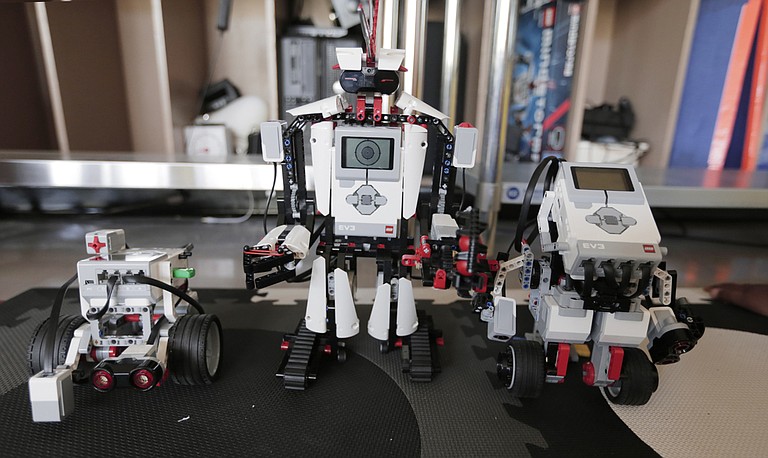

Brown Elementary’s STEAM students build robots and computers after school. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

JACKSON — NunoErin, a design studio based in downtown Jackson, glows with color and light. With its pristine light-up furniture and colorful gaming tables illuminating restaurants, hospitals and hotels all over the world, the company meshes high technology with color and fun. When the pair who runs it, with backgrounds in manufacturing and sculpting, collaborated with Brown Elementary students, they had just finished developing a children's gaming platform, where users can solve problems and play simple games on a touch screen.

Co-founder Erin Hayne says that through collaborations with the students' teachers, they met several times with the Brown students and gave design workshops. "We're interested in giving children a chance to see what their future can be—building confidence, and serving their abilities," she told the Jackson Free Press in an interview.

At Brown Elementary, students have 3D printers and build their own robots and computers. They manipulate software and hardware to complete projects, and their proficiency in science has risen almost 30 percent, Director Darko Sarenac says. Students do all this as part of the STEAM—STEM, with the addition of art (and design) components—curriculum, and have access to a true makerspace in their afterschool program.

It is the first time in Mississippi that public-school students have had access to a so-called "makerspace," also often referred to as a hackerspace, a community workplace stocked with a variety of tools and materials participants can use to create different projects.

Teachers and students alike agree that the makerspace and the after-school technology program provide opportunities for kids at low-income schools such as Brown. But the world of STEM may not be as friendly for them outside the walls of the space they make for themselves.

Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, research associate in the department of physics at the University of Washington, Seattle, says those initial cool opportunities might not be enough. "I would say that having access to such a (maker) space can be really useful for piquing the interest of young people, but they're not sufficient to keep them in the pipeline," she said.

STEM Challenges

Love for math and science usually spurs students to want to study STEM. Money might make the difference, too; in 2014 the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected that STEM careers would grow to more than 9 million between 2012 and 2022. The National Association of Colleges and Employers reported in 2016 that more than half of employers looked to hire college graduates with bachelor's degrees in STEM subjects, and not only that, but also to pay them well—for starting salaries, anyway—at an average ranging from $55,087 to $64,891..

"If you look at the data, black students actually enter universities with high rates of interest of being STEM majors," Prescod-Weinstein said.

"But, they don't end up majoring at the same rate that white students do, despite having an interest in those majors. So it's clear that something's happening during their freshman year of college."

When it comes to keeping black, Latinx and Native students in STEM in higher education, Prescod-Weinstein says representation matters in faculty; those students might be less likely than their white peers to see themselves represented in a diversity of positions. Students also may face social and psychological stress due to racial discrimination.

On a K-12 level, however, the availability of advanced math and science courses through middle school and high school usually encourages students to choose STEM majors.

But schools need to maintain qualified teachers in order to buoy that coursework, which might be difficult for schools in lower-income areas.

But the initial impact on Brown's STEAM students, however, is clear. Ten-year-old Jacqueria is in fifth grade and loves science—there are plenty of things you can find out, she says. Participation in the program is giving her choices for the future that she hadn't considered.

"At first, when I was little, I wanted to be a doctor," she said.

"But when I started taking STEM, I wanted to be a scientist. I just want to build stuff and experiment."

Sierra Mannie is an education reporting fellow at the Jackson Free Press and The Hechinger Report.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID