Wednesday, May 10, 2006

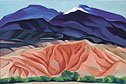

If you are at all familiar with Georgia O'Keeffe's work, you've seen at least one meticulously painted flower, cow skull or landscape. A close look at O'Keeffe's paintings, however, causes some to question if there's more to them than meets the eye. The Mississippi Museum of Art is housing the exhibit, "Georgia O'Keeffe: Color and Conservation," to allow you the opportunity to answer for yourself. The display had such an impact on me that not only have I seen it multiple times, but it prompted me to learn more about the artist and her life.

O'Keeffe, born well before the time when it was common for women to be educated, was a trained artist. After attending a number of schools, she became an art instructor. During this time, she created a series of charcoal drawings that set her art, career and life onto a new course. The pieces were responsible for introducing O'Keeffe to Alfred Stieglitz, a gallery owner. Upon seeing some of her works, Stieglitz exclaimed, "At last, a woman on paper!"

Stieglitz was so impressed with this woman's work, in fact, he encouraged her to leave the teaching profession and promised her financial provision if she did so. And so she did. During her time in New York, O'Keeffe painted architectural pictures, but it wasn't until she visited the Stieglitz family summer home in Lake George, N.Y., that she began to produce the paintings that she would become famous for.

The expansive and intense images of flowers and, some years later, bones from the desert of New Mexico, would soon become the object of much discussion. In "Corn No. 2," for example, the artist all but forces us to look at the natural beauty of an ear of corn. From the intoxicatingly bold colors to the paler shades that gently fade, the artist wants the viewing audience to concentrate on something easily missed with the blink of an eye. So, she freeze-frames the image, thereby stripping away its banality.

Because of the intimate relationship the artist initiates between the viewer and the subject of the painting, her works made her a target for criticism. While O'Keeffe did all she could to distance herself from critics by eventually spending almost all of her time in relative solitude in New Mexico, it wasn't enough to keep her works from being dissected. In 1946, Clement Greenberg was quoted in a review as having said that "the greatest part of her work adds up to little more than tinted photography. (And her work) has less to do with art than with private worship and the embellishment of private fetishes with secret arbitrary meanings."

Of course, most people familiar with the artist have heard that her works were suggestive, but this is in direct contrast to what the artist herself said about her paintings. She would often become frustrated with the interpretations her abstractions generated, believing critics married their own fixations to her works. O'Keeffe explained that she only painted what others do not have time to see for themselves.

Although I have been told about the artistic intentions of her work, I cannot ignore the other interpretations that point out its suggestive nature. Such elucidations of her compositions led her to become iconic in feminism. The elegance, sensuality and resoluteness that are femininity are incontestable even to the untrained artistic eye. And while many ideas in feminism remained unexpressed until the 1970s, feminist art has confronted questions like "How is a woman's gaze different from a man's?" and "What constitutes obscenity and pornography?" O'Keeffe's oeuvre demands that every viewer face these questions.

The Mississippi Museum of Art's exhibit not only emphasizes the color used in the artist's work, but also the painstaking methods she used to conserve her work. O'Keeffe wanted her works to last. And they have. Not only have they lasted in the sense of preservation of original color and surface quality, but also in their relevance to the generations that have followed. We can see the integrity of O'Keeffe's work through her spiritual connection to the objects and landscapes she painted. Controversy over her "flowers" will abide. She said one thing; others say differently. But good O'Keeffe's paintings suggest multiple valid interpretations worth debating endlessly. That is the essence of good art, as I hope even Georgia would agree.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 84531

- Comment

i think Pink Floyd hinted at these same suggestions in using some of her works in "The Wall". I think its split in half either you think they do or they don't. I say yes

- Author

- *SuperStar*

- Date

- 2006-05-12T16:45:47-06:00

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID