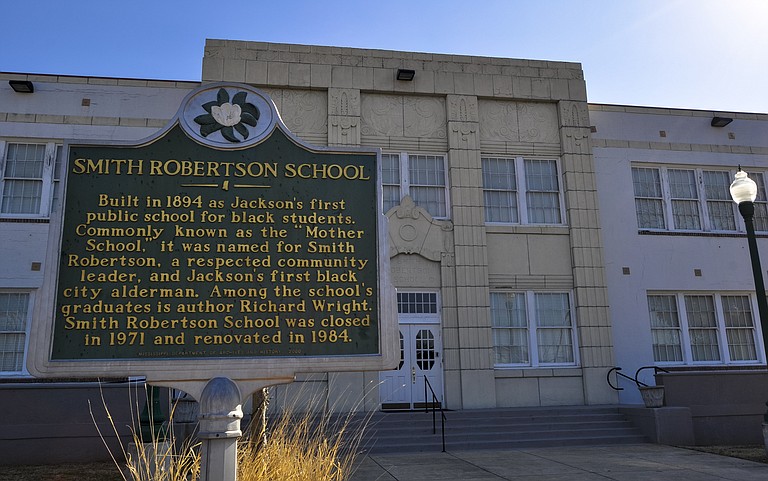

The Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center tries to educate the public on the culture and history of those with African heritage. Photo by Trip Burns.

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

From the outside, one can't possibly see the beautiful and tragic history that the two-story gray building on Bloom Street holds. Built in 1894 as the first public school for African Americans in Jackson, the school-turned-museum not only shares the experiences of black people but is a vital part of the state's history as well. Today, it tells the history and achievements of African American Mississippians as the Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center.

Smith Robertson was a former slave who migrated from Fayette, Ala., to Mississippi after the Civil War. He became a businessman and, eventually, the first African American alderman for the City of Jackson. The mayor and the board of aldermen appointed Robertson to the Board of Trustees for black students in 1879. The school, which opened in 1894, was named after Robertson. It remained a learning center until 1970, when Mississippi's desegregation of public schools finally began.

In 1983, a group of people united to turn the now-dilapidated "Mother School" into a museum, dedicated to fulfilling its purpose to "educate the public on the historical experience and cultural expressions of people of African descent," as its mission statement reads. The Smith Robertson Museum is one of the leading museums in Mississippi that tell the complete history of African Americans in the state. Notably, CNN recognized the museum in "50 States, 50 Spots for 2014."

"We know that any people who don't know their history—or aren't privileged to know their history—tend to repeat it," says Charlene Thompson, one of Smith Robertson's curators and its researcher. "It's important we share this history each and every day."

The museum's first floor features the David Taylor Gallery. Most recently, the gallery held the temporary exhibit, "Jackson State University's Department of Art Faculty Show," featuring the work of Charles Carraway, Chung-Fan Chang, Mark Geil, Hyun Chong Kim, Chalmers Mayers, Jimmy Mumford, Yumi Park, Ken-yatta Stewart (who is also a Smith Robertson curator and the museum's designer) and Dorothy Whitley. Each piece of art shows the artist's individuality, and, collectively, they display a unity of talents. The artists communicate their personal passions through a variety of materials, from archival pigment prints of ancient South American monuments to textured art work of West African drums.

The Folk Art Hall holds the Ferris-Freeman Quilt Collection. Each quilt, through its intricate patterns and colors, holds a message. The flying geese quilt, for example, once directed slaves to follow the geese as they migrated north. The Contemporary Art Hall features oil and acrylic paintings that express the artists' views on black life. Betty LaDuke's art work has an African theme, for example, whereas Kenyatta Stewart's commissioned piece "I Am" connects Senegalese and French roots.

On the second floor of the museum are the permanent exhibits such as "From Africa to Mississippi," "Field to Factory: Afro-American Migration, 1915-1940" and an interactive "house" about civil-rights activist Medgar Evers. In the exhibit "Those Who Stayed," you learn, in chronological order, about the journey Africans took from their homeland to the Americas. "From Africa to Mississippi" has artifacts, sculptures and even a mock slave ship that allows patrons to visualize how life was for people of color years ago.

The voices Charles and Elizabeth Evers, Medgar's older brother and sister, narrate "The Retrospective Life of Medgar Evers." The exhibition of the civil-rights activist's life is set up to inspire those who walk through the screen door. Beyond the front-porch setting is a room full of facts about Medgar, from his youthful adventures to his dedication to the cause of freedom for all. The interactive room challenges visitors to think about their personal experiences and values.

"(Smith Robertson Museum) endeavors to make history more visible and more readable," Thompson says.

But Medgar isn't the only figure the museum honors. Just beyond the museum's store is a display that chronicles Richard Wright's life work and has the terracotta figure "Black Boy" by Harold Dorsey. One of Mississippi's renowned authors, Wright graduated from the school in 1925. His classic autobiography, "Black Boy," and the novel "Native Son" have similar themes of black life in America. Wright's haiku is on the mural beyond the gated parking lot: "This is where I am: summer sunset, loneliness purple meeting red."

This year, which marks the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, there isn't a better time to visit or revisit one of Jackson's oldest historic buildings. See the JSU Art Faculty Exhibit before it leaves Dec. 31, as well as the permanent exhibits. And, in February, see the "Mississippi Slave Narrative" exhibit during Black History Month.

The Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center is located at 528 Bloom St. Hours are Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Admissions is $4.50 for adults, $3 for senior citizens ages 62 and up and $1.50 for children ages 17 and under. For more information, call 601-960-1457 or visit city.jackson.ms.us.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID