoba Democrat, via AP)

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

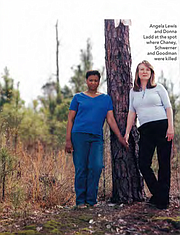

An odd fluke of fate brought me to the patch of dirt where three civil rights workers were murdered in my home county, holding the hand of James Chaney's daughter 40 years after he died there. It was weird to stand on that spot with cameras clicking while local retired editor Stanley Dearman and David Dennis Sr., the man who helped launch Freedom Summer 1964, stood watching. Chaney, 21, of Meridian died on the first day of Freedom Summer, along with Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, of New York City on that spot.

Sheila Weller, a lovable New York writer, had found Angela Chaney Lewis, then living quietly in Meridian 40 years after her daddy's massacre, and me over here in Jackson trying to sustain a newspaper that included real talk and facts on race history in Mississippi and America.

Weller interviewed us both separately about the 1964 executions that put my town on the "bad" map, even as the local Neshoba Democrat ran a large "HOAX" headline across its front page. The state's (white) media helped spread the dumb myth that the men who were willing to die for black freedom would bother to pretend to be missing to piss off racists.

No, the trio's bodies lay under a dam near the fairgrounds for 44 days, put there by cops and others in the KKK willing to do the dirty work of white supremacy. Newspapers around the state, including the Democrat, motivated the racist gangs with negative, sensationalistic reporting about African Americans—telling us incessantly that they were dangerous—thus excusing white attacks on their rights and lives.

At age 14, I first learned about the murders that happened when I was 3. My early desire to be a newspaperwoman was probably instilled as I sat in the library looking at that "HOAX" headline on microfilm. Why did they hide this from me? Why no justice for their deaths?

Stanley Dearman was 31 and a Democrat reporter in 1964; he bought the paper in 1966. He won awards for his journalism, including exposing corruption. But it would be decades before he spoke out loudly about the need for justice for the '64 murders after the state long refused to arrest the men everyone knew committed them.

"It's time for an accounting," Mr. Dearman wrote in 2000. His editorial sugarcoated nothing in a town where people still feared talking about the murders.

"None of this would be an issue if a group of self-appointed saviors of the status quo had not taken it upon themselves to murder three unarmed young men who were arrested on a trumped-up traffic charge and held in jail like caged animals until night fell and they could be intercepted by the Ku Klux Klan," he wrote.

I met Mr. Dearman months later when I came home from Columbia University during spring break 2001 to report on the cold cases that had haunted me for decades. I visited white people considered heroes for doing the right thing when others wouldn't. I asked former Secretary of State Dick Molpus—a Neshoba County native who had apologized to the families of the three men decades later—why he had stayed in the state. To "fight the worthy scrap," he told me—maybe the most inspirational words I had heard until then.

Then I went to see Stanley Dearman. He put me in his car and gave me his frequent tour of the men's final journey on Father's Day 1964: Mount Zion Church to inspect charred ruins; the spot where Deputy Cecil Price stopped them in town; the little jail where they ate their last meal; the hilltop store where the mob waited for them to pass headed back to Meridian after leaving jail; where the mob pulled them over; the execution place on Rock Cut Road; the swamp where the mob dumped their burned car in the Bogue Chitto Creek; the place on Olen Burrage's farm where they bulldozed them under a dam-in-progress.

As Mr. Dearman talked softly about "the three boys" and pointed, he showed me what a newspaper editor ought to be—certainly not a vapid director of stenography who woos happy quotes out of bigots with compliant journalism. He wanted the state flag to change in the vote a few weeks later (it didn't) because he knew just how much spilled blood it represented. He took his responsibility as a newspaperman seriously; our role is not to gloss over history, causes and facts; it is to report and contextualize, to help our communities recover and avoid repeats, to call for action as needed. History matters to journalism and to our lives.

My destiny was set on that spring day listening to Mr. Dearman tell stories, his eyes filled with tears. Three months later, our U-Haul pulled into Jackson, and the next year, this newspaper hit the streets. I know this would not have happened without Stanley Dearman and Dick Molpus showing me what truth-telling looks, and feels, like in my home state. I wanted to fight the "worthy scrap," too, and right here amid the red clay where my family has lived and died. No one said it would be easy, but damn it, journalism is not supposed to be.

I returned to Mr. Dearman's home in June 2005 during the trial of Edgar Ray Killen for orchestrating the 1964 lynch mob. His wife, Carolyn, made me and photographer Kate Medley pimento cheese sandwiches, and we sat in his book-filled study as he played the piano for us. He was thrilled at what was unfolding at the courthouse, where black and mostly white Mississippians would finally choose justice for what happened on Rock Cut Road.

Still, my favorite Stanley Dearman moment was thanks to Sheila Weller. As we all had met in a Meridian hotel in 2004 before driving to the "spot" for the photo shoot, Mr. Dearman and I had casually discussed our frustration that the case had not been re-opened in front of Chaney's daughter. She later told Weller it shocked her. "It was important for me to hear white people voicing that outrage," Angela Chaney Lewis said in Glamour. "I'd never known there was that much concern for justice for my father in the white community."

When I read her words months later, I cried like a baby at the thought that no white person had ever said that to the daughter of an American hero and that Mr. Dearman had, once again, used the power of words to say what had to be said.

He died at age 84 on Feb. 25. I thank him for everything he gave to me and so many others—hope and inspiration.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID