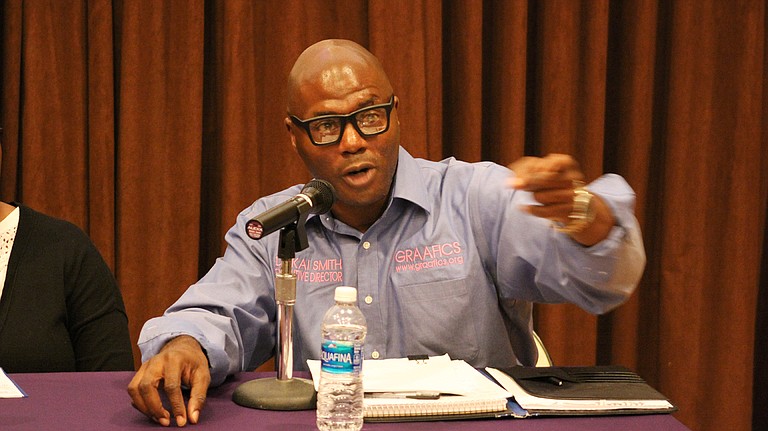

The July 14 JFP Town Hall at Millsaps College with Kai Smith of Harlem opened a safe space for discussions about criminal and juvenile justice reform, alternative programs and community involvement in keeping children out of the system. Photo courtesy Kelsee Ford

Friday, July 15, 2016

JACKSON — The room was nearly packed on July 14 at Millsaps College as concerned members of the community gathered for a town-hall meeting on preventing violence, gang interruption, and alternatives to juvenile detention and juvenile justice presented by the Jackson Free Press and the Solutions Journalism Network.

The panel for the evening's discussion included Dr. Kai Smith, the executive director for GRAAFICS (Gang Diversion, Reentry And Absent Fathers Intervention Centers) in New York City; Cassio Batteast, director of M.A.N. U.P. (Mississippi Action Network for Uplifting Promise) in Jackson; Donna Ladd, editor-in-chief of the Jackson Free Press, as well as this reporter.

The conversation revolved heavily around children who have been in the juvenile-justice system and a better way to prevent them from committing worse crime. Smith urged citizens to take the time to listen to young people, to take action, and invest time and money back into programs that already exists that can help provide "wrap-around services" that can put them on a different path and interrupt cycles of violence.

The BOTEC report, a recent study on the City of Jackson's justice system, came up often. The report predicted that, without proper intervention, the Jackson Police Department or the Hinds County Sheriff's office will arrest 5 percent of children in Jackson Public Schools at some point. The study also found that only 225 young people in JPS are at risk of committing violent crime at some point, and suggested ways to redirect them from cleaning up abandoned houses, or "bandos," to mentoring, to criminal-justice alternative programs.

Batteast mentioned the policies that sometimes leads children into the situations they're in, such as "zero tolerance" discipline that often "has zero tolerance for the people who often need all the tolerance in the world" in order to land in a better place. The strict discipline policies, which do not allow discretion, place the same level of consequences on lesser crimes as violent offenses. The policy is often directed toward young people growing up in poverty, which leads to both child hunger and propensity for crime, as well as with a lack of parental involvement, often for the same reasons. These problems usually cross over into educational time, where children who are unable to focus in school, lash out at teachers or classmates, or don't show up to class and end up in juvenile detention instead of being offered services to alleviate their problems.

Ladd pointed out the voluminous research that shows that the more times a young person has contact with the criminal-justice system, the more likely he or she is to stay on a criminal trajectory. "It's irrefutable that the more times a young person has contact with the criminal-justice system, the more like they are to commit a worse crime," Ladd said.

"I think that if we can talk about these wrap-around services, like Kai mentioned, we can get to a lot of the young people before they get into something worse, something other than police intervention, but we've all got to put our heads together to make sure that there are no holes in that net."

"Incarceration is not the solution. It's not the answer. It's part of a solution, but it's not the solution," Smith said.

However, he is not against all incarceration and pushes back on the phrase "over-incarceration" as a vague phrase that means very little, much like the phrase "community policing." In fact, the six-time felon who spent 16 years behind bars in three states, said prison was what put him on the right path, and was where he started writing the curriculum he now uses in programs in schools in New York City, as well as Riker's Island, the infamous jail there.

"If I didn't go jail 16 years ago, I'd be dead now," Smith said.

Smith, who has been in Jackson since Monday, has been speaking to public leaders, everyday citizens and young people about his tough-love vision of breaking the cycle, and "changing the narrative" that is attached to young people of color.

"If I can do it, you can do it," he told the town-hall audience. He also challenged listeners to stop looking at Jackson crime as something that they cannot change. He has learned here that too many "Jackson folk are looking at the glass as half-empty," he said, "instead of half-full." He challenged them to do what is needed "for these kids," pointing to a number of young people in the audience from the Mississippi Youth Media Project. He said each audience must figure out a way they can help one of the 225 young people that BOTEC warned is at the highest risk of violent crime.

Smith raised some eyebrows in the room when he answered a question about police violence and the Black Lives Matter movement by saying that it is more important what happens after a march to help young people lift themselves up and change the narrative about their lives.

View the Facebook Live video of the town-hall meeting here and visit Smith's website at graafics.org or on Facebook. Read the JFP's ongoing "Preventing Violence" series at jfp.ms/preventingviolence.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID